VIKING

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

penguin.com

Copyright 2015 by Holly Bailey

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

by Sarah Schumacher

ISBN 978-0-698-17617-1

Version_1 C ONTENTS

For my mother

INTRODUCTION

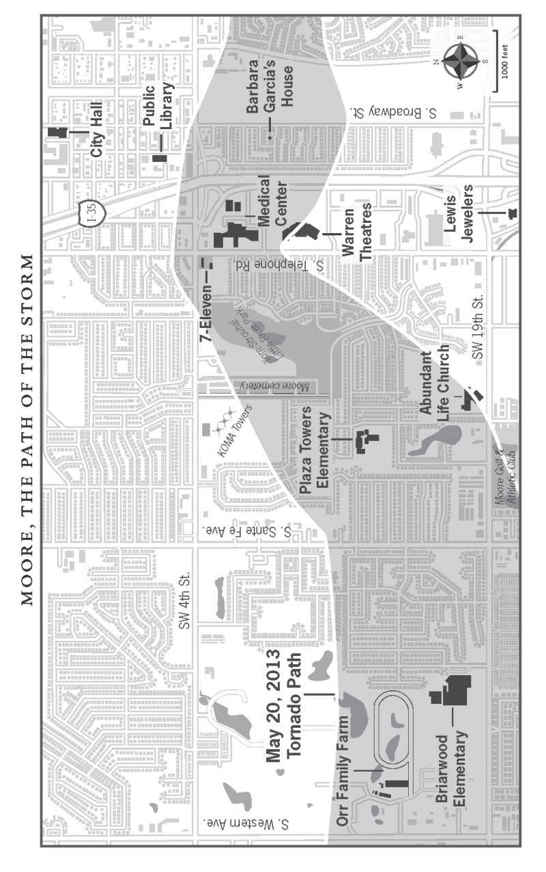

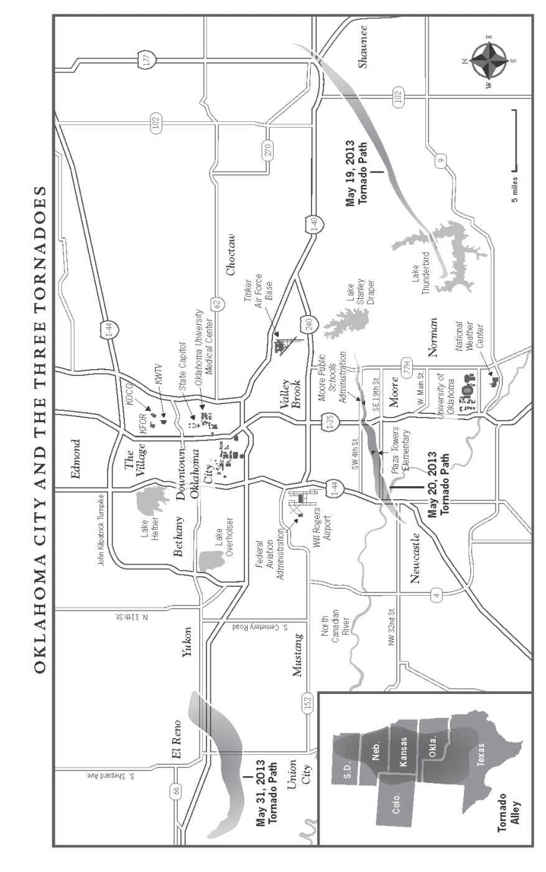

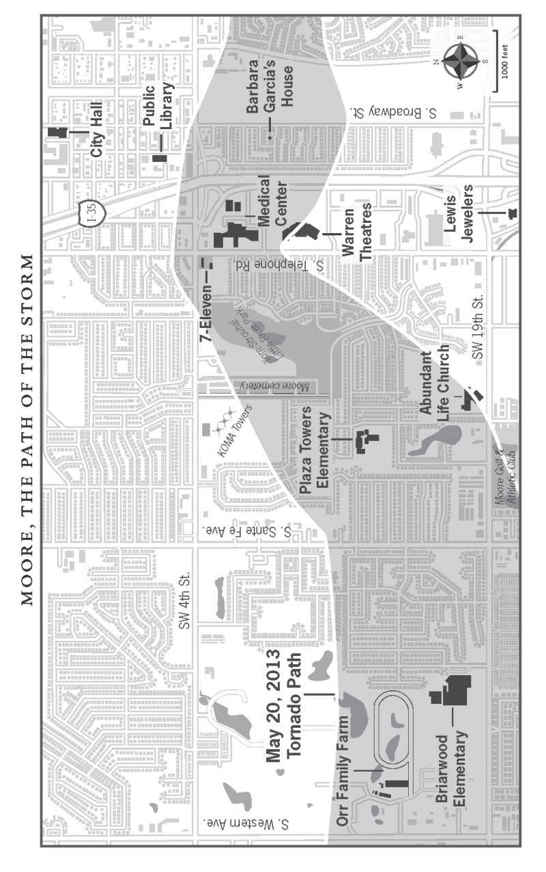

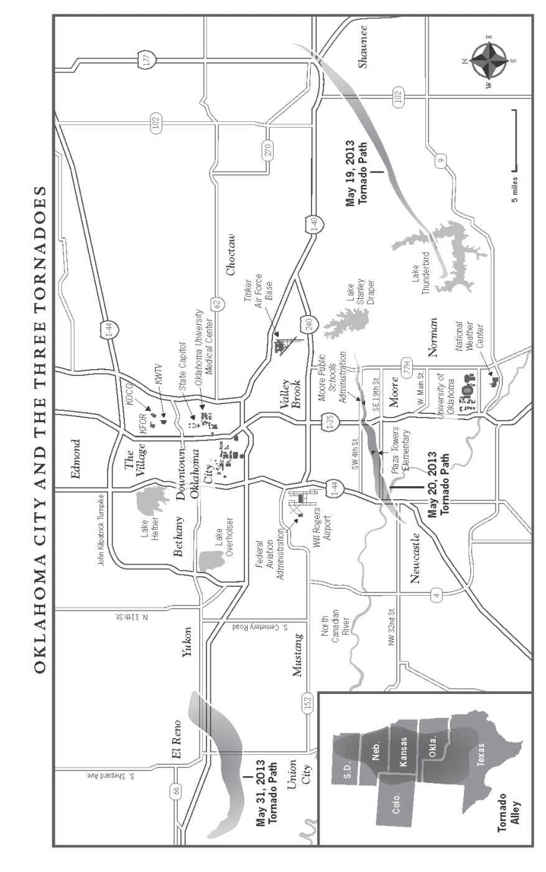

C entral Oklahoma has long been known as tornado alley, and anyone watching the news knows why. In May 2013 two of the strongest tornadoes on record hit the ground there in less than two weeks. On May 20 a milewide twister packing winds in excess of 200 miles per hour tore through the center of Moore, a quiet suburb south of Oklahoma City, killing twenty-five people and injuring several hundred. Among the dead were seven third graders at Plaza Towers Elementary, who died when their school building collapsed on top of them. It was the fifth tornado in fifteen years to sweep through Moore, a town that has been so unlucky with the weather that many locals refer to it as the tornado alley of tornado alley.

I spent most of my childhood in Moore. Though I lived a few miles away in south Oklahoma City, I went to school in Moore until I was fourteen, right on SW Fourth Street, a few blocks north of Plaza Towers. Many members of my family have called Moore their home over the years. Some still do, residing a mile north of where the May 20 tornado hit. Knowing their citys track record with the weather, they jumped in their car that Monday and fled the storm, looking in their rearview mirror and praying that they would have a home to come back to when dark clouds had passed. It wasnt the first time theyd had to run, and given Moores history, it probably wont be the last.

The May 20 storm bore eerie similarities to a tornado that had slammed into Moore almost exactly fourteen years earlier. That storm, which hit on May 3, 1999, was so devastating that many Oklahomans still refer to it by its date alonelike their own version of 9/11. The May 3 twister was another milewide monstrosity that killed thirty-six people as it cut a deadly diagonal from just south of Oklahoma City through Moore. More than five hundred people were injured, some so horrifically it was a miracle they survived. The storm caused more than $1 billion in damage. In Moore alone it wiped out several entire subdivisions on the west side of town, reducing them to ruins.

The May 3 storm remains the strongest tornado ever recorded in the nearly one hundred years since scientists have been trying to understand the mysterious phenomenon of the tornado. At one point its winds clocked in at 302 miles per hourthe highest wind speed ever measured near the surface of the earth. The storm may in fact have been stronger, but nobody could get close enough to measure it at the epicenter. Meteorologists studying tornadoes have been forced to keep a safe distance from their subjects. The 1999 storm was so destructive it prompted the National Weather Service to rethink how it measured tornadoes on the Fujita scale, which was launched in the 1970s to categorize storms by size and wind speed. In 2007 scientists adopted the Enhanced Fujita scale, which factors in the damage left in a tornados wake to more accurately gauge how strong it wasthough so much is still a guessing game.

In 2013 some neighborhoods that had been rebuilt after 1999 were hit againa destructive second act that has never happened to any other city. But just when it seemed it might be an exact replay of May 3, the May 20 tornado turned slightly to the east, taking aim at the heavily populated central part of Moore. At points it became wider and moved more slowly than the previous storm, becoming what is known as a grinder as it took its time chewing neighborhoods into tiny bits. The storm left behind more than $2 billion in damage, giving it the dubious distinction of being one of the most costly tornadoes in history. The May 3 tornado had been ranked as an F5the highest rating under the original Fujita scale. The tornado that hit fourteen years later was categorized as an EF5the highest possible rating on the updated scale. Moore was suddenly one of the only cities in the world to have been hit twice, in almost exactly the same spot, by two maximum-strength tornadoes.

Before Moore had a chance to fully digest its latest unlucky bout with the weather, the storm sirens sounded again. Just eleven days later, on May 31, an even larger storm developed to the west of the city. A tornado that was at least 2.6 miles widebigger than the width of Manhattantouched down in nearby El Reno, a few miles west of Oklahoma City, not long after Friday-evening rush hour. The El Reno storm, as it came to be called, is now the widest tornado on record. Fortunately, the tornado hit the ground in wide-open farm country, where houses were few and far between. Just as it began to aim east toward the more heavily populated city of Yukon, whose main road into town is named after its most famous son, the country singer Garth Brooks, and beyond that to Oklahoma City, it lifted, sparing Moore from another devastating hit. But it left behind irreparable damage. People still jittery over the May 20 tornado had jumped in their cars and tried to flee the storm at the last minute, clogging the roads as the twister approached. Four peopleincluding a mother and her infant son, born just seventeen days earlierdied when the storm sucked their vehicles off the roads on and near Interstate 40, where the tornados nearly 300-mile-per-hour winds picked up 18-wheelers and twisted them like tinfoil.

The twister had been moving straight east, but out of nowhere it quickly changed direction several times, erratically veering northeast, then heading due north as it grew into one of the most violent storms in history. It then literally made a loop over Interstate 40, turning around to hit land it had already hit. It swerved west, then southwest, then south, then southeast and east again, covering several miles in just minutes. Nobody had ever seen a storm like it, and as it unpredictably danced all over the landscape, the tornado was so gargantuan that no one on the ground realized it was changing direction. It was so massive it had multiple vortices swirling around inside itmonsters within the monsterthough you couldnt see them until you were right up on it, at which point you were too close to escape. With no warning, the massive twister turned on people who had been chasing the storm, including crews from the local television stations and The Weather Channel, who were sending live video feeds when the tornado began raining debris down on them. Some were picked up in their cars and hurled off the road. Many had spent their careers warning people to avoid the path of a dangerous tornado, and now they found themselves unexpectedly discovering the consequences firsthand.

Three veteran storm chasers died that night. Their white Chevy Cobalt was found half a mile from where it was lifted up by the storm, crushed like a crumpled-up soda can, and dropped in the middle of a canola field. Still buckled in the passenger seat was fifty-four-year-old Tim Samaras, one of the most respected tornado scientists in the world. But even Samaras, who was not a risk taker in his pursuit of the strange monsters he had devoted his life to studying, was caught off guard by the El Reno twister, a weather system so destructive that someone later said it seemed as if it had been designed specifically to kill storm chasers.

Next page