Introduction

I. The Anatomy of a Riot

When I set foot in Bhiwandi, I felt like I had seen this town somewhere before. Silence in every direction. The rare person on the rooftops, the empty streets, as if time had stopped. As soon as we entered town, we saw a few police outposts and the police sentries sitting outside them, in their uniforms. Some had taken off their uniform caps, some had unbuckled their belts, as if they were trying to rest after the riots. In places, we saw stray dogs. Silence in every directionand the people standing in their balconies and on their rooftops looked like statues. There was a kind of emptiness everywhere.

Bhisham Sahni, Todays Pasts

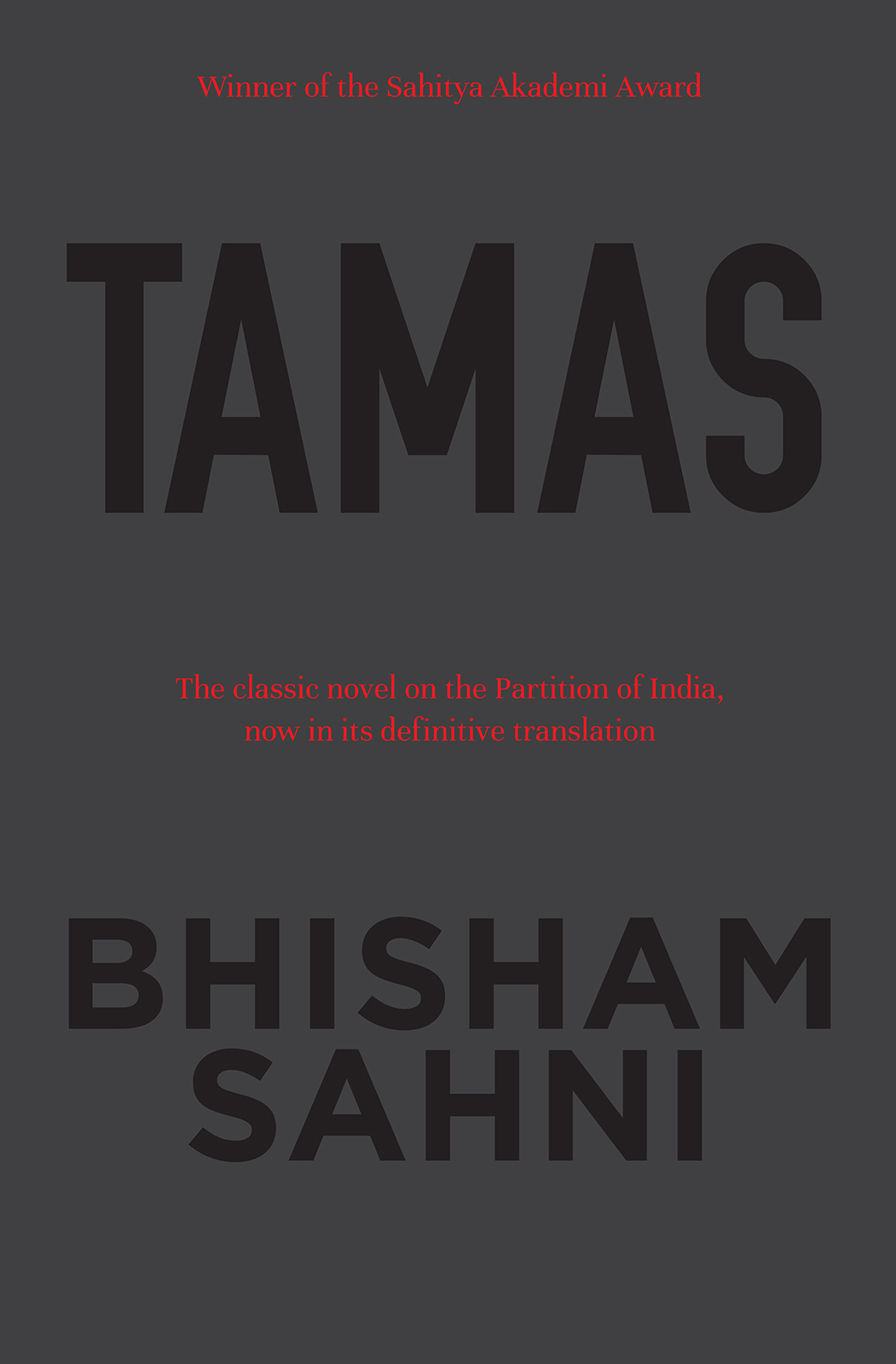

As a young Congress worker in Rawalpindi, Bhisham Sahni witnessed first-hand the rioting in March of 1947 that preceded the Partition; but it was not until he visited the town of Bhiwandi, outside of Mumbai, in the aftermath of the 1970 riots there, that he was inspired to write Tamas, or darkness. His intimacy with the politics of that historical moment, and with individual stories and motivations, gave him special insight that informed this, his best-known work. Thanks to Govind Nihalanis 1988 miniseries based on the novel, the work gained even greater popularity. After Premchands Godan, Tamas remains perhaps the best-known Hindi novel in English-reading India. And yet, Tamas is not the sort of novel youd expect to gain widespread popularity. Structurally, it is a highly unusual work, with no clear human protagonist. Readers who are not familiar with the novel will be confused as it slowly dawns on them that the real protagonist of Tamas is not a person at all, but the riot itself. Indeed, Tamas describes the anatomy of a riot, and it is the story of that riot that we follow through its nascent stages, as it gathers steam, then explodes in full force until it at last ebbs away, extinguished by the same hands that began it.

Sahnis meticulous, detailed chronicle gives the lie to the notion of Partition violence as a spontaneous burst of maniacal behaviour; of people losing control of themselves; of a madness that takes hold of the populace. This riot is the result of careful planning and politicking. Not only does Tamass darkness fall due to a concerted policy of Divide and Rule on the part of the British colonial administrators, but local politicians and religious leaders happily play their part in implementing the divisions and fomenting unrest. It is no surprise that Nihalani, despite his exacting recreation of the streets of pre-Partition Rawalpindi and an almost slavish devotion to portions of the original text, which are quoted verbatim in the film, decided that he needed to rewrite the story for the screenplay with a protagonist to follow throughout. In the novel, Nathu, the Chamar who slaughters the pig in the first scene, fades away in the second half of the book. At the very end, it is mentioned in passing that he is among those who have been killed in the violence. In the film, Nathu, played by Om Puri, makes it nearly to the end, and the final scene shows his pregnant wife giving birth in a refugee camp. The infants cries provide a coda for the violence that has produced two new nations.

Tamas the novel, however, offers us no such solace in neat endings, tidy narrative patterns, or relatable characters. Reading about the life of a riot is chilling and uncomfortable. As the violence subsides, and the leaders of all major political groups in the city board the peace bus, we are left with a sour taste in our mouths: The bus is being driven by the very man who commissioned the killing of the pig in the opening scene, and arranged for the carcass to be thrown in front of a mosque, thus inciting the riot in the first place. This man, Murad Ali, is a shadowy figure, a probable fixer for the urbane and soft-spoken British District Magistrate, Richard. Though no link is ever explicitly made between the two in the novel, one has the distinct impression that Murad Ali is the nefarious, unseen hand of the imperial administrator, acting at his behest to stir up unrest in such a way that all parties will sigh with relief when curfew is imposed and the army is stationed throughout the city. The mere appearance of a British pilot soaring low over the rooftops of the violence-ravaged villages is seen as a hand of God; all fighters drop their weapons and return to their daily lives the moment they see the plane and the friendly white pilot waving from the cockpit. Imperial order is restored, but the cycle is bound to repeat.

After all, Sahni wrote Tamas in the first place because he saw the cycle repeating in communal riots in independent India. The unseen hands may change, the locations may change, the match that lights the tinder may change, but the formula remains chillingly familiar. The notion of the communal riot, one that pits Hindu against Muslim or majority communities against Dalits, Sikhs, Christians, or Ahmadis may be very specifically South Asian, but Sahnis novel has much to teach the world about the fallacy of the notion that a riot is a spontaneous conflagration. Whether it is in Rawalpindi or Bhiwandi, whether in Ferguson, Missouri, or Baltimore, Maryland, a riot has deep roots and reflects decades of institutional violenceeverything from city planning, to municipal administrative policy, to policing techniques. Most importantly, as the character Dev Dutt, the local communist party leader, asserts, riots are the outcome of a concerted effort on the part of the rich and the privileged to distract the poor from common cause and pit communities against each other through racism, casteism and religious bigotry. A good riot is frankly useful to this cause because it serves to sharpen differences.

II. Multiple Translations

Tamas is one of those rare Hindi novels that has been translated not once, but twice. The first translation, by the indefatigable translator of Hindi and Urdu, Jai Ratan, was published in 1981. The second was undertaken by Sahni himself, who came to realize there were serious problems with the Ratan translation, and published in 2001. Ratans translation is marked by frequent omissions, inaccuracies and outright flights of fancy. Whilst Sahnis translation corrects these, he was unable to resist the impulse, common among authors translating their own writing, to edit and revise the original work. Consequently, changes appear mysteriously here and there when the inspiration hit him. Such rewrites or transcreations have an intrinsic value as literary works, especially for scholars hoping for more insight into the authors attitude about the text, but they do not convey the original text with fidelity.

It could also be argued that the miniseries Tamas was a third translation. As discussed above, Nihalani did make some major changes in the plot to create a more compelling screenplay, but very often he stuck doggedly to accuracy, and his recreations of street scenes and elaborate costuming were an amazing boon to this translator in helping to visualize articles of clothing and architectural features that are no longer in common use in South Asia. There was only one major change made by Nihalani that I found difficult to understand: In the novel, the District Magistrates wife, Liza, is a sloppy drunk. She may be driven to drink by her isolation and boredom, but shes frankly not the most sympathetic character. In the miniseries, by contrast, Lisa (her name has been slightly changed) is insightful and sympathetic. Though Richard tells her nothing, and she might drink one too many gin and tonics at cocktail time (in the novel, she is a beer drinker), she sees through his chilly disregard for humanity and worries about the plight of the people in the city. The end of the series shows her becoming a volunteer nurse at the refugee camp and calmly tending to the wounded. Perhaps Nihalani was uncomfortable with depicting the British characters as purely evil, though in the novel, Richard is portrayed as a complex character, one who pores over ancient Indian artefacts in his study and befriends Indian scholars.