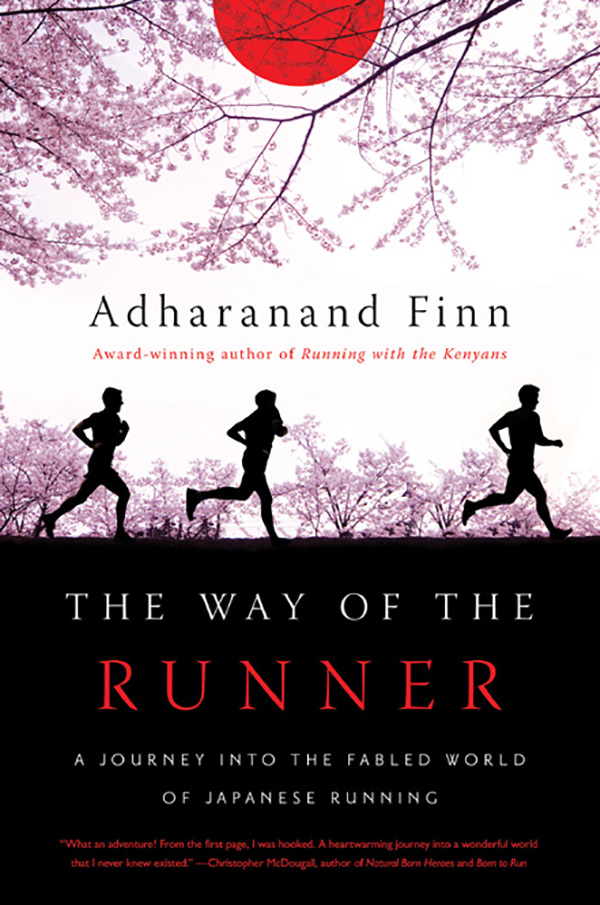

THE WAY OF THE RUNNER

Pegasus Books Ltd

148 West 37th Street, 13th Floor

New York, NY 10018

Copyright 2015 by Adharanand Finn

First Pegasus Books hardcover edition June 2016

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in whole or in part without

written permission from the publisher, except by reviewers who may quote brief excerpts in

connection with a review in a newspaper, magazine, or electronic publication; nor may any

part of this book be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form

or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or other,

without written permission from the publisher.

ISBN: 978-1-68177-121-2

ISBN 978-1-68177-184-7 (e-book)

Distributed by W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

Before enlightenment I chopped wood and carried water. After enlightenment, I chopped wood and carried water.

ZEN PROVERB

Prologue

Its February 2001. Im standing by a school wall in the small town of Hong in western Honshu, Japan. I have a hangover.

in western Honshu, Japan. I have a hangover.

The night before, my brother, who is a teacher at the school, took me straight off the plane from London, to what he referred to ominously as a naked festival. It involved drinking lots of saki, wearing nothing but a mawashi loincloth like a sumo wrestler, standing out in the freezing night with around two hundred similarly dressed men, and trying to grab hold of a long piece of cloth. As we all fought to get hold of the cloth, priests threw cold water over us. The scrum of two hundred men kicked, pulled and barged around in the dark for hours before someone finally, mercifully, emerged triumphantly with the cloth and disappeared up some steps to a shrine.

The next morning there is a picture of the melee in one of Japans national newspapers, featuring my pale backside right there in the middle. I can tell it is mine because in my dazed, drunken state I asked someone to write Flash across my back. I was thinking I was Flash Gordon, for some reason. A man on another planet wrestling his way through a scrum of men. Weve had barely four hours sleep before my brother is up again.

Im running an ekiden, he says. You want to run? I have no idea what an ekiden is, but running is the last thing on my mind that morning. I was once a keen runner, but years of working in the office of a London publishing company have left me all soft and pudgy. My running days are long behind me.

No, I say, scratching the back of my neck.

Instead he positions me by the school wall, gives me a raincoat to protect me from the drizzle, and goes off to join his team. An ekiden, it turns out, is a long-distance relay race. Every town in Japan seems to have one, and everyone gets involved in some way or another. If theyre not running, people offer to help marshal, or at the very least they come out to cheer the runners on.

I stand by the wall nodding and bowing as people bustle by under umbrellas, the race officials all wearing matching yellow raincoats. Behind me, in the school yard, everyone is gathering. I watch through the railings as athletes in shorts and singlets sprint up and down on the soggy gravel, preparing for the race. Many of them seem to be high-school students, but there are men and women of all ages taking part. They line up and then, after the bang of a starting gun, swarm off out of the school grounds and into the town.

The rain is soaking through my thin shoes, making my feet cold as I stand waiting by the empty road. The firstleg runners wear a sash called a tasuki, which they have to pass on to their team-mates further along the course, in the same way sprinters pass a baton in relays on the track. At some point the race will come back past me again, with my brother among them.

I decide to walk up and down to keep warm. Across the road an elderly couple stand under matching umbrellas, occasionally glancing up the road. Its almost an hour later before the runners come back into view, scampering down the street, people along the course calling out to them, cheering them on. My brother, when he appears, towers over everyone, all six foot four inches of him, his face flushed, the rain in his eyes, grinning to me as he lopes by.

Go on, Vinny, I shout, wishing suddenly I was out there too. It looks fun. More fun than hanging around here by this wall with my freezing hands stuck under my arms. I have an urge to throw off my jacket and start running. I get this whenever I find myself watching a race rather than running it, wondering why Im not out there too. This is such a friendly, communal event, with the whole town busily involved, that I feel left out standing here by the wall.

Its not until many years later that I get another chance to join a team and line up for an ekiden in Japan. But this time Im primed, two stone lighter and raring to go.

I enter through the revolving doors of the Tower Hotel, by the river Thames in London. Its a warm April morning just a few days before the 2013 London marathon. My legs feel strong and bouncy. Im ready to race and I can sense the quiet buzz of anticipation here at the elite athletes hotel.

Just inside the door, by a curving marble staircase, a small group of people are in discussion. I recognise one of them. Its Steve Cram, my childhood running hero. Hes older now, of course, his hair shorter, flatter than in his heyday, but the same man I used to watch on television many years ago, his yellow vest whizzing around the track in pursuit of world records. I walk on, into the lobby.

As I stand there, runners walk by. Two Kenyan women in large puffer jackets wander past, their matchstick legs looking as though they might buckle under the weight of the jackets. They speak to each other so quietly its hard to know if they are actually talking. By the reception desk, two Dutchmen with big laughs are chatting to a man in sunglasses with his hood up. Its only when I hear his voice that I realise its Mo Farah.

A lot has happened in the twelve years since I stood hungover by that school wall in Japan. Somewhere along the line I started running again. Slowly, at first. I ran my first 10K race in 47 minutes. For two years it remained my best time. But gradually I began to take things more seriously, joining a running club, heading out for longer and longer runs. Then I went to live in Kenya, to train with the great Kalenjin runners of the Rift Valley. I went partly to improve my running, but also I went on a mission to understand and unravel the mystery that surrounds these great runners. I wanted to know who they were, what they did, and what moved them. When I came back I wrote the book Running with the Kenyans: Discovering the Secrets of the Fastest People on Earth.

In a few days a battle will rage between a group of Kenyans and Ethiopians to win the most prestigious city marathon in the world. Ill be running too, somewhere among the sweating throng of people strung out along the streets behind them. Im hoping to beat my best time and run under 2 hours 50 minutes. Ive trained hard for it, eaten the right food, bought the right kit. But today, as I stand in the Tower Hotel lobby, its neither me nor the Kenyans Im interested in. Today, Im looking for the Japanese.

*

Something is going on in Japan. From the outside, its easy to miss. Virtually every big road race around the world is won by a seemingly endless succession of superfast Kenyans and Ethiopians. No one else gets a look in.

But on one small group of islands in east Asia, theyre at least putting up a fight. In 2013, the year in which our story is set, only six of the hundred fastest marathon runners in

Next page

in western Honshu, Japan. I have a hangover.

in western Honshu, Japan. I have a hangover.