The general series of the

Miegunyah Volumes

was made possible by the

Miegunyah Fund

established by bequests

under the wills of

Sir Russell and Lady Grimwade.

Miegunyah was the home of

Mab and Russell Grimwade

from 1911 to 1955.

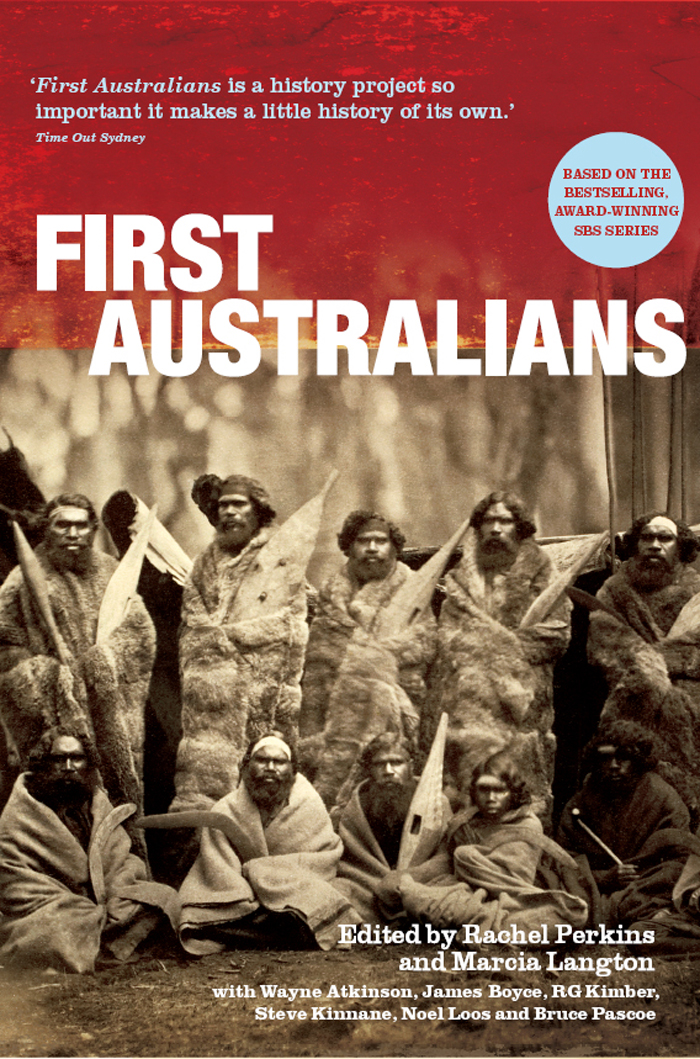

FIRST AUSTRALIANS

FIRST AUSTRALIANS

EDITED BY RACHEL PERKINS AND MARCIA LANGTON

with Wayne Atkinson, James Boyce, RG Kimber, Steve Kinnane, Noel Loos and Bruce Pascoe

CONTENTS

MARCIA LANGTON

MARCIA LANGTON

JAMES BOYCE

BRUCE PASCOE

RG KIMBER

STEVE KINNANE

WAYNE ATKINSON

MARCIA LANGTON AND NOEL LOOS

MARCIA LANGTON

PROLOGUE

Marcia Langton

Historians tell stories about the past and, among other things, about people, ideas, institutions and, importantly, nations. Most of us were first introduced to the idea of history at school. In most Australian schools that my generation attended, Aborigines were represented almost universally as animal-like, cunning and treacherousas enemies of the nationin what passed for history lessons, learnt by rote as a set of dates, in the 1950s and 1960s. Teachers would mention a few exceptional Aboriginal people, such as Jackey Jackey, the famous native servant and guide who remained loyal to the explorer Edmund Kennedy. In 1848 Edmund Kennedys expedition through Cape York Peninsula met with fatal results: Kennedy and most of his team were killed by Aboriginal men in the far north of the peninsula, Jackey Jackey being one of two survivors. Jackey Jackeys account of the incident was transcribed and be came a famous pamphlet, and the man himself a strange hero.

As a child growing up in Queensland, I found these stories bizarre. Occasionally, there was something of interest, but the overwhelming tone was one of turgid prose about utterly boring subjects such as the discovery of rivers, flocks of sheep, wheat crops, stump-jump ploughs, railway gauges, Governor This and Governor That, and Australia Felix. The occasional Aboriginal characters represented bore no resemblance to the people I knew and had grown up with. Gradually, there was a dawning realisation that I was seen by my teacher and classmates as one of those Aborigines. History was for me a terrible burden because it was in this class that I learnt that people like me were hated, and that the only stories told about us provided a steady stock of evidence about our supposedly shockingly violent tendencies, savagery and, most importantly, our innate tendency to steal and pilfer.

In the past half century, as a new generation of historians has interpreted the records, a dazzling view of Australian life has emerged. Instead of the drudges who peopled the pages of the old books, convicts, women, children, African-American slaves, adventurous European aristocrats, artists, con-men, bushrangers and thousands of Indigenous people have assumed more detailed, nuanced and intriguing personas, and their endeav ours have become better understood. The ridiculous and audacious, as well as the common or garden, activities of ordinary and extraordinary people have replaced the monotonous tales of the March of Civilisation.

Only a handful of historians, mostly amateurs, persist in vilifying all the original inhabitants of this continent and their descendants. Despite their less than rigorous skills in the discipline, their few works have an enormous influence, principally because they propose racially slanderous views that most educated people would reject, but that remain attractive to those who prefer to imagine the Australia of the old school books, the Progress of the White Man: courageous white explorers in the colonies, staking out the wilderness for God-fearing farmers amid the demise of the backward natives according to the laws of natural selection. That such views remain enormously popular and attractive is one of the reasons for this book. We have a high regard for the importance of the history of Australia to all of the people who call this place home in the twenty-first century.

Without history, how would we believe in the idea of Australia? The story of the people who have lived here is not a straight forward one, however. Far too many Australian history books have demeaned the Indigenous people and society that the British encountered, so the purpose of the First Australians pro ject has been to understand the part played by Indigenous people in the events that caught our imagination. In a modern Australia, the past cannot be exploited simply for triumphalist purposes, to attribute cause and effect to more palatable theories, to elevate the colonial pioneers over the first peoplesthe squatters and settlers over the traditional owners of landwithout the risk of concocting an incredible and insubstantial mythol ogy. Fortunately, there are both primary and secondary documents that give due weight to the Indigenous part in the story. These have enabled us to depict in great detail some of the Indigenous people who were so often ignored in the making of Australian history.

History is a world of alternatives. Readers of the archives will each follow their own trail through the pages of journals, diaries, past accounts and images, perhaps lured by a special char acter or intrigued by a particular event.

First Australians begins appropriately with the First Fleet, whose commander, Lieutenant Arthur Phillip, encountered the peoples of the Sydney region. The harbour was named Port Jackson by Lieutenant James Cook, although he did not sail through the heads but went on north after his few days at Botany Bay. Phillips journal, and those of his officers, surgeon, scientists, artists and visitors, tell a complex story of their relationships with the clans who called the harbours shores their home. Friendships developed between Phillips contingent and the local people and, although they were caught up in the imperial mission of con quest, their journals reveal their sense of wonder, practical cour age and wit in extraordinary circumstances. We story tellers have been charmed by their sentiments, and sometimes amused and intrigued by their wry turns of phrase.

Bennelong, particularly, captures the imagination, and while our understanding of his life is filtered through the views of very eighteenth-century English men as well as our own, nevertheless his light shines through the texts and images. The tales of sex, violence, hunger and desperation that surround Bennelong and his people are horrifying. Phillip and his companions became involved in this world and left us textual glimpses of a society that collapsed soon after these events transpired. Our story is scored with the troubling implications of hindsight: Bennelongs fate and that of his people were tragic, but for a few years after 1788 the events at Port Jackson and surrounds were extraordinary. We have tried to hold on to the substance of the affairs represented by the historical records; to avoid unnecessarily transposing our present sensitivities into the narrative. Yet it has been impossible to ignore the strangeness of the ambitions, skills, intellect and emo tions of the people who wrote the texts. The story is as tangled as any epic might be. Values, morality, the role of the gods, the hand of fate: we thought it best to let them play their role.