Deborah Solomon - American Mirror: The Life and Art of Norman Rockwell

Here you can read online Deborah Solomon - American Mirror: The Life and Art of Norman Rockwell full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2014, publisher: Picador, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

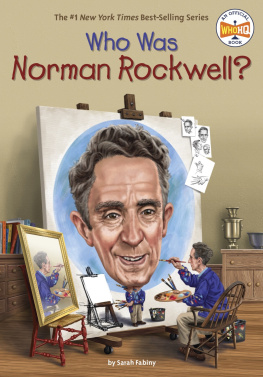

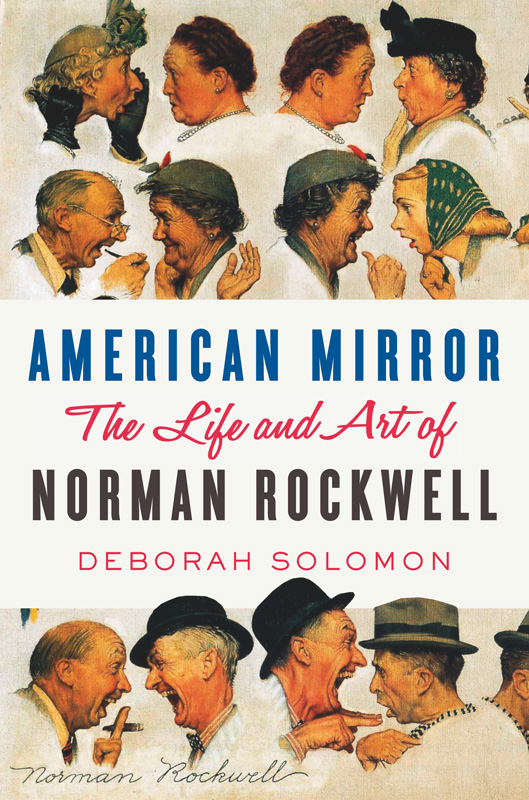

- Book:American Mirror: The Life and Art of Norman Rockwell

- Author:

- Publisher:Picador

- Genre:

- Year:2014

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

American Mirror: The Life and Art of Norman Rockwell: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "American Mirror: The Life and Art of Norman Rockwell" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

A NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW NOTABLE BOOK OF THE YEAR

A FINALIST FOR THE LOS ANGELES TIMES BOOK PRIZE IN BIOGRAPHY AND SHORTLISTED FOR THE PEN/JACQUELINE BOGRAD WELD AWARD FOR BIOGRAPHY

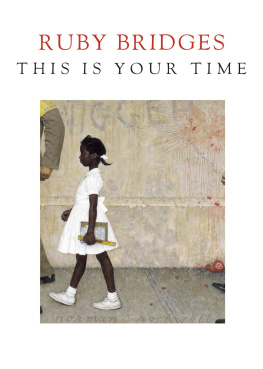

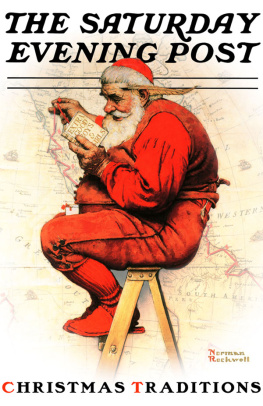

Welcome to Rockwell Land, writes Deborah Solomon in the introduction to this spirited and authoritative biography of the painter who provided twentieth-century America with a defining image of itself. As the star illustrator of The Saturday Evening Post for nearly half a century, Norman Rockwell mingled fact and fiction in paintings that reflected the we-the-people, communitarian ideals of American democracy. Freckled Boy Scouts and their mutts, sprightly grandmothers, a young man standing up to speak at a town hall meeting, a little black girl named Ruby Bridges walking into an all-white schoolhere was an America whose citizens seemed to believe in equality and gladness for all.

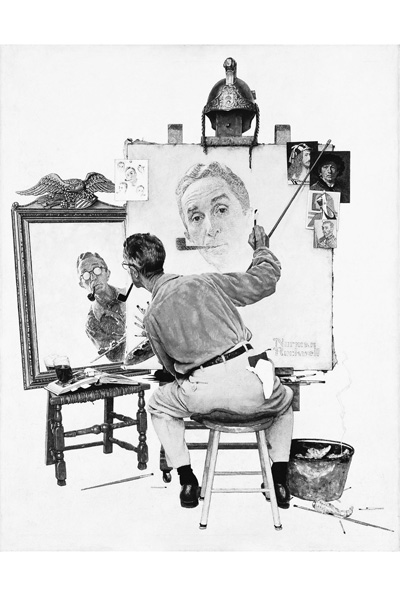

Who was this man who served as our unofficial artist in chief and bolstered our countrys national identity? Behind the folksy, pipe-smoking faade lay a surprisingly complex figurea lonely painter who suffered from depression and was consumed by a sense of inadequacy. He wound up in treatment with the celebrated psychoanalyst Erik Erikson. In fact, Rockwell moved to Stockbridge, Massachusetts so that he and his wife could be near Austen Riggs, a leading psychiatric hospital. Whats interesting is how Rockwells personal desire for inclusion and normalcy spoke to the national desire for inclusion and normalcy, writes Solomon. His work mirrors his own temperamenthis sense of humor, his fear of depthsand struck Americans as a truer version of themselves than the sallow, solemn, hard-bitten Puritans they knew from eighteenth-century portraits.

Deborah Solomon, a biographer and art critic, draws on a wealth of unpublished letters and documents to explore the relationship between Rockwells despairing personality and his genius for reflecting Americas brightest hopes. The thrill of his work, she writes, is that he was able to use a commercial form [that of magazine illustration] to thrash out his private obsessions. In American Mirror, Solomon trains her perceptive eye not only on Rockwell and his art but on the development of visual journalism as it evolved from illustration in the 1920s to photography in the 1930s to television in the 1950s. She offers vivid cameos of the many famous Americans whom Rockwell counted as friends, including President Dwight Eisenhower, the folk artist Grandma Moses, the rock musician Al Kooper, and the generation of now-forgotten painters who ushered in the Golden Age of illustration, especially J. C. Leyendecker, the reclusive legend who created the Arrow Collar Man.

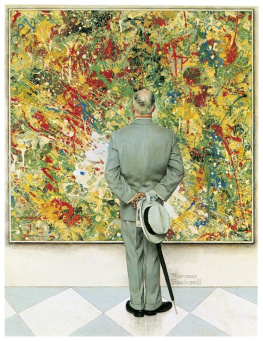

Although derided by critics in his lifetime as a mere illustrator whose work could not compete with that of the Abstract Expressionists and other modern art movements, Rockwell has since attracted a passionate following in the art world. His faith in the power of storytelling puts his work in sync with the current art scene. American Mirror brilliantly explains why he deserves to be remembered as an American master of the first rank.

Deborah Solomon: author's other books

Who wrote American Mirror: The Life and Art of Norman Rockwell? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.