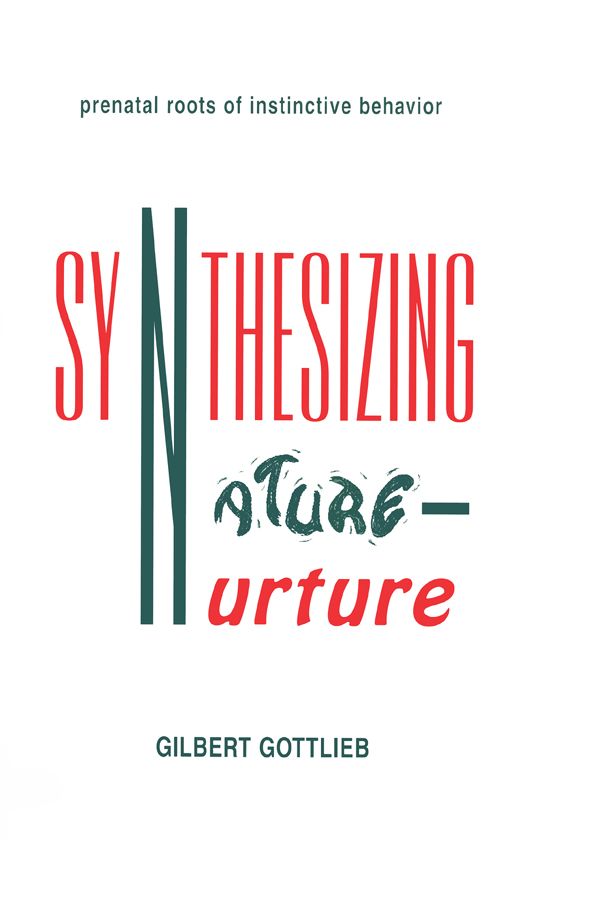

SYNTHESIZING NATURE-NURTURE

Prenatal Roots of Instinctive Behavior

Gilbert Gottlieb

University of North Carolina

at Chapel Hill

First Published 1997 by

Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc., Publishers

Published 2014 by Psychology Press

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

and by Psychology Press

27 Church Road, Hove, East Sussex, BN3 2FA

Psychology Press is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 1997 by Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Cover design by Nora W. Gottlieb

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Gottlieb, Gilbert, 1929

Synthesizing nature-nurture : prenatal roots of instinctive

behavior / Gilbert Gottlieb.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-805-82548-0(cloth) ISBN 978-0-805-82870-2(pbk.)

1. Mallard Behavior. 2. Epigenesis. 3. Nature and nurture.

4. Instinct. I. Title.

QL696.A52G67 1997

_____________________________________________

____________________________________________

Contents

_____________________________________________

____________________________________________

I was very fortunate early in my postgraduate career to have stumbled onto a research finding that kept me gainfully employed for 35 years. I recapture the high points of that intellectual adventure in the chapters to follow, but first I would like to describe the personal context out of which the research program actually developed.

Perhaps the reader should be forewarned that this monograph is not standard fare, because in each chapter I include relevant background considerations and autobiographical details that almost never get into journal articles or scientific monographs, but are nonetheless pertinent to an understanding of the intellectual path taken by the investigator and, thus, to an understanding of why the research program developed in the way that it did. Everyone knows that there is a significant personal side to science, but it is only rarely made public, largely because the tradition of scientific reporting discourages the recounting of personal considerations. Otherwise, this is the story of how the instinctive behavior of ducklings is created out of their experience in the egg.

GETTING STARTED: UNDERGRADUATE BEGINNINGS

I became a serious university student only after a 6-year hiatus in the real world between my sophomore and junior years. The most influential experience was service in the U. S. Occupation Forces in Europe after World War II. My job brought me into contact with displaced persons, and I was struck by the immense individual differences in coping under unusually stressful circumstances. I wanted very much to understand these individual differences and resolved to enter the field of psychology after my discharge. (It was, of course, naive to think that psychology could supply the answer, but it was an appropriate place to at least get oriented to the problem.)

After being discharged from the Army at the age of 24, I entered the University of Miami in my junior year in January of 1954. Although I was quite interested in the formal courses I took, I was thirsting for something beyond what I was being exposed to in the classroom, and suspected the professors were not telling all they knew. I spent a lot of time reading, not quite randomly, in the university library. I was drawn to books about evolution, books about embryology, late 19th and early 20th century theosophy, Freuds writings on psychoanalysis, and the Journal of Experimental Psychology. Although I was doing quite well in class, I understood little of what I encountered in my self-directed reading program and actively misunderstood what I encountered in the Journal of Experimental Psychology. My misunderstanding of the contents of JEP supported my ill-founded belief that the psychology professors were indeed holding back the choicest intellectual morsels in their classroom lectures. Why, in the pages of every issue of JEP, psychologists were reporting the outcomes of their experiments with the unconscious and conscious minds, not only of humans, but of rats! Fortunately, I kept these insights to myself, for such was my understanding that I thought the Pavlovian notations UCS (for unconditioned stimulus) and UCR (unconditioned response) were abbreviations for the unconscious and CS (conditioned stimulus) and CR (conditioned response) were abbreviations for the conscious. No wonder I did not understand anything I read in the JEP.

Along with my courses in psychology, I took many courses in philosophy as well as intellectual history (the history of ideas), because, while I was obviously quite intellectually naive, I did know the question I was interested in. I wanted to know the appropriate intellectual framework for coming to an understanding of events and things in the world. I dimly grasped that development (a persons history of experiences) was central to this understanding, so that is why I read Freud (on my own). Otherwise, my theoretical understanding was guided largely by an intuitive feeling of Tightness. Alfred North Whiteheads (1929) notion of the process character of reality seemed right to me as an undergraduate, as it still does today. Among other things, development signifies change.

In my senior year I had the good fortune, at the suggestion of an English professor, Richard Royce, to home in on three books that, at the time, completely satisfied my search for an appropriate metatheoretical framework for gathering valid insights into events and things in the world. My personal bibles were Dewey and Bentleys (1949) Knowing and the Known, Egon Brunswiks (1952) monograph on The Conceptual Framework of Psychology, and Harry Stack Sullivans (1953) The Interpersonal Theory of Psychiatry.

Dewey and Bentley described in a historical way how science has proceeded from self-actional explanatory frameworks (animism, self-acting souls or minds, instincts) to interactional frameworks (primarily Newtons mechanics), and, finally, to transactional frameworks (their term for seeing events and things in their full historical, cultural, evolutionary setting; a social and biological science derivative in harmony with field theory in physics). Whereas in the classical interactional explanatory framework the interacting bodies remain fundamentally unchanged (e.g., billiard balls only change their direction after they collide), in the transactional framework the components themselves become transformed (e.g., our present-day understanding of the consequences of infantcaretaker or peerpeer social encounters). At the University of Miami, I became such a vocal devotee of the transactional point of view that I raised these issues in and outside of class and was disappointed to find that, by and large, my psychology professors were ignorant of Dewey and Bentleys work, and, furthermore, at least one of them did not welcome this way of thinking about scientific explanation in psychology. I now recognize that I probably behaved as an arrogant nuisance in my eagerness to press my new-found knowledge on anyone within hearing distance.