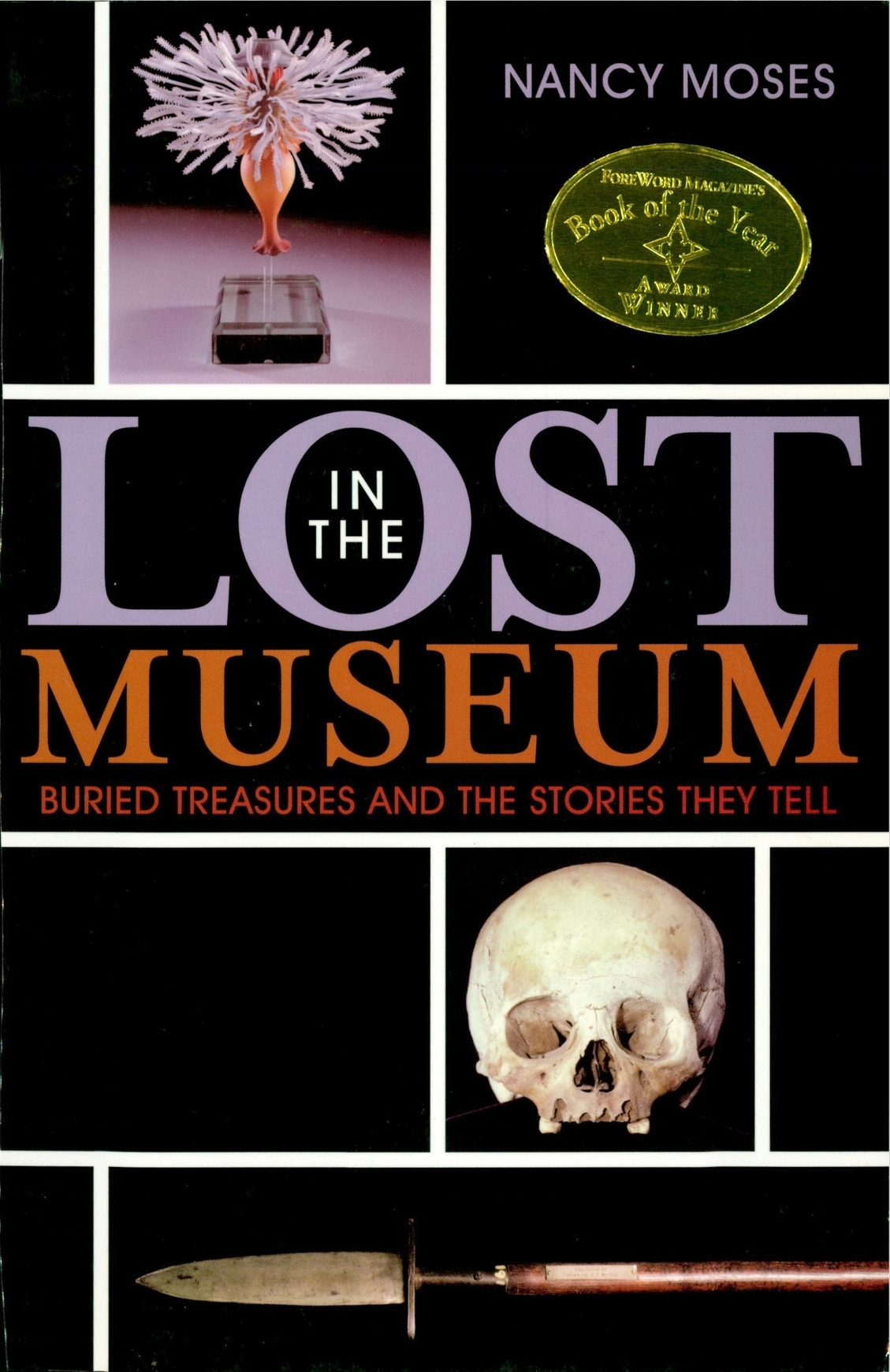

A former museum director, Nancy Moses has spent much of her career bringing history to lightand to life. Her articles and opinion pieces on civic heritage have appeared in the Wall Street Journal, Philadelphia Inquirer, Boston Globe, and other publications.

Nancy served as a delegate to the White House Conference on Travel and Tourism and to President Clintons Summit on Volunteerism. She holds a masters degree in American civilization from The George Washington University and lives in Philadelphias historic Society Hill along with her husband, Myron, and poodle, Frederick.

EPILOGUE

I began this journey through a selection of collecting institutions to search for the behind-the-scenes lessons that all of them hold. I uncovered four of them.

The first lesson is that every collecting institution is itself an artifact with a singular story to tell. Each museum, special collections library, historical society, and archive is born at a specific moment in time, reacts to specific challenges and opportunities, deals with its collections, and connects with its communities in different, often idiosyncratic ways. All follow an evolutionary path that mirrors the path of society. Earnest amateurs founded most museums. Over time, in response to societys evolving needs and values, these institutions morphed into an international mega-cultural industry where public entertainment is almost as important as public education, and where armies of professionals now stand in the places where a few amateurs once stood.

How collecting institutions respond to the ever changing American landscape leads to the second lesson, which confirmed my own experience as director of the Atwater Kent. These places are very tough to manage and even tougher to change. They move at a pace that appears glacial to those in the private sector, but for good reason. Its very tricky to balance competing missions, and trickier still to start something new when there are so few dollars and thus so little room for error. Every day in a museum directors life brings another wrenching choice, for theres never enough money to simultaneously satisfy every priority, to do everything right.

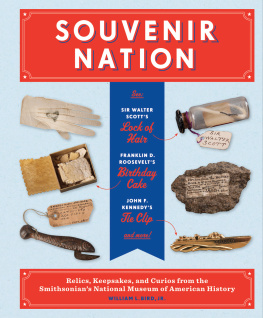

The third lesson gets to these priorities. Whats most important: exhibits or collections? When I directed the Atwater Kent Museum, the answer seemed obvious: public exhibits had to come first, since unless the public came, the mayor of Philadelphia would close our doors. What I later realized, quite to my surprise, was something different. If you believe in the intrinsic, civic value of collecting institutions, theres really no choice. Collections must come firstthe bones and birds, diaries and documents, creations of master and minor artists, relics, charms, talismans, souvenirs, specimens, and heirlooms. This stuff is the stuff of the scholarship, science, and exhibitions of the future. Preserving it for posterity is the most important thing collecting institutions do.

Whether its the family portrait hanging in your parlor or the extinct species lying in a drawer in a museums storage cabinet, the objects we save are touchstones; they tell us who we are. Objects bring forward our personal memories and bind them to the larger story of society. By saving the stuff lost in the museum, we allow future scholars, curators, and visitors to explore themselves in relation to their material heritage. Each succeeding generation brings its own questions and fresh perspectives. Marginal artists are rediscovered and celebrated; specimens are reexamined and new species emerge; segments of society once hidden from view are revealed and celebrated. Years ago, no one would have imagined that todays historians would search archives for clues to the roles that gays and lesbians played in society. But they do. And they couldnt unless past archivists saved the documents.

There are way too many treasures buried in the crypts, but they do not have to remain hidden. Many institutions are finding imaginative ways to bring more of their stuff to public view. The most exciting one is the Internet. Places like the Athenaeum of Philadelphia and the Mtter Museum of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia are digitally documenting their holdings and making them accessible to all via their websites, as will the Barnes Foundation soon. The Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh and many others are staging temporary exhibitions that bring fresh interpretation to long-lost treasures. Some are offering behind-the-scenes tours. Others are building open storage areas, shelves lined with objects behind walls of glass, so visitors can walk by and view them in situ.

These efforts are critically important. Theres no other way to convince the public to invest in preservation of the 630 million items that Heritage Preservation and the Institute of Museum and Library Services found in need of immediate care. Studies like these help collecting institutions reveal their massive hidden holdings and justify the costs of preserving them. People dont give to causes they cant see.

Which brings me to the final lesson I learned, and it was the most surprising. Every collecting institution, regardless of size, type, age, or collecting practice, is a storehouse of stories just waiting to be told. And while museum professionals are delighted to show off their favorite treasures, they can lose perspective on what the public would most enjoy. Thats where museum visitors can help by sharing their preferences, interests, and perspectives on the stories that resonate most. The Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture is a stunning example of the exhilaration that emerges when the very process of museum making is a collaboration between professionals and community members. Unlock the doors and share the stuff.

My journey of discovery began at the Atwater Kent Museum, so its fitting that it ends there too. The metal toy train that curator Jeffrey Ray showed me during my first week on the job is still there, along with the 80,000 other objects. In fact, there are more, because the collection now includes the art and artifacts of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. Under the management of a thoughtful and seasoned executive director, all are now safe, secure, and preserved for our children and our childrens children.