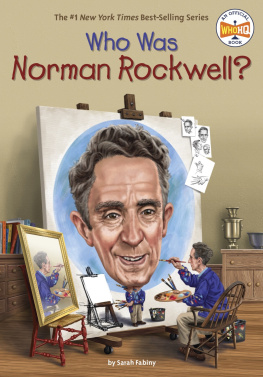

About Norman Rockwell: 332 Magazine Covers

Norman Rockwell (18941978) is not just Americas best-known magazine illustrator but one of its best-loved artists. Rockwell gave us a picture of small-town life that was familiar and at the same time unique: familiar because it was everyones dream of America, and unique because only he could portray it with such warmth and humor.

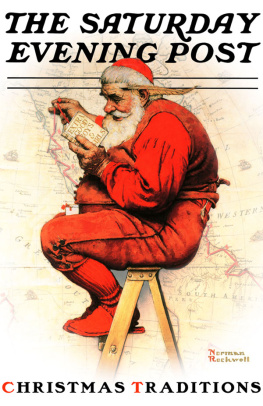

Rockwell did his finest work for the Saturday Evening Post, for which he painted more than three hundred covers between 1916 and 1963. Manylike Saying Grace, Breaking Home Ties, and The Marriage Licensehave achieved iconic status, and every one of them tells a story.

This book reproduces all of Rockwells Post covers, plus a selection of his early covers for other magazines, as crisp and vibrant color plates, with an introduction and commentaries by Christopher Finch, the noted writer on art and popular culture.

Norman Rockwell: 332 Magazine Covers is a longtime best seller in printed form. Now it is also the first e-book to present the timeless and heartfelt paintings of this American master.

Christopher Finch has written numerous books about popular culture, including Norman Rockwells America, The Art of Walt Disney, and Jim Henson: The Works.

Norman Rockwell: 332 Magazine Covers is also available as a clothbound hardcover and a Tiny Folio TM .

To view our complete selection of e-books, visit www.abbeville.com/digital.

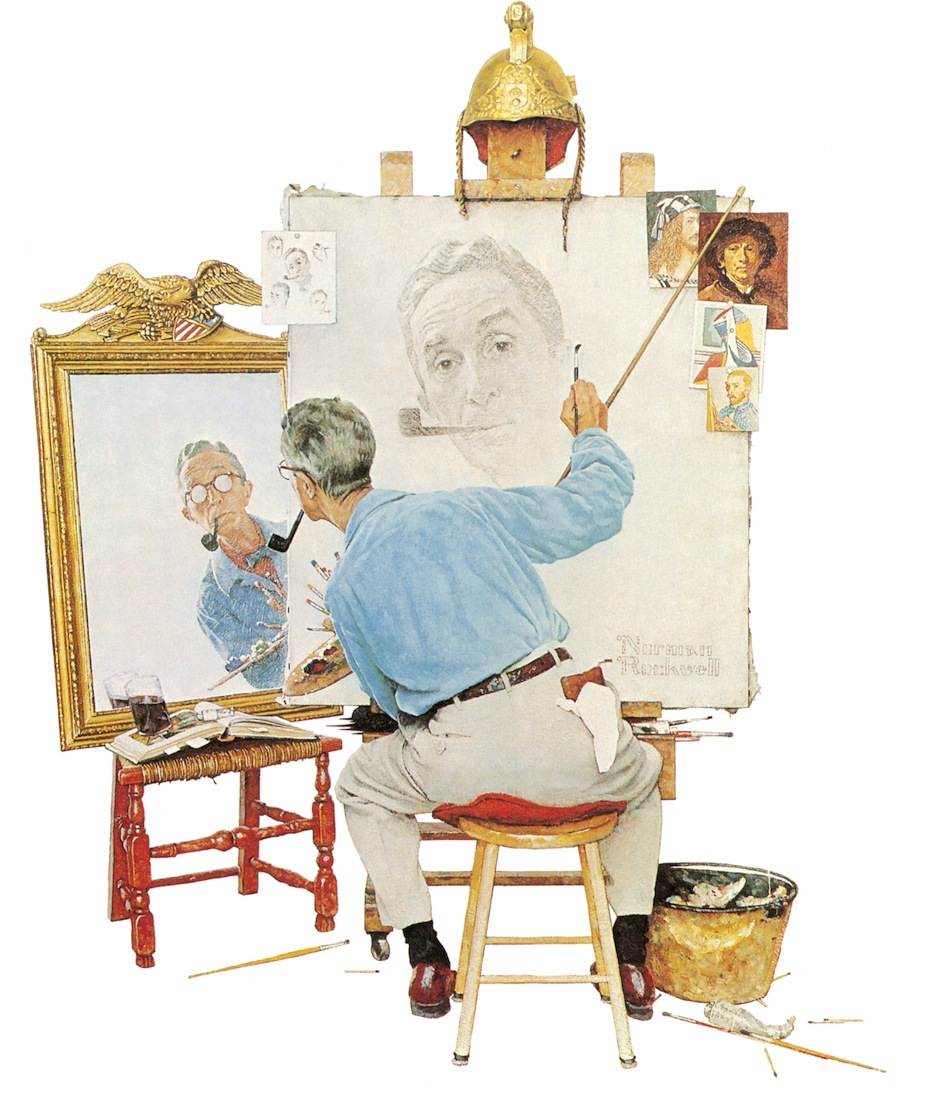

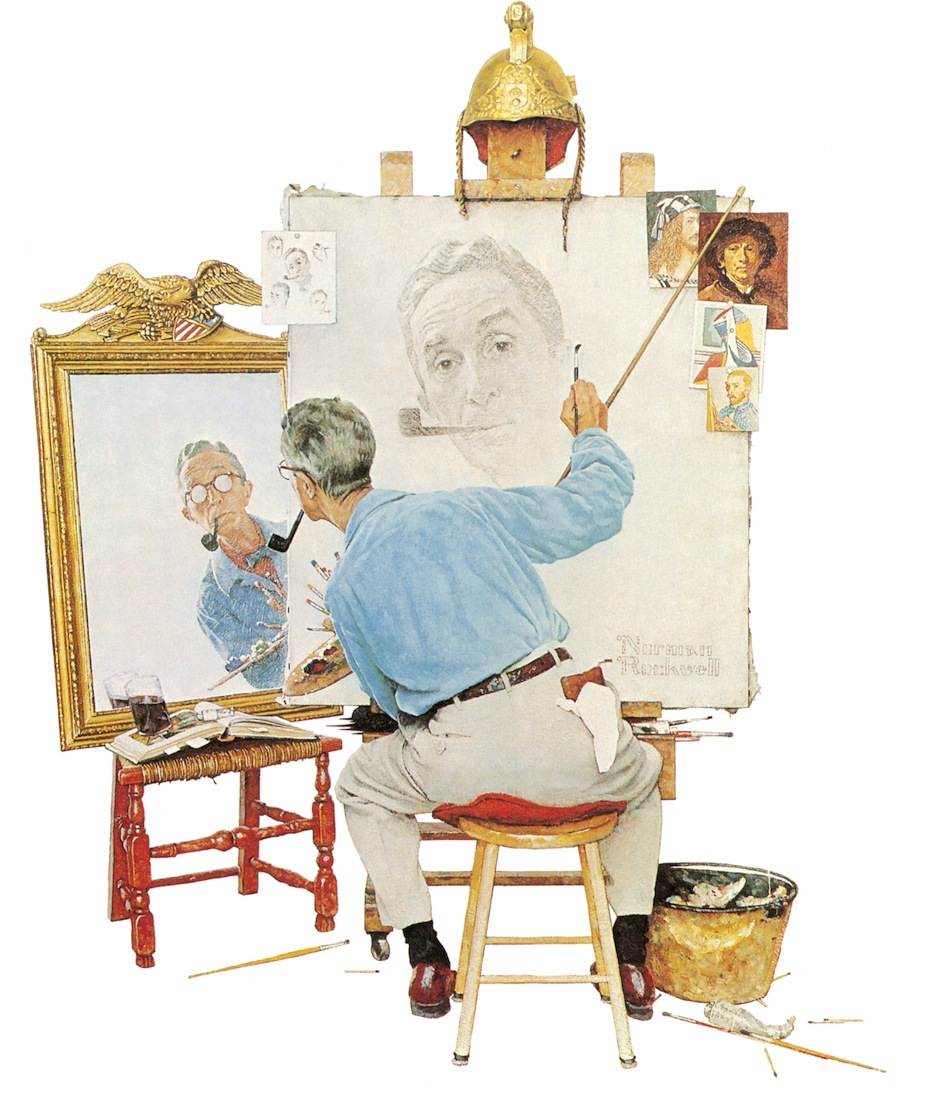

Triple Self-Portrait, 1960

(See .)

CONTENTS

Color Plates

The Saturday Evening Post:

How to Use This Book

Commentaries on the .

When viewing a plate, tap the image once to go to the corresponding commentary. Tap the image twice to see it in a full-screen, zoomable format.

When viewing a commentary, tap the thumbnail image or plate number once to go to the corresponding plate.

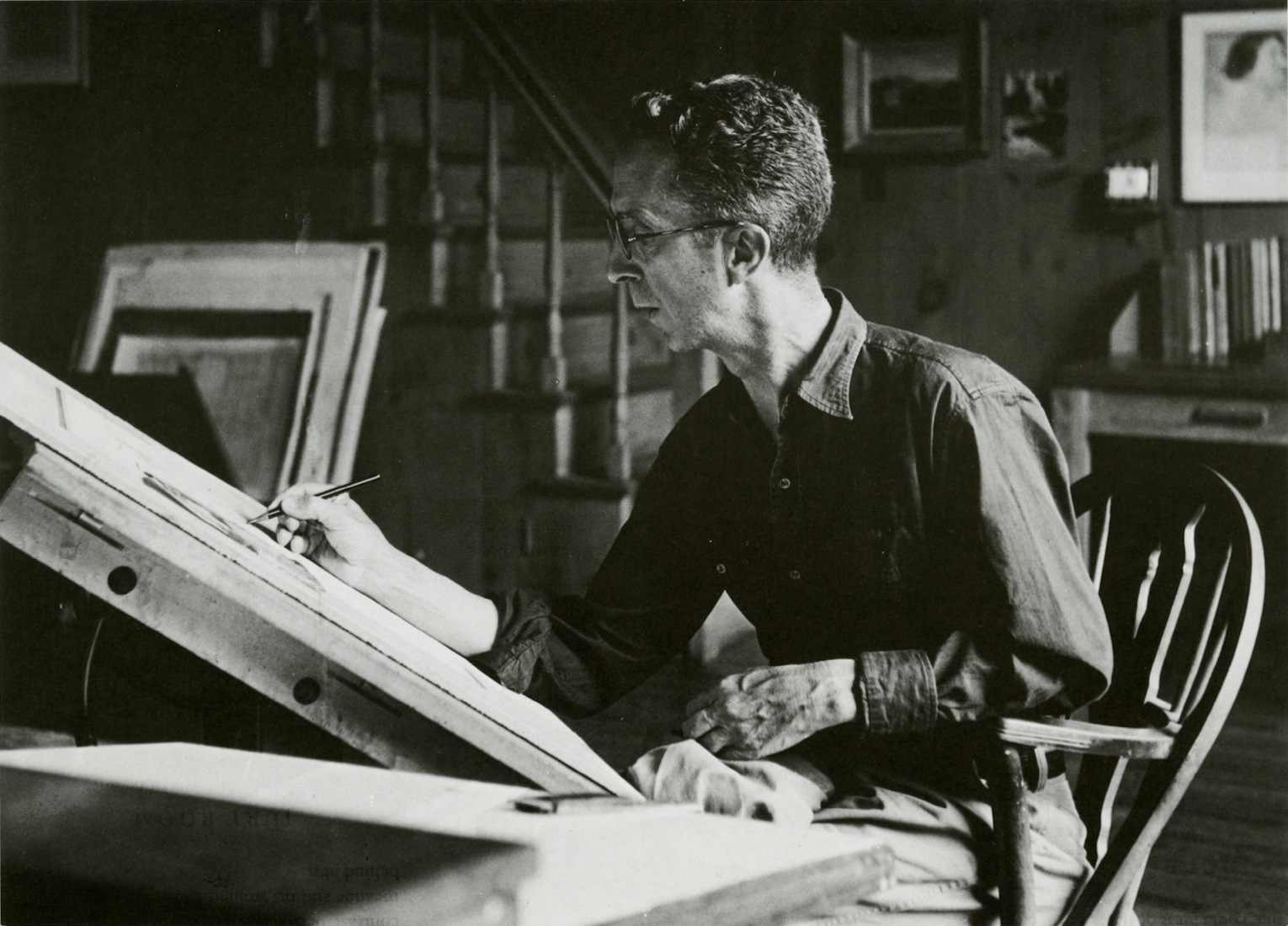

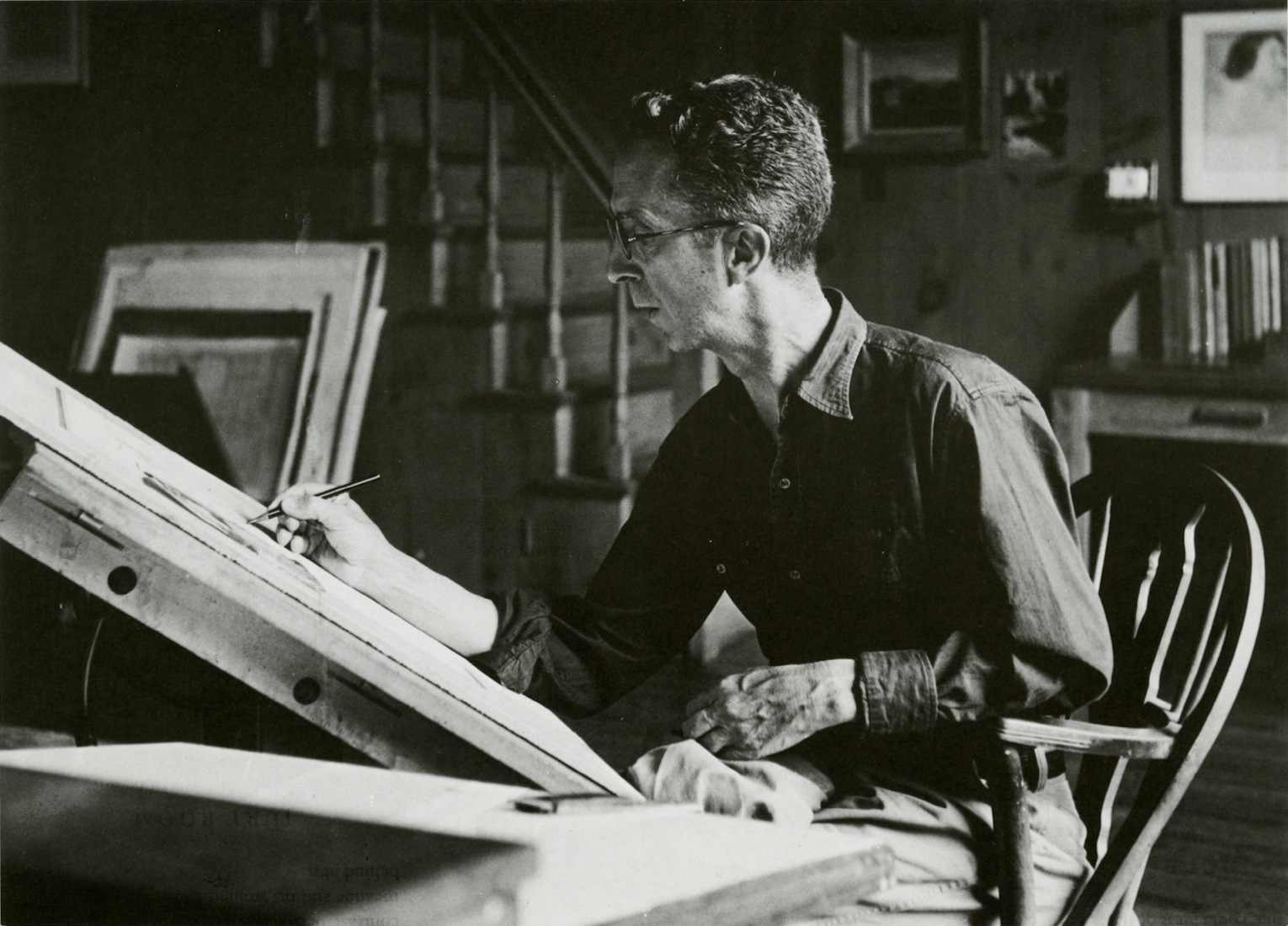

Norman Rockwell at work in his studio in Stockbridge, Massachusetts

Norman Rockwell Portrayed Americans as Americans Chose to See Themselves

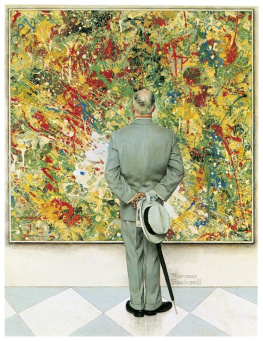

NORMAN ROCKWELL began his career as an illustrator in 1910, the year that Mark Twain died. He sold his first cover paintings when there were still horse-drawn cabs on the streets of many American cities, and he began his association with The Saturday Evening Post in 1916, the year in which Woodrow Wilson was elected to a second term in the White House and the year in which Chaplins movie The Floorwalker broke box-office records across the country. Young women were enjoying the comparative freedom of ankle-length skirts, and their beaux were serenading them with such immortal ditties as The Sunshine of Your Smile and Yackie Hacki Wicki Wackie Woo. In literature this was the age of Booth Tarkington, Edith Wharton, and O. Henry. Ernest Hemingway, still in his teens, was a cub reporter for the Kansas City Star, and F. Scott Fitzgeraldsoon to become a frequent contributor to the Post was still at Princeton. The New York Armory Show of 1913 had introduced the American public to recent trends in European painting, but traditional values still reigned supreme in the American art world. Only a handful of artists aspired to anything more novel than the mild postimpressionism of painters like John Sloan and Maurice Prendergast. The movies were becoming a potent force in popular entertainment, but few people took them seriously or thought they might one day take their place alongside established art forms.

It was a world in transition, but the transition had not yet accelerated to the giddy speed it would achieve in the twenties. People could be thrilled by the exploits of pioneer aviators without being conscious of the impact that flying machines would have on modern warfare. It was possible to enjoy the conveniences provided by such relatively new inventions as the telephone, the phonograph, the vacuum cleaner, and the automobile without being too troubled by the notion that technology might someday soon threaten the established order of things.

The illustrator and cover artist working in the mid-teens of the twentieth century was generally asked to embody established values. The latest model Hupmobile Runabout might well be the subject of a given picturean advertisement, perhapsbut the people who were shown admiring or driving in the newfangled vehicle were presumed to espouse the same values as their parents and their grandparents. The set of the jaw, the glint in the eye had not changed much since the middle of the nineteenth century. The women wore their hair a little differently, perhaps, and men were doing without beards, but these were superficial differences. The fact is that the minds of the people who edited and bought magazines like Colliers, Country Gentleman, Literary Digest, and The Saturday Evening Post had been formed, to a large extent, in the Victorian era.

Norman Rockwell himself, born on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, had a classic late Victorian upbringing. He spent his childhood in a solidly middle-class, God-fearing household in which it was the custom for his father to read the works of Dickens out loud to the entire family. Thus Rockwell had little difficulty in adapting to the conventions that were current in the field of magazine illustration at the outset of his career. Although a New Yorker, he was especially drawn to rural subject matter (he is on record as saying that he felt more at home in the country). This reinforced his affection for traditional idioms, since it focused his attention on the most conservative elements of the population, those who were least susceptible to change of any kind.

In short, Rockwell began his career right in the mainstream of the illustrators of his day, sharing the assumptions and concerns of his contemporaries and of the editors who employed him. His work is remarkable because he sustained through half a century the values that he espoused in those early days when the world was changing more drastically than anyone could have imagined possible. It would be easy enough, of course, to find fault with his refusal to break with those values, but that would be unjust. Rockwell simply continued to believe in what he had always believed in, and in his own way, he did, in fact, change and grow throughout his career. He learned how to embrace the modern age without abandoning his own principles. But he was also forced to modify and enrich his approach to the art of illustration in order to reconcile those principles to a world that was evolving so fast it seemed, at times, on the verge of flying apart.

His earliest paintings are conventional, almost to the point of banality, because the values they embody could be taken so much for granted. As he was forced to deal with a changing environment, however, he was obliged to become more inventive and original. A situation that could be presented in the simplest of terms in 1916, for example, might still be valid a quarter of a century later, but only if it were made more specific. Stereotypes had to be replaced by carefully individualized characters. More and more detail had to be introduced to make a situation more particular. As time passed, Rockwell was called upon to draw on all his resources as an illustrator in order to pull his audiencewhich was always changingalong with him. As circumstances became, theoretically at least, more hostile to his kind of traditional image-making, he rose to the challenge. His work became richer and more resonant, reaching a peak in the forties and fifties when most of the men who had been his rivals at the outset of his career were already long forgotten. His most remarkable quality was his ability to grow and adaptto remain flexiblewithout ever modifying the basic tenets of his art.

Next page