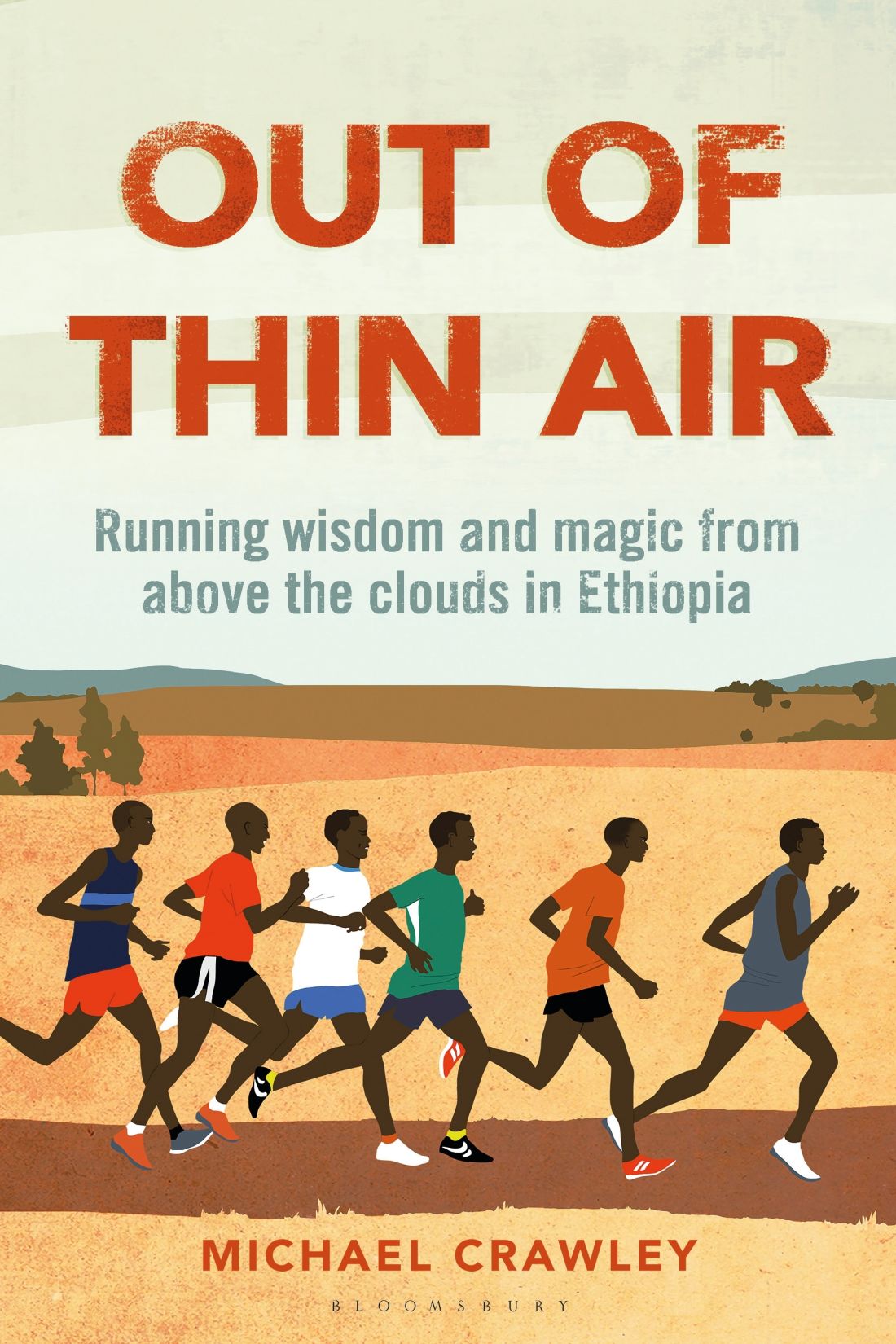

Praise for Out Of Thin Air

Through reading this book you will come to understand that the heart and soul of running are to be found in Ethiopia. I welcome everyone to experience the Ethiopian love of running, and to come and have the same life-altering experience that Michael had. Running is life!

Haile Gebrselassie, Olympic gold medal winner and World Champion

Out Of Thin Air is full of wonderful insights and lessons from a world where the ability to run is viewed as something almost mysterious and magical. With his understated writing style, Crawley gently pulls back the layers on one of the worlds most incredible sporting cultures, revealing a powerful simplicity at its core.

This is an honest portrait of Ethiopian running that doesnt shy away from the difficulties of the life there, or the hardships and insurmountable obstacles most of the runners face in their quest to find success, and the book can leave you feeling a little sad, as well as inspired. But more than anything, after reading it you will look at the great runners of Ethiopia a little differently the next time you see them streaking away majestically at the front of a major race.

Adharanand Finn, author of Running with the Kenyans

A deep dive into the rich and complex culture that produces some of the fastest runners the world has ever seen. Michael Crawleys perceptive portrait will force you to re-examine your assumptions about why those who dream even the biggest dreams sometimes succeed.

Alex Hutchinson, author of Endure

For Roslyn and Maddy

Contents

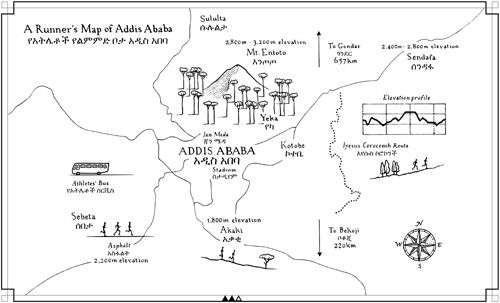

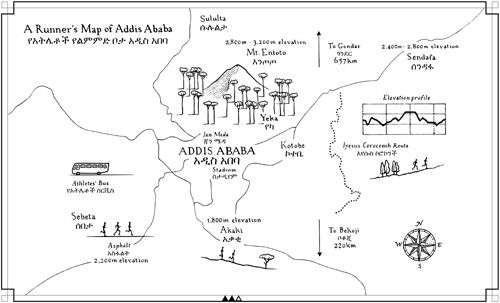

The research that forms the basis of this book was funded by a studentship from the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC), and the writing was supported by an ESRC Postdoctoral Fellowship. I am grateful for this generous support and expression of confidence in my work. Thank you to my agent Richard Pike for believing in the book, to Charlotte Croft and Zo Blanc at Bloomsbury for improving it, and to Eliza Southwood and Owen Delaney for bringing it to life with the cover illustration and map.

In Ethiopia I am deeply grateful to Benoit Gaudin and his family for making me feel welcome for longer than they perhaps first anticipated, and to Benoit in particular for fascinating conversations about running and social science on his balcony. To Mimmi Demissie for endless hours of patient Amharic tuition in the cafes of Arat Kilo. To Ed and Rekik for wonderful and caring friendship.

Thank you to Fasil, Birhanu, Tsedat, Jemal, Aseffa and the many other runners who provided hours of laughs and company in pool halls and at football matches on top of all the hours of running on the trails. To Messeret for sharing his coaching wisdom with me. Finally and especially my thanks goes to Hailye Teshome, without whom this project would not have been possible. Hailye provided introductions, translation, patient explanations, incredible cooking and endless encouragement. I hope this book does justice to the running life that he and the other runners allowed me to share with them. Through encouraging me to train alongside the runners of Moyo Sports, Malcolm Anderson gave me a window into the world of Ethiopian running that would have been almost impossible to negotiate without his support.

Thanks to my PhD supervisors in Edinburgh, Neil Thin and Jamie Cross, whose ideas and support made all the difference. Jamie had faith in this project before I did, and encouraged me to apply for the funding that made it possible. Jeevan Sharma, Elliott Oakley, Tom Boylston, Juli Huang, Nick Long, Allysa Ghose, Dan Guiness, Niko Besnier, Leo Hopkinson, Felix Stein, Declan Murray and Tom Cunningham have all been generous readers of my writing. Diego Malara was an especially attentive reader and helped me enormously. The hours we have spent discussing Ethiopia have been extremely valuable.

Back at home I thank my own coaching duo, Max and Julie Coleby. They have invested countless hours in making me a better runner, and always tolerated my tendency to ruin all the training by taking off travelling. Without their encouragement I would have abandoned competitive running years ago and this book would never have been written. Thanks to my parents, for having a house full of books and for always encouraging my international adventures.

Most of all, to Roslyn, for turning the PhD into a joint adventure, and to little Maddy who turned up halfway through the writing of the book and put the whole thing in perspective.

Photo credits: All photographs Michael Crawley except: , photograph of Tsedat used courtesy of Seville Marathon.

Most of the training and racing described in this book took place between 2015 and 2016, which is not all that long ago in the grand scheme of things. However, given the developments in footwear technology since then, in marathon-running terms it seems almost like a different era. A brief note on running times therefore seems appropriate. For the uninitiated, the recording of times in this book follows the convention of listing hours, minutes and seconds separated by a full stop. So 2.01.39 means two hours, one minute and 39 seconds.

Much of the focus in the athletics press in the last couple of years has been on shoes rather than athletes, with the perception being that people are now running significantly faster than before. This feeling was shared in Ethiopia, where excitement (and anxiety) about the potential of shoe technology was widespread. If you look at the rankings, though, the difference in speed at the top level of the sport isnt that big. The 50th ranked male marathon runner in 2015 ran 2.07.57, compared with 2.06.22 in 2019. The difference was around two minutes for women, from 2.23.30 for 50th in the rankings in 2015 to 2.25.42 in 2019. An improvement of a minute and 30 seconds to two minutes does suggest that shoes have distorted performances to an extent, but perhaps not in the astronomical way some commentators suggest.

That 50th ranked time around two hours and eight minutes for men, and two hours 25 minutes for women is the sort of time the athletes I knew had in mind when they talked about changing their lives through the sport. In 2015 it was the kind of time that would be likely to net a contract with Nike or Adidas. To put that in perspective, in parkrun terms thats a little over eight consecutive parkruns in 15.10 for men, or 17.15 for women.

When my alarm goes off at 4.40 a.m. I have already been awake for six or seven minutes. The familiar wail has already crackled from the churchs speakers, our dog has been barking at hyenas all night and I always find it difficult to sleep knowing I have to be up so early. Im already wearing my running shorts and I stumble into the rest of my kit, laid out the night before to make things as simple as possible at this hour. Five minutes later Hailye and Fasil knock on my door. Hoods up against the cold, we head down to the team bus. Are you tired? I ask Fasil in Amharic. I am not tired! he exclaims, grinning. It is extremely rare for Fasil to admit to being tired. The number of people in the pitch-black street surprises me. The Amharic word for dawn is goh and people tend to start their day as though this has been shouted, loudly, in their ear. Already men stride purposefully through the dust and groups of people wait for the minibuses that head for the town centre. These minibuses start around 4 a.m. and the familiar shout of the potential destinations, Piazza, Arat Kilo ! can already be heard. A kid in a faded Arsenal shirt leans out of the door of one of them and tries out his English. Where are you go? he says. Entoto, I tell him, as he vanishes into the darkness.