Copyright Alan Leek

First published 2018

Copyright remains the property of Josh Langley and apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission.

All inquiries should be made to the publishers.

Big Sky Publishing Pty Ltd

PO Box 303, Newport, NSW 2106, Australia

Phone: 1300 364 611

Fax: (61 2) 9918 2396

Email:

Web: www.bigskypublishing.com.au

Cover design and typesetting: Think Productions Printed in China by Asia Pacific Offset Ltd

For Cataloguing-in-Publication entry see National Library of Australia.

Author: Alan Leek

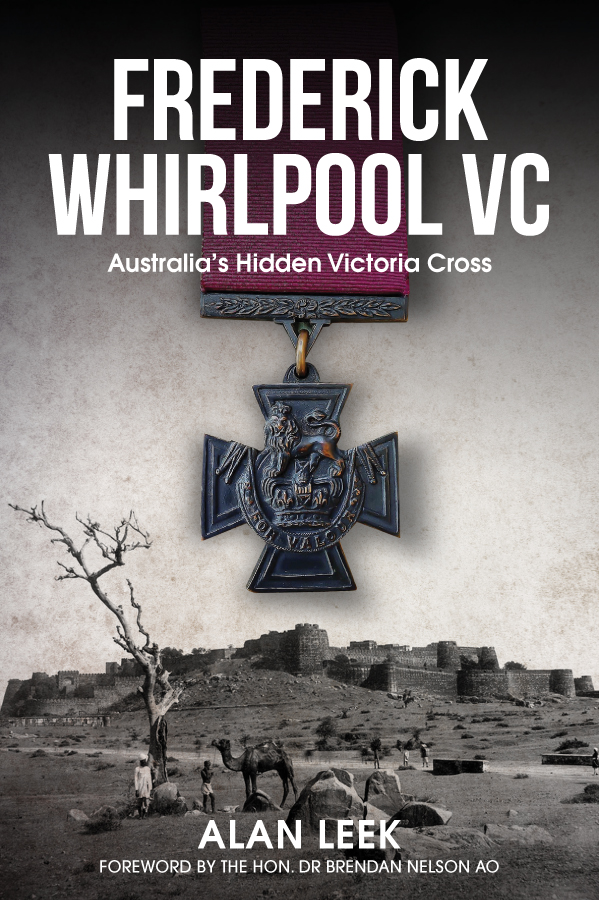

Title: Frederick Whirlpool VC. Australias Hidden Victoria Cross

ISBN: 978-1-925675-71-9

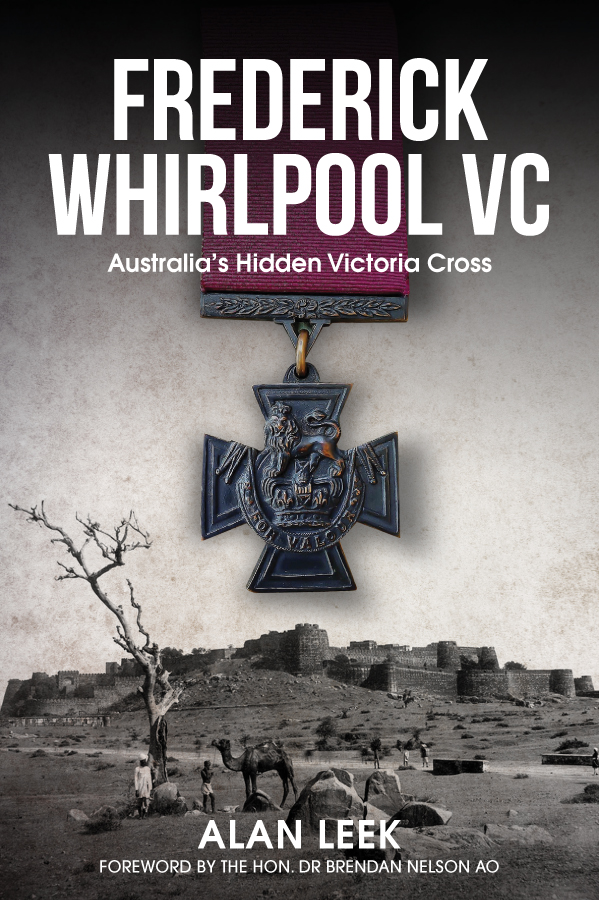

Cover images attributions:

Front - Walled city, palace and fort of Jhansi. Photograph attrib. Felice Beato c.1860.

Back - Blowing away from guns. Detail from painting by Vasili Vereshchagin 1842-1904.

Contents

For my grandchildren, Coen, Liam, April, Chloe, Rhys,

Millie and Evie. May they ever know peace.

Frederick Whirlpool, Australias hidden Victoria Cross is a detailed look at an intriguing man. Whirlpool has long been known as the first soldier in Australian uniform to be presented with the Victoria Cross. It was also known that he was fighting for the British East India Companys army when he earned the medal during the Indian Mutiny of 185758, and that Whirlpool was not his real name. Myth and error have surrounded almost all other aspects of his life.

In this book, Alan Leek attempts to set the record straight. He uses letters from the family, as well as official records and newspapers, to determine more about the mans early life under his original name of Humphrey James. As the author points out, the story has been difficult to put together, in large part because Whirlpool himself worked hard to obscure his origins and distance himself from his Victoria Cross. The medal was a burden to him, as were the lifelong injuries from the battle in which he earned it. The man behind that medal has remained in the shadowsuntil now.

Having migrated to Victoria in 1859 or 1860, Frederick Whirlpool joined the Hawthorn and Kew Volunteer Rifles. It was while wearing the uniform of this unit that he was invested with the Victoria Cross for his brave actions in India. Presented to him by

Lady Barkly, the Victorian governors wife, it was the first Victoria Cross presented publicly in Australia, and the first presented to a man in an Australian uniform.

To place the story of any individual soldier into the context of his time is a great challenge for military historians. This is even more true when researching the soldiers of the British Empire. Whirlpools world-spanning career was not unusualBritish soldiers were sent to all parts of the Empire. These soldiers left fragmented records in each place they visited, records that often pose as many questions as they answer. Leek, a former policeman, has brought his considerable detective skills to bear in writing this book.

Today, the Australian War Memorial is the custodian of Frederick Whirlpools Victoria Cross. It is displayed proudly in our Hall of Valour, beneath the Tomb of the Unknown Australian Soldier. There, the Memorial also commemorates the actions of the 100 Australian Victoria Cross recipients. Whirlpools story is distinct from those other recipients, and yet it too is a quintessentially Australian story. We witness in his story the same self-effacing bravery, the struggle to adapt to civilian life, and the burden of fame.

Frederick Whirlpool, Australias hidden Victoria Cross shows the strength of the connections between the nineteenth-century Australian colonies and the rest of the British Empire. It places Whirlpool into the broader context of his family, his service, and the world in which he lived. It is an admirable contribution to Australian military history.

The Honourable Dr Brendan Nelson AO

Director

Australian War Memorial

From the deep recesses of my earliest memories, two things are clear. First, the discomforting itch of clothing salvaged from surplus army uniforms; rough woollen cloth made to be durable in tough times, woven from the fleece of crossbred sheep, which at other times might have been used for carpets. In the immediate aftermath of the Second World War, nothing went to waste and my brothers and I were kitted like mini soldiers. Though I did not understand the reasoning behind the need to wear this discomforting rig, it seems that I always knew what khaki was and there was plenty of it to be had from burgeoning army surplus stores.

The second enduring memory is of visits to my paternal grandparents well ordered and modest home, and the splayed oak framed photograph of a young soldier, open faced and smiling slightly at the camera. The faux timber-grained mount, sepia toned and set against a gilt sleeve, lent gravitas to the image as it stared down from its prime position overlooking the dining table.

In front of the tiled hearth of the living room, I lay on the soft sheepskin rug and examined the dead mans penny, a British Commonwealth Memorial Plaque to the fallen, set in a honey coloured oak shield. I would later learn to read its inscription; Thomas Henry Markham, my grandmothers eldest brother. I dont recall my grandmother ever speaking of him, but he was always present. His memory had been charged to the women of the family and his mother had his photograph enlarged and framed, in a masculine manner, without mawkishness. She also had the penny mounted for timeless display, and sadly maintained his medals and the badges she wore, to show that she had sons serving at the front. Prominent among the campaign medals was the Military Medal for bravery, earned several months before he was blown to pieces at Ypres, in 1917, and passed out of the sight of men. Also safely lodged was the letter from his chaplain, advising of his death. These items were eventually passed to me, though I was never told of the actions that earned him his bravery award or those that led to his death. Nor did I understand the significance of the medals, apart from the Military Medal, which spoke for itself. Somehow I knew they were important, for these treasures instilled in me the need to ensure that his memory was maintained.

Growing up in the post Second World War period with crisp black and white films, some of them overt propaganda, cemented in a young mind some understanding of conflict, sacrifice and heroism. Overriding all of this was the understanding of and reverence for the Victoria Cross and its recipients. I grew up knowing the name of Frank Partridge VC and I mourned with the rest of Australia, his tragic death, almost twenty years after the end of hostilities. Albert Chowne VC, Edward Kenna VC and John Edmondson VC, were also household names. Who could not have known of Sir Arthur Roden Cutler VC, who would become Governor of New South Wales? It was also a time when Second World War servicemen were still reintegrating into their old lives, some with great difficulty, and even World War I veterans were plentiful. I wondered what might have been the story of my mathematics teacher, part of whose jaw had been shot away. He smelt strongly of liquor and cigarettes and had little patience with children, or perhaps, life. His challenges, already huge, must have been exacerbated by my inability at algebra and maths generally. We fought our own battles he winning by gruffly forcing my retreat into the corridor for each lesson, which in no way assisted my struggle. My early life was filled with the wonder and mystery of those who had served.

Next page