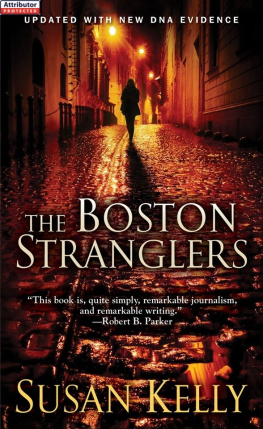

The Boston Strangler

Gerold Frank

A Note to the Reader

This book, which has taken on a shape and a direction I could not anticipate when I began, has been an extraordinary experience for me. I have lived it as well as written it.

I first became interested in what was taking place in Boston in the late summer of 1963. At that time there had been a series of murders of single women, most of whom were middle-aged, under circumstances as baffling as any in fiction. Each woman had been strangled in her apartment. There were no signs of forcible entry. Around the necks of the victims were knotted nylon stockings or other articles of their apparel. Each woman had been sexually molested or assaulted. No clues were found; nothing had been stolen; there was no discernible motive. The victims were, so far as could be determined, modest, inconspicuous, almost anonymous women, leading blameless lives. Beyond the mystery of their deaths, there was something terribly sad and pathetic about these victims who apparently either knew or were unafraid of their murderer, and let him into their apartments and did not even put up a struggle before they were finished off. It was obvious that the murdereror murdererswas insane. As a result, Boston was a city near panic.

As a young reporter I had had my fill of crime. I had covered electrocutions in Sing Sing prison, and had never gotten over the sight of murderers in the electric chair, nor the sense that we, the spectators, were outraging decency by witnessing the last private moments of these men. Later, as a foreign correspondent, I had reported riots, revolutions, and political assassinations. Sudden death was not unknown to me and I was not particularly eager to explore the subject again. My interest, therefore, was not so much in writing a book about the Boston stranglings as it was to write about what happens to a great city when it is besieged by terrorterror stemming from a horrifying explosion of the violence that seems more and more a part of contemporary life. How do people behave in a climate of fear? What defenses do they put up? To what extremes are they driven? How does rationality cope with irrationality, common sense with hysteria?

The city, then, was to be my subjectand the victims. For if these murders were, as it appeared, utterly senseless, why should these women have been chosen to die? What brought them to this place, at this moment in time, so that their lives met that of their assailant, moving about the city tortured by some private anguish of his ownDeath incarnate?

But it turned out that this was only the prologue. I could not know then that for the next three years I would be possessedand obsessedby this story as it grew and unfolded under my hand, as murder succeeded murder and new victims were strangled even while I was on the scene. I found myself, without having planned it, becoming the historian of a singular chapter in American social history: one of the worlds greatest multiple murders, one of the most exhaustive manhunts of modern times, and finally, what is surely the most extraordinary and sustained self-revelation yet made by a criminal.

As the only writer completely involved with the case, I was given the fullest cooperationnot only in Boston but in the neighboring towns where the stranglings and other crimes also occurred. The result is that everything that is in this book is based on fact. In some instances the identities of certain persons have been disguised but these persons were and are real. What appears in the following pages comes not only from my research and from hundreds of hours of personal interviews with the principal actors in the drama, and with scores of other participants, but also from the actual documentationthe police and court records, the medical and psychiatric reports, the transcripts of interrogations (some under hypnosis and hypnotic drugs), and the letters, diaries, and other source papers.

In short, the words and thoughts of the hunters and the hunted are not my invention but are, within the limits of human error, true. Unavoidably, errors will have crept in; mistakes in emphasis and interpretation will have been made; but in all instances I have done my best to mirror faithfully what went on in Boston in the time of the Boston Strangler.

GEROLD FRANK

New York, August, 1966

Part One

Part Two

Part Three

Part Four

The Dead

JUNE 14, 1962 | Anna Slesers, fifty-Five 77 Gainsborough Street, Boston |

JUNE 30, 1962 | Nina Nichols, sixty-eight 1940 Commonwealth Avenue, Boston |

JUNE 30, 1962 | Helen Blake, sixty-five 73 Newhall Street, Lynn |

AUGUST 19, 1962 | Ida Irga, seventy-five 7 Grove Street, Boston |

AUGUST 20, 1962 | Jane Sullivan, sixty-seven 435 Columbia Road, Boston |

DECEMBER 5, 1962 | Sophie Clark, twenty 315 Huntington Avenue, Boston |

DECEMBER 3 1, 1962 | Patricia Bissette, twenty-three 515 Park Drive, Boston |

MAY 6, 1963 | Beverly Samans, twenty-three 4 University Road, Cambridge |

SEPTEMBER 8, 1963 | Evelyn Gorbin, fifty-eight 224 Lafayette Street, Salem |

NOVEMBER 23, 1963 | Joann Graff, twenty-three 54 Essex Street, Lawrence |

JANUARY 4, 1964 | Mary Sullivan, nineteen 44A Charles Street, Boston |

AND |

JUNE 28, 1962 | Mary Mullen, eighty-five 1435 Commonwealth Avenue, Boston |

MARCH 9, 1963 | Mary Brown, sixty-nine 319 Park Avenue, Lawrence |

Dates are the original police estimates.

This is a story about Boston. It is a true story, about the people in it, what happened to them, and the strange and implausible events that took place there in a time which is today andman being the creature he ismay again be tomorrow.

It begins on Thursday, June 14, 1962.

That day, under a sky that threatened rain but never carried out its threat, Bostonians went about their businessconcerned with their private or public affairs, legal or illicit, generous or self-serving, history-making or utterly unimportant. Yet if we hold a microscope to it it becomes something of a special day.

In Cambridge, across the Charles River, Harvard University was holding its 311th Commencement, and in the Yard thousands of students, alumni, and guests were gathering about the buffet tables set up under canvas, heavy with the traditional chicken salad and beer. At 4:15 P.M. , the sun came out from behind the clouds: since Boston had known only rain these last few daysit had forced cancellation of the Harvard-Yale baseball game the day beforethat was a signal for everyone to break out in a mighty song, Fair Harvard. The ancient bells of Memorial Church chimed in, echoing across the campus.

At that time, through the Back Bay and downtown districts of the city itself, some 100,000 Bostonians lined the streets cheering Commander Alan B. Shepard, Jr., the nations first astronaut. The man who had ridden the nose of a rocket more than a hundred miles above the earth a year before had come to his hometown, nearby Derry, New Hampshire, to receive a New England Aero Club award and be guest of honor on that dayFlag Dayat ceremonies on Boston Common. He stood in the back of a convertible, a shining, handsome man, and as he rode by the applause rippled up the street.