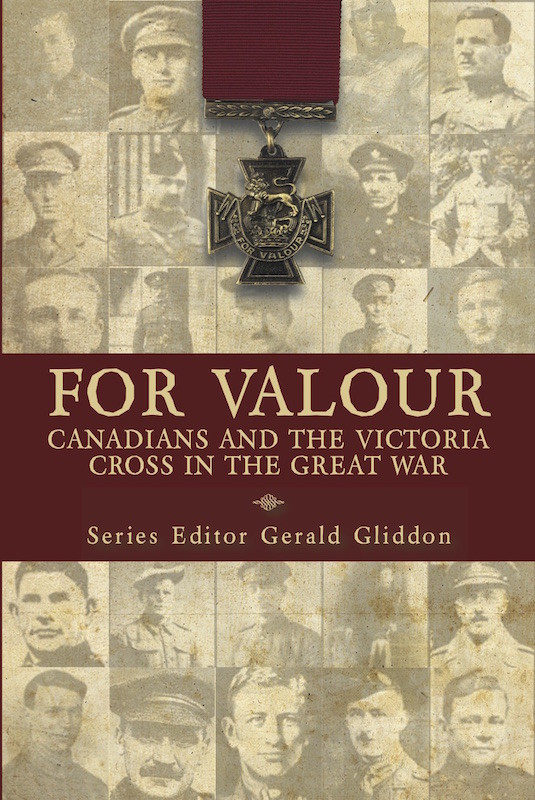

Cover

Table of Contents

- Abbreviations

- Foreword

- Introduction

- 19141915

- 1916

- 1917

- 1918

- Recipients with Canadian Connections

- Aftermath

- Appendix I

- Appendix II

- Sources

- Bibliography

The Victoria Cross was introduced by Queen Victoria on January 29, 1856, to honour acts of bravery during the Crimean War. The bronze cross bears the inscription For Valour, and is cast from the metal of captured Russian guns at Sevastopol during the Crimean campaign. It is based on the design of a Maltese Cross and has a one-and-a-half-inch crimson ribbon. The decoration also contains the holders name and date.

Queen Victoria made the first awards of the VC at a public investiture held in Hyde Park on June 26, 1856, and since then 1,356 have been awarded, the most recent being to Paratrooper Lance Corporal Joshua Leakey, in February 2015.

Abbreviations

ADS Advance Dressing Station

BEF British Expeditionary Force

Bn. Battalion

BVM British Victory Medal

BWM British War Medal

CAMC Canadian Army Medical Corps

CASC Canadian Army Service Corps

CEF Canadian Expeditionary Force

CFA Canadian Field Artillery

CIB Canadian Infantry Brigade

CO Commanding Officer

Col. Colonel

Cpl. Corporal

CSM Company Sergeant Major

CWGC Commonwealth Graves Commission

DCM Distinguished Conduct Medal

DFC Distinguished Flying Cross

DSO Distinguished Service Order

GC George Cross

IG Irish Guards

L/Cpl. Lance-Corporal

Lt. Lieutenant

Lt.-Col. Lieutenant-Colonel

Maj. Major

Maj.-Gen. Major-General

MC Military Cross

MG Machine-gun

MiD Mentioned in Despatches

MM Military Medal

MO Medical Officer

OTC Officer Training Corps

Pte. Private

RAMC Royal Army Medical Corps

Regt. Regiment

RE Royal Engineers

RNWMP Royal North-West Mounted Police

SAA Small Arms Ammunition

Sgt. Sergeant

Sgt.-Maj. Sergeant-Major

VC Victoria Cross

Foreword

The Victoria Cross, the highest gallantry medal for service to the British Commonwealth, was established by Queen Victoria in 1856, during the Crimean War. The Royal Warrant for the Victoria Cross stated that it may be awarded to persons who served the Crown in the presence of the enemy, and shall have then performed some signal act of valour or devotion to their country. Soldiers and sailors of all ranks were eligible, as were civilians acting under military command. According to the Royal Warrant no previous distinctions or qualifications, such as long service, wounds, or prior meritorious conduct, were to be taken into account when an application was made. The Victoria Cross is still awarded today for high gallantry in British or Commonwealth service.

The awarding of a Victoria Cross was and indeed remains an exceedingly rare distinction: less than 1/55th of 1 percent of the approximately 420,000 men and women who served with the Canadian overseas forces was decorated with the Victoria Cross during the First World War. Recommendations for a Victoria Cross required strong support from commanding officers and, usually, corroborating evidence from at least three eyewitnesses. General eligibility requirements for the decoration evolved during the war. For instance, by late 1916 authorities determined that it would not be awarded to soldiers who had rescued wounded comrades under fire, unless the potential recipient was a designated stretcher-bearer. During the latter part of the war Victoria Crosses typically went to men whose actions were courageous as well as bellicose. Soldiers who overran enemy strongpoints against steep odds, for example, were likely candidates. Lieutenant Samuel Honeys Victoria Cross, earned at Bourlon Wood in September 1918, is a case in point.

First World War British and Dominion soldiers undoubtedly took the award very seriously, although some felt that the medal was awarded inconsistently or perhaps too rarely. Since the eligibility requirements for the Victoria Cross were so rigorous, authorities introduced lesser awards, such as the Military Cross and the Military Medal, to recognize more equitably the innumerable acts of valour exhibited in battle.

The seventy-two recipients of the Victoria Cross whose stories are told in this book each clearly displayed incredible bravery on the battlefield. Interestingly, there is no obvious pattern of common traits in their backgrounds and few clues to suggest that any of them was destined for such a great honour. Captain Francis Scrimger was a thirty-four-year-old physician when he won the VC at the Second Battle of Ypres in April 1915. By contrast, Private Tommy Holmes, a frail, delicate youth with a contagious smile, was just nineteen years old when he won his VC at Passchendaele in October 1917. Captain Billy Bishop, surely Canadas best-known VC recipient, had failed his first-year exams at the Royal Military College of Canada. It is doubtful that any of Bishops instructors would have pegged him as a future war hero.

The variety of characters whom we find among Canadas First World War Victoria Cross recipients reminds us of the broad cross section of people who served in Canadian uniform during the war, or were otherwise associated with the Canadian overseas forces. While this book has been prepared to honour their courage in particular, it bears remembering that countless others performed unseen or unrecorded heroic acts that were never formally recognized with an award or honourable mention. Although the First World War is now a century past, and its veterans no longer walk among us, let this book serve as a reminder of the very great stores of courage that helped to bring the Allied forces to final victory.

Andrew Iarocci, PhD

Assistant Professor, Department of History

Western University, London, Ontario

Introduction

Canadas VCs of the First World War

The country of Canada was part of John Cabots discovery of North America in 1497, when the French and British laid claim to its lands and potential wealth. The French were the first to establish themselves, which they did on the northeast side of the country. The British established their colony on the Atlantic coast, and in the late eighteenth century moved northward from the United States into Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Lower Canada. Soon Britain occupied the majority of the lands to the east and west. In 1867 the two nations joined together in a confederacy, a Union of Upper British Canada and French Lower Canada, and the country became virtually self-governing. Even so, on paper the country was still subject to the rule of the English Imperial Parliament, which installed a Governor General.

The Boer War in South Africa broke out in October 1899. Three months later the Boers attacked Ladysmith. The war, in which the British Army had received a very bloody nose, ended on May 31, 1902. Canada had taken an active part in the campaign to restore law and order in South Africa, and in doing so had won five Victoria Crosses. The Boers, a skilful enemy, had adapted very well to the terrain and revealed a number of weaknesses in the structure and, more importantly, tactics of the British Army. Over the next twelve years a considerable amount of work was carried out in order to make an efficient, yet small, standing army that would be ready for any major European conflict.