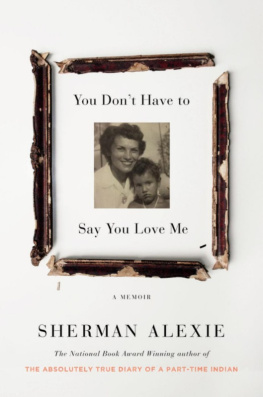

Copyright 2017 by FallsApart Productions, Inc.

Cover design by Julianna Lee; photograph (frame) by Slaven Gabric/Millennium Images, UK

Author photograph by Lee Towndrow

Cover copyright 2017 Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Little, Brown and Company is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Little, Brown name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

I N 1972 OR 1973, or maybe in 1974, my mother and father hosted a dangerous New Years Eve party at our home in Wellpinit, Washington, on the Spokane Indian Reservation.

We lived in a two-story housethe first floor was a doorless daylight basement while the elevated second floor had front and back doors accessible by fourteen-step staircases. The house was constructed by our tribe using grant money from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, more tersely known as HUD. Our family HUD house was new but only half finished when we moved in and remains unfinished, and illogically designed, over forty years later. It was worth $25,000 when it was built, and I think its probably worth about the same now. I dont speak my tribal language, but Im positive there are no Spokane Indian words for real estate appreciation.

The top floor of our HUD house contains a tiny bathroom with an unusually narrow door and a small windowless kitchen, both included as afterthoughts in deadline sketches hurriedly drawn by a tribal secretary who had no architectural education.

I didnt grow up in a dream house. I lived in a wooden improvisation.

On the top floor with the kitchen and bathroom, there is also a minuscule bedroom that was shared by my little sisters, identical twins, during childhood. My sisters, Kim and Arlene, never married and nearly fifty years old now, have never lived more than one mile apart, so perhaps they cannot escape their twinly proximity.

Also on the top floor of our HUD house is the master bedroom, where my late father slept alone, and a disproportionately large living room, where my late mother slept on a couch.

My late father, Sherman Alexie, Sr., was a Coeur dAlene Indian. He was physically graceful and strong, adept at ballroom waltzes, powwow dancing, and basketball. And always smelled of the smoke of one good cigar intermingled with dozens of cheap stogies. As a teenager, he began to resemble the actor Charles Bronson, and that resemblance only increased with age. Introverted, depressed, he spent most of his time solving crossword puzzles while watching TV.

My late mother, Lillian Alexie, crafted legendary quilts and was one of the last fluent speakers of our tribal language. She was small, just under five feet tall when she died. And she was so beautiful and verbose and brilliant she could have played a fictional version of herself in a screwball Hollywood comedy if Hollywood had ever bothered to cast real Indians as fictional Indians.

I dont know if my parents romantically loved each other. I am positive they platonically loved each other very much.

My mother and father slept separately from the time we moved into that HUD house in the early 1970s until his death from alcoholic kidney failure, in 2003. And then my mother continued to sleep alone on a living room couchon a series of living room couchesuntil her death, in 2015. My parents were not a physically affectionate couple. I never saw, heard, or sensed any evidenceother than the existence of us childrenthat my mother and father had sex at any point during their marriage. If forced to guess at the number of times my parents had been naked and damp together, I would probably say, Well, they conceived four children together, so lets say they had sex three times for keepsthe twins only count for oneand four times for kicks.

My big brother, Arnold, and I each had our own mostly finished basement bedrooms. But he spent much of his time living and traveling with a family of cousins like they were surrogates for his parents and siblings. I love my brother, but he sometimes felt like a stranger in those early years, and I imagine he might say the same about me in our later years. Never married, but in a decade-long relationship with a white woman, he is loud and hilarious and universally beloved in our tribe.

The furnace and laundry rooms, also in the basement, are cement-floored with bare wood stud walls. Dug five feet into the ground, our basement flooded with every serious rainstorm and has smelled of mold, and subsequent disinfectant fluids, from the beginning of time.

My little brother, James, who is also our second cousin, was adopted by my parents when he was a toddler. Fifteen years younger than me, he would eventually take over my bedroom after I went away to college. He was so starved when we got him that he would devour any food or drink in his vicinity, including other peoples meals. While we were distracted, he once drank my fathers sixty-four-ounce Big Gulp of Diet Pepsi in one long pull. He was only three years old. We thought it was funny. We didnt ponder why a kid would come to us so very thirsty.

James was only five years old when I moved away from the reservation. So I think I have been more like his absent uncle than his big brother.

Smart and handsome and thin and also married to a white woman, James has a masters degree in business.

Ah, my little brother is my favorite capitalist.

But that inexpertly constructed HUD house was still a spectacular and vital mansion compared to the nineteenth-century one-bedroom house where I spent most of the first seven years of my life. That ancient reservation house didnt have indoor plumbing or electricity when my parents, siblings, and I first moved in, along with an ever-changing group of friends, cousins, grandparents, aunts, and uncles.

I most vividly remember my half sister, Mary. She was thirteen years older than me and seemed more like a maternal figure than a sibling. Even more beautiful than our gorgeous mother, Mary was a charming and random presence in my life. She was profane and silly and dressed like a hippie white girl mimicking a radical Indian. In later years, I would learn that Marys randomness and charmand her eventual death in a house firewere fueled by her drug and alcohol addictions. I didnt yet know that romantic heroesfamous and notare usually aimless nomads in disguise. Marys father lived in Montana, on the Flathead Indian Reservation, so she sometimes lived with him and sometimes lived with us and sometimes shacked up with Indian men who reeked of marijuana and beer or with white men who looked like roadies for Led Zeppelin. A mother at fifteen, Mary gave her baby, my niece, to our aunt Inez to raise. My niece is only a few years younger than me, and I still dont understand why my mother didnt take her into our home. My parents raised one of our cousins as a son, and my sisters would eventually raise another cousin as a daughter. So why didnt our niece become our sister? I never asked my parents those questions. But, in writing the first draft of this very paragraph, I realized for the first time that my father, so passive in nearly all ways, might have said no to raising a granddaughter who was not his biological relative. I feel terrible for considering this possibility. Could my father have done such a thing? Could he have been such an alpha lion? I dont know. I dont think so. I hope not. So why didnt my mother raise her granddaughter? I doubt that Ill ever be able to answer that question. There are family mysteries I cannot solve. There are family mysteries I am unwilling to solve.