Sherman Alexie

The Lone Ranger and Tonto Fistfight in Heaven

For Bob, Dick, Mark, and Ron

For Adrian, Joy, Leslie, Simon,

and all those Native writers

whose words and music

have made mine possible

Theres a little bit of magic in everything

and then some loss to even things out.

Lou Reed

I listen to the gunfire we cannot hear, and begin

this journey with the light of knowing

the root of my own furious love.

Joy Harjo

PROLOGUE:AN EMAIL EXCHANGE BETWEEN JESS WALTER AND SHERMAN ALEXIE

From: Sherman Alexie

To: Jess Walter

Sent: Thursday, June 20

Subject: Twentieth Anniversary Lone Ranger and Tonto

SA: So Ive been trying to write the intro to the 20th anniversary edition, but it feels too self-congratulatory, so do you want to have an email exchange about it and use that as the intro?

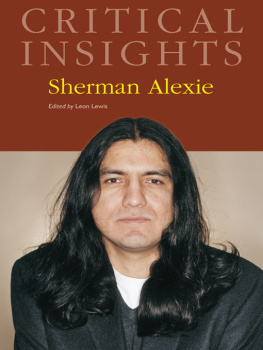

JW:The Lone Ranger and Tonto Fistfight in Heaven is 20!?! Your email sent me scurrying to my signed copy. I looked at the jacket photo and there you are, with the greatest Breakfast Club pro-wrestling warrior mullet of all time.

SA: The rez mullet! I also find my former haircut amusing in stylistic terms. Its embarrassing now. But theres always been a conscious and subconscious classist/racist edge to mullet jokes, especially when it comes to white guys with mullets. If one means to tell a racist/classist joke, then make it a good one, but I dont actually think that many folks realize the cultural importance of the mullet in Native American warrior history. Take a look at Chief Joseph.

Unravel those braids, my friend, and youve got a legendary mullet, comparable to mine. The contemporary motto for the mullet wearer is business in front, party in the back, but the Indian mullet warrior motto was I dont want my hair to get in my eyes as Im kicking your ass. The Indian mullet motto, coincidentally or not, is the same as the motto for hockey mullet wearers. Somebody needs to do a study

Looking at my hair through a slightly more serious lens, I think I wore such an exaggerated mullet as a means of aggressively declaring my Indian identity. And my class identity. When The Lone Ranger was published, I was being fted by the publishing world while I was back living on the rez, after college. I was called one of the major lyric voices of our time but at the same time I was sleeping in a U.S. Army surplus bed in the unfinished basement bedroom in my familys government-built house.

The contrast between my literary life and my real life was epic. Scary. Even dangerous. And it felt epic, scary, and dangerous for many years.

My mullet was an insecurity shield. My mullet was an ethnic hatchet. My mullet was an arrow on fire.

My mullet said to the literary world, Hello, you privileged prep-school assholes, Im here to steal your thunder, lightning, and book sales.

JW: Yes, undoubtedly: Chief Josephs business in front carries more power and meaning than say, Brian Bosworths. (My own unfortunate mullet included a braided rattail just in case I wasnt white trash enough.) And in your author photo from that time there is a fierce, steady engagement in your eyes that reflects exactly that quality in the book you are drawn in by the humor, the sorrow, and the anger over injustice, the steady and unblinking cost of admission. I remember so clearly the reviews you were getting, and especially that phrase from the New York Times Book Reviews cover story on The Business of Fancydancingone of the major lyric voices of our timebut I couldnt have comprehended the pressure that such praise brings, especially the identity component of it, and so early in your writing life. To follow those reviews with a book like Lone Ranger, is, frankly, kind of fucking remarkable. The book won the PEN/Hemingway Award for best first fiction and garnered even more praise, but it must have felt like even more weight; every writer dreams of stunning and dazzling, but The Chicago Tribune writing, The Lone Ranger and Tonto Fistfight in Heaven is for the American Indian what Richard Wrights Native Son was for the black American in 1940. What does a 26-year-old do with that?

The pressure of straddling two worlds comes through in Lone Ranger. In A Good Story, the gap is represented by the sweetest bit of postmodernist breaking of the fourth wall, in which you, the author, seem to be lying on the couch and your mother pleads with you to write a story about something good.

Another example of the disparate worlds youve suddenly found yourself straddling is one of my all-time-favorite stories, The Trial of Thomas Builds-the-Fire, which begins with a wonderfully apt epigraph from Kafkas The Trial: Someone must have been telling lies about Joseph K., for without having done anything wrong he was arrested one fine morning. Your name, your boys name: Joseph. You almost seem to be staking out territory on the literary side of that divide, and having to defend yourself to both sides. That story also moves toward something I see in your work a brotherhood in class, Thomas on the bus to prison with four African men, one Chicano, and a white man from the smallest town in the state, delivering them to a new kind of reservation, barrio, ghetto, logging-town tin shack.

SA: And now I remember a New Yorker magazine party early in my career when I stepped out of a penthouse apartment elevator and saw Stephen King and Salman Rushdie hugging each other. What does a rez boy do with that visual information?

Oh boy, do I still feel like a class warrior in the literary world. In the whole world, really. These stories are drenched in poverty and helplessness.

Weve talked about this a few times. I often make the joke that your trailer park poverty makes my rez poverty look good.

But thats an overlooked part of these stories, I think. I grew up in the tribe called the Rural Poor, as did you, and I dont think folks think of us that way. I grew up in wheat fields. I grew up climbing to the tops of pine trees. I grew up angry and ready to punch a rich guy in the ear.

So, yeah, realism is my thing in this book. Autobiography, too. Not an autobiography of details but an autobiography of the soul.

One thing: I wrote this book in the middle of a decade-long effort to believe in God. So its curious to see the uncynical God hunger in the boy I was.

JW: Oh man! Thats a little more high-powered hug than you and I hugging at the LA Times Book Festival in 1996. I still remember, you said, What are you doing here? Then you introduced me to Helen Fielding, of all people. This is Jess Walter, the second-best writer from Stevens County, Washington. And we both laughed, because you and I knew that I was the ONLY other writer from Stevens County, Washington.

To my shame now, I grew up embarrassed about being bluecollar, a first-generation college student, a 19-year-old father. We usually think of passing in terms of race, but people try to pass as another class, too. I did that.

You, however, seemed to know at least as a writer to claim class as a subject, that literature belongs to the poor shits, too. Your stories are sneaky that way: They confront readers on that level; theres a quiet insistence that THIS WORLD is as rich a literary world as London or New York, that Benjamin Lake can be as profound a place as Walden Pond, that Tshimikain Creek can have every bit as much literary resonance as the Thames.

But place and class are only part of the story. Many people tell me that they had no picture of contemporary reservation life, or even urban Indian life, until reading