Dedicated to my friend

Jamie Ian Lyden

30 July 1981 17 March 2007

Requiescat in pace

Contents

Kosciuszko is now spelled with a z, but for most of the period covered by this book it wasnt. Hence, while the modern form is adopted within the following pages, quoted material reflects earlier usage. As the Kosciusko Hotel burned down before the modern convention, its original spelling has been maintained.

Note that other modern usages also sometimes differ from quotations e.g. Monaro (Manaro) and Sakhalin (Saghalien).

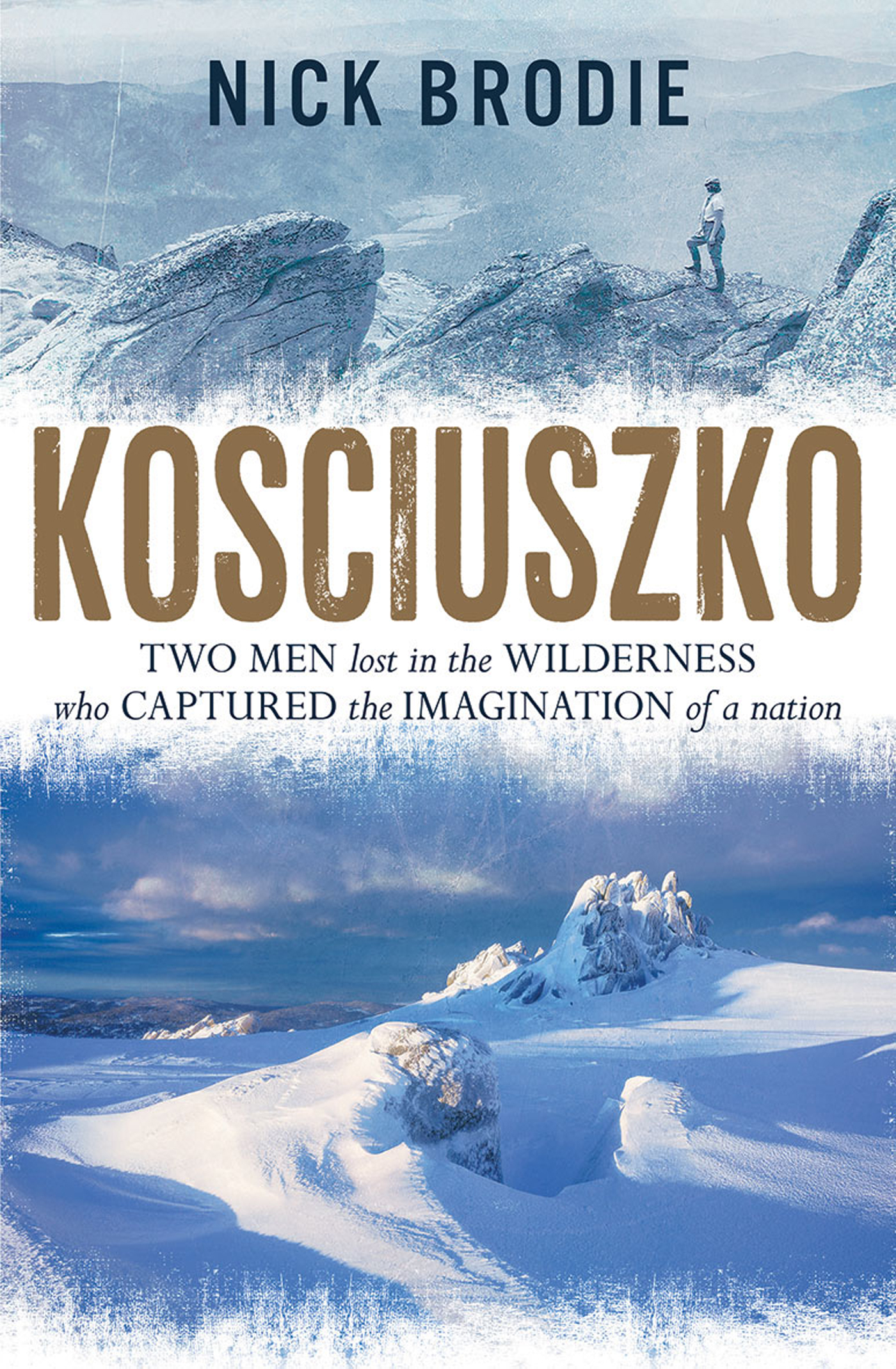

More than just our highest mountain, Kosciuszko reverberates in our national psyche in ways both perplexing and telling. Ours is an identity grounded in place and history wherein Kosciuszko has a special but easily overlooked part.

We seem to intuit that Kosciuszkos significance transcends height. It has an importance that is geographical and geological, but its effect upon us is also profoundly cultural. My ancestors lived up by Kosciuszkos side, and the mountain long called to me from that famous poem where a horseman rides out from Snowy River. I knew Kosciuszko before experiencing it, and I loved it without really knowing why. Kosciuszko was a part of me, and that was that.

But now Kosciuszko has called me back to address questions I had never thought to ask. Why does its very name ring in our souls? How has it shaped us?

Kosciuszko is at once inhospitable yet welcoming, untameable but familiar. It is a place of steadfastness amid the changing days and rolling storms of history, yet historys changes stand out especially clearly upon its sides and summit. We need such perspective in this age of division. By taking us higher, Kosciuszko helps us look further. On Kosciuszko, we see our story play out. From Kosciuszko, we see our story reach out.

Representing a tactile truth that transcends us all, Kosciuszko silently speaks of our deep past. For uncountable generations the alpine world in which Kosciuszko is situated provided rich summer food and witnessed the unifying effects of ceremony. Bogong, Bogong, one Aboriginal group told a perplexed colonial enquirer, rubbing their stomachs for emphasis. Following these people towards Kosciuszko he observed them gathering and consuming bogong moths, and caught a glimpse of Kosciuszkos ancient and unifying power. Drawing different peoples up into its heights, Kosciuszko brought many of Australias First Peoples together. Before the Commonwealth, before the First Fleet, before the Endeavour, Kosciuszko was a place where nations met and stories combined.

For untold centuries, from every compass point, they gathered each Kosciuszko season. They travelled from the coasts and the great river grasslands, up through the hilly forests, into valleys being carved by icy snowmelt, towards the rocky and treeless peaks that marked the nearest points to the heavens. And there in country traversed by the ancestors since the Pleistocene, that glacial age of great floods, they found companionship and nourishment. Kosciuszko was, and still is, a place of great communion.

The mountain once had many names. Associations of specific words with exact sites weakened under colonial times, when whole languages were driven into silence, but some words remain to remind us that this apparent wilderness is a living human landscape. Australias highest lake, nestled by the side of Mount Kosciuszko, is Lake Cootapatamba, a name bearing words both new and old. Other lost words may yet survive. One geologist in the 1850s was told by some Aboriginal people that Kosciuszko was called Piallow, a fact hiding in plain sight amid the newspapers of the past.

But Aboriginal names were not mere labels. They typically spoke beyond location and feature to ideas and emotions. One account had the term Gibbo used for these alpine regions, reportedly meaning snow mountains. The same term also referred to the initiation of young men with white ochre, hinting towards the spiritual significance for which Kosciuszko stands. Australias Snowy Mountains were never just a place, they were an allusion to holy ideas.

In this we are not alone. Like Ben Nevis, Fuji or Kilimanjaro the mere whisper of Kosciuszko conjures a sense of country. Like Sinai it encompasses the mysterious workings of history and eternity, becoming a place in and of lore. To be Australian is in essence to have lived beneath the peak of Kosciuszko.

Wherever in the world we go, that word Kosciuszko brings us home. Perhaps more than any other Australian place name, Kosciuszko captures our distinctive accent. We have modified the consonants and dropped at least one vowel from the original Polish pronunciation. For generations we misspoke the word into something new kozzy-osko taking it out of its precise historical context and reclaiming it in the process.

This history does similarly, taking Kosciuszko out of historical tradition and narrative convention. Like a mountain summit its focus is narrow, but its sweep is broad.

*

We learn and cherish Mount Kosciuszkos facts, but they quickly guide us to feelings. It stands 2228 metres above sea level. It is the highest portion of Australias Great Dividing Range, the stretch of mountains that effectively runs the length of Australias eastern coast. A continent with a bit of a reputation for being flat turns out to have one of the longest mountain ranges in the world, the result of an intercontinental collision some 300-odd million years ago. But while many of us will struggle to recall our lowest point, our easternmost, westernmost, northernmost and southernmost points, our longest and shortest rivers, most schoolchildren in Australia can answer in a flash that Kosciuszko is our tallest mountain. That swift recognition comes from something beyond geography. It speaks of a history that is like a collective memory, buried but not quite forgotten.

In part this reflects the way that our mythic history played out upon Kosciuszkos sides. This is the land of Banjo Patersons ballad The Man from Snowy River. The wiry little horseman who hailed from Kosciuszko steps from the shadows to ride brilliantly and vanish quickly. He stood in for an Australian everyman, a nameless icon of manly virtue and ephemeral humility. In his quiet confidence he challenged the bombast and hubris of our body politic, and remains a reminder that our greatest heroes are often nameless.

Yet while we feel its importance and our poetic heroes strut its sides, Kosciuszko gets left out of Australias history as it is often told. It is almost as if one of our most iconic landmarks does not quite belong in the national story. James Cook never climbed the mountain, Arthur Phillip never settled upon it, and its earth never soaked the blood of Gallipoli. Above the narratives, beyond the platitudes, this most Australian of places often stays out of our story and remains but part of the scenery.

Professor Ernest Scott, for instance, after whom the Australian Historical Associations most prestigious award is named, gave but three brief mentions to Kosciuszko in his A Short History of Australia. It first featured as a point of comparison for the height of the Blue Mountains, and last as a geographical landmark to help readers triangulate the situation of the new capital of Canberra.

That Strzelecki was safely guided into and through the mountains by Aboriginal men like Charlie Tarra went unmentioned in the great professors work. Yet without Tarra, the name Kosciuszko may well have stayed in the mountains. In that way, Kosciuszko speaks to the contradictions of our national story, and our failings of historical memory. It also shows that a small moment on the mountain, when read in clearer light, can reveal a greater historic vista and broader national truths.