Copyright Frank Bongiorno 2015. First published 2012.

Frank Bongiorno asserts his right to be known as the author of this work.

All Rights Reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior consent of the publishers.

The National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry (for print edition):

The sex lives of Australians : a history / Frank Bongiorno.

2nd edition.

Australians--Sexual behavior--History. Australians--Sexual behavior--Political aspects. Social change--Australia--History. Australians--Social life and customs--History.

Every effort has been made to contact the copyright holders of material in this book. However, where an omission has occurred, the publisher will gladly include acknowledgement in any future edition.

Foreword

The Hon. Michael Kirby AC CMG*

* Justice of the High Court of Australia (19962009), President of the International Commission of Jurists (199598); Laureate of the UNESCO Prize for Human Rights Education (1998); Australian Human Rights Medal (1991).

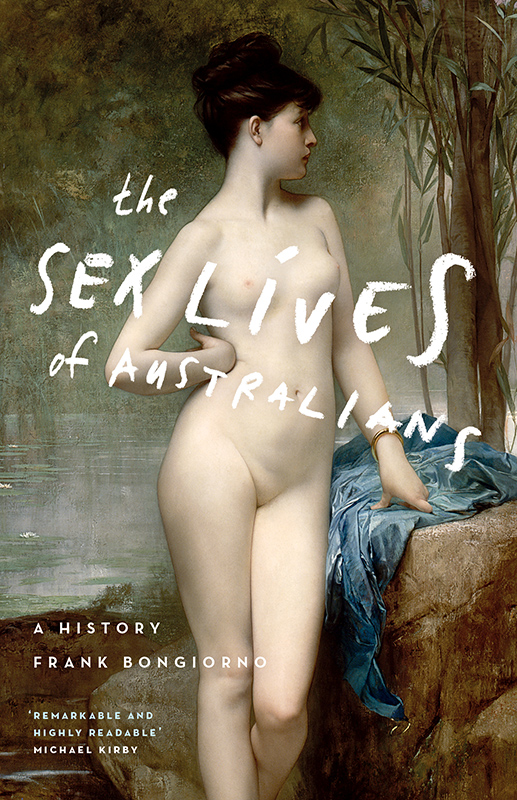

This remarkable and highly readable book offers a cornucopia of sexual tales from history. It holds up a mirror to Australian society and describes the sexual lives of its people from the first penal settlement in 1788 to the present times.

The book starts with stories of the sex-deprived convicts, mostly men, arriving in the Antipodean world. The advent of the first boatloads of disempowered women is recounted, as is the very vulnerable condition of the Indigenous people and the so-called half-castes that sprang from sexual unions with them. It proceeds through the early colonial age of repression, of harsh laws, of capital crimes and the cult of mateship. Captain Moonlite, the bushranger, strides boldly across the stage with his male lover. He and the Kelly Gang contributed to a panic over sodomites: the moral enemies of Australian society. The opening of the Victorian age sees reflections in the Australian colonies of many of the controversies that beset England and America at the same time: scandals in high places; hypocrisy in public and private conduct; patriarchal attitudes to ladies; harsh sexual censorship; backyard abortions; the early controversial ventures into birth control; the plight of fallen women; and the ever-present quest for social, racial and religious purity.

Even masturbation deeply disturbed many of the leaders of Victorian society. Spilling of the seed was regarded as a serious sin and it was a topic for endless debate and solemn instruction, mostly addressed to the young.

By the end of the nineteenth century, sadomasochism had put in an appearance, including by the gifted composer Percy Grainger. So had cases of cross-dressing. Venereal disease was literally on many peoples lips. And with the start of World War I, a large cohort of young Australian men ventured overseas to discover, for the first time, the brothels of Cairo and Paris, before they were marched off to Gallipoli and the Somme, to die in the empires battles. Our soldiers and their cousins from New Zealand proved shockingly sexual for the stern British commanders. Merrily they sang the song, Howre they going to keep him down on the farm, after hes seen Paree? Sexual internationalism had well and truly arrived.

The postwar era and the Great Depression brought the return of countless controversies in Australia over nudity, erotica, supposed clitoral nymphomania and that old recurring anxiety over masturbation.

But soon, the very existence of the nation was in danger. World War II brought factory girls and many young men freed from the suburbs and farms, facing the possibility of death and determined to savour the joys of life, whilst they had it. The clientele for sex in Australia included some of the Yankee soldiers, a number of them black: exposing Australian women to the unaccustomed attractions of racial variation, not often seen in the era of White Australia.

When the Yanks went home, wartime austerity gave way to cautious national prosperity in the 50s and 60s. Heavy petting, car sex, bodgies and widgies, rock n roll and other dastardly threats made their appearance. Lady Chatterley and Billy Graham take their bows in this Act of the drama, although not necessarily together.

And, as if this were not enough, the era of permissiveness gave way to a sexual revolution. The contraceptive pill saw women liberated from pregnancy. Naturally, religious leaders denounced the consequences, declaring them to be an end to civilisation. Their worst fears seemed to be realised, not only by the promiscuity of healthy young heterosexual Australians shamelessly living in sin, but also by an increasing cohort of gay advocates, after Dennis Altman, who outrageously refused to be ashamed of their perversion. Increasingly, this queer minority even began demanding equal legal rights including (horrors) the right to marriage equality and civil recognition and acceptance of their intimate long-term relationships.

Although, by the current age, the denunciation of masturbation appears, at last, to have abated in the litany of Australias national anxieties, new sources of stigma and discrimination appeared in the past twenty years to agitate the national psyche.

Just when sexual freedom was tasted for the first time, including among the previously demonised sexual minorities, a strange new retrovirus appeared, apparently out of Africa, to sweep the world. Cunningly it chose penetrative sexual intercourse as its major portal of entry. Whereas in Africa and Asia, the major impact of this virus was on heterosexuals, in Australia, as in other Western societies, the newly liberated communities of gay men felt the heaviest burden. With the virus came a groundswell of new fear and loathing.

To prove that attitudes to sexual activity are cyclical, and partly political, some Australian politians, taking their lead from America, saw votes to be had in whipping up new hostility. A huge media-driven campaign of fear was raised against paedophiles, often causing confusion in the public perception of homosexuals. Continuous campaigns were waged to tap religion-fuelled fears of relationship recognition for sexual minorities. The success of such campaigns can be measured by their impact on recent elections in Australia, as in the United States. Fear, whether on the ground of gender, race or sexuality, is always a potent weapon for demagogues.

The social value of this book is that it helps us to understand the debates and controversies that arise for contemporary Australians, by recognising their links to the same forces that had to be faced and overcome in earlier times. By knowing more about our past in this regard, Australians may become wiser and more accepting of sexual differences at present and in the future. And less willing to jump on the bandwagons so regularly rolled out by politicians and the media when the electoral cycle makes its recurrent appearances. As well, this book reveals a large unwritten story of the burden that repressive laws and attitudes have placed on millions of human beings. They have been cast into a well of loneliness by an enforced celibacy, often advocated by religious leaders. Yet now we have reached a time where the joy and fulfilment of a happy sexual life is often possible. And increasing millions will demand it, for it is central to a happy life, good health and personal fulfilment.