Copyright Zack Davisson, 2015

All rights reserved

ISBN 978-09887693-4-2

First (1) edition

A Chin Music Press original

Chin Music Press

1501 Pike Place #329

Seattle, WA 98101

USA

www.chinmusicpress.com

Book design by Carla Girard

Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication data is available.

To my wonderful wife, Miyuki Davisson.

And to Oiwa, Otsuyu, and Okiku.

Please dont hurt me.

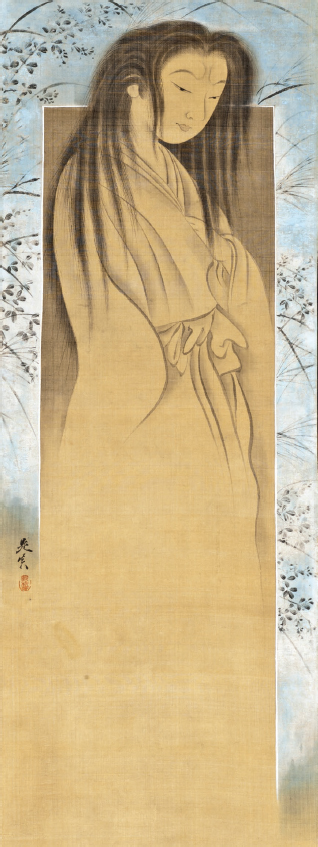

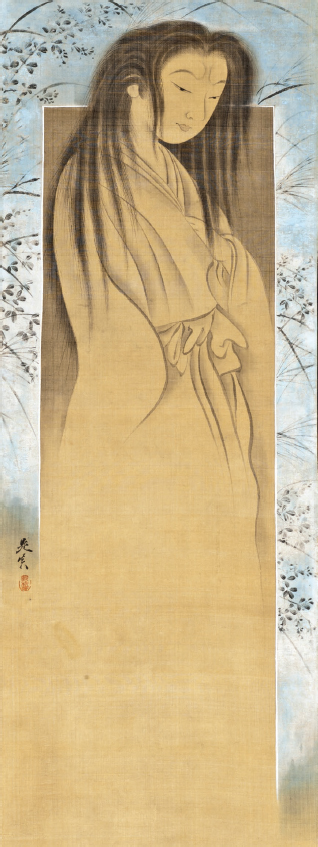

A portrait of death, painted from life.

Maruyama Okyos painting of his lost love

Oyuki is the one that started it all.

Ghost of Oyuki, Maruyama kyo

Ghost, Shibata Zeshin

Okyos ghostly portrait of Oyuki had many imitators, such as this painting by Shibata Zeshin.

From Yoshitoshis New Forms of 36 Plays, a shin kabuki play that dramatizes ghostly revenge.

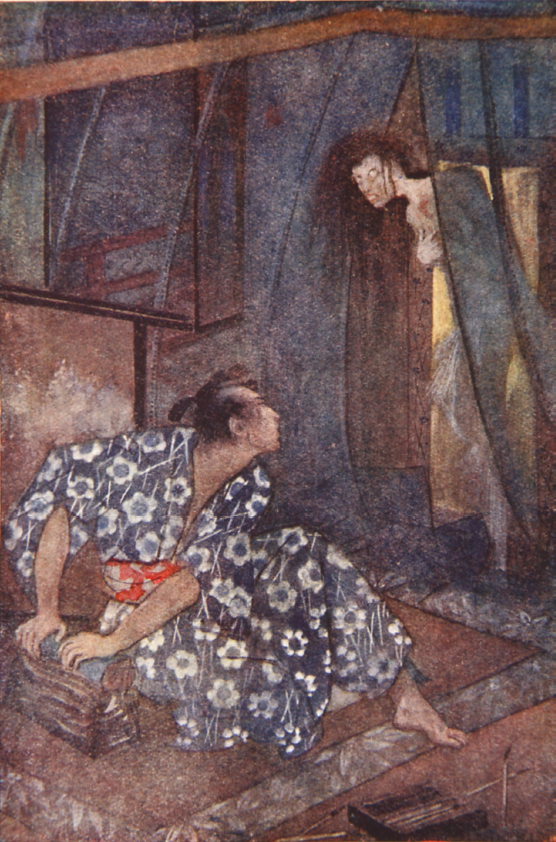

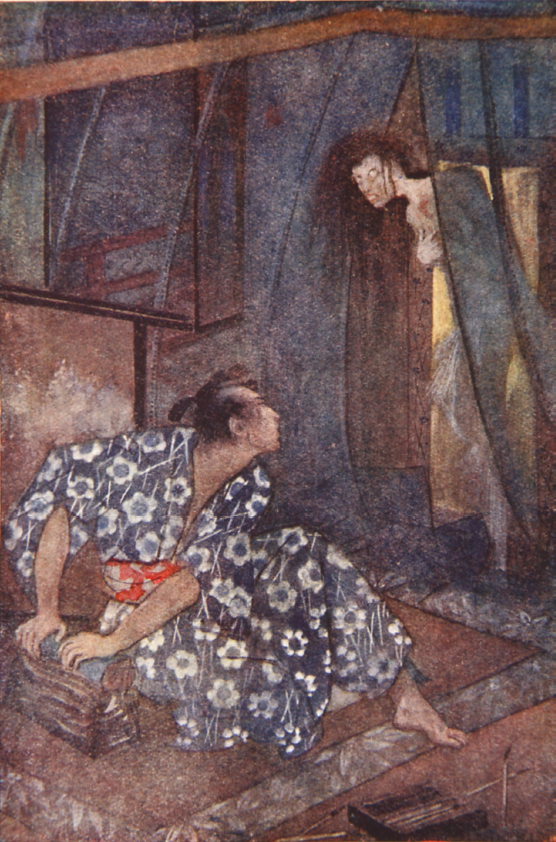

Kimi Finds Peace, Evelyn Paul

An artist, Sawara, is haunted by the yrei of his pupil Kimi who died with her love unfulfilled. An illustration from F. Hadland Davis 1918 The Myths & Legends of Japan, this is one of the first images of a yrei by a Western artist.

The Ghost of Kohada Koheiji, Tsukioka Yoshitoshi

Kohada Koheiji was a kabuki actor so adept at yrei roles that he became a yrei himself. This is a classic picture of that famous kabuki spirit.

Maruyama kyo, Tsukioka Yoshitoshi

Yoshitoshi imagines the manifestation of The Ghost of Oyuki, as Maruyama kyos ghostly lover emerges directly from the painting.

Ghost Appearing to a Warrior, Utagawa Kunisada

A ghostly scene from a kabuki play. These were sold as souvenirs, featuring popular actors in their roles.

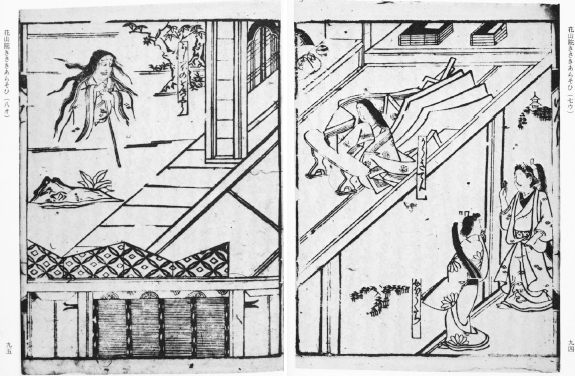

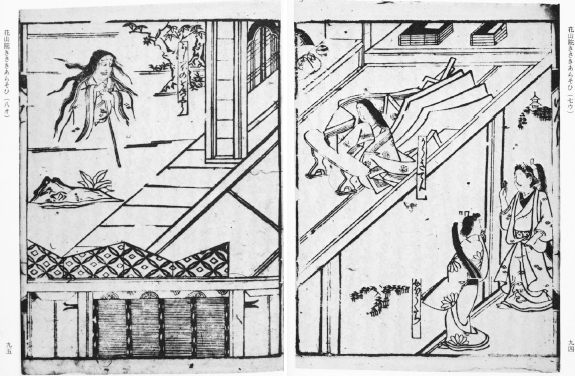

The Quarrel with the Queen at Kasano Temple, Artist unknown

From 1673, this picture book of the puppet play, Kasannoin Kisakiarasou, is the oldest known image of an ashinonai yrei a footless yrei.

Introduction

GHOSTS AND YREI

I lived in a haunted apartment.

Several years back, my wife and I lived in Ikeda, a small, suburban city eighteen minutes by train outside of the massive industrial metropolis of Osaka, Japan. Ikeda was a nice place: not too rural, not too urban, with a zoo, some good restaurants, and a museum dedicated to instant ramen. We had lived in the same apartment for about two years. Then, trying to save money during our last year in Japan, we moved into a cheaper place.

Kishigami Bunka, the name of our new apartment, was an old, two-story wooden ramshamble building built sometime in the 1920s. It was a dusty, run-down place called a cultural apartment due to its old-style of living, including woven tatami mat flooring and lack of hot running water, not to mention the tiny trough that passed for a toilet. The rent was absurdly cheap only 20,000 yen, around $180 a month. Our previous apartment in Ikeda, of equal size and quality, had been 60,000 yen.

I thought we were getting a bargain.

But Kishigami Bunka had an odd atmosphere, something sensed by almost every visitor. It just felt weird. The unease wasnt helped by the strange red marks all over the ceiling, almost like a small childs hand and footprints. The marks didnt want to wash off no matter how much we scrubbed. We even tried bleach. And then there were the unusual bumps and noises, especially the ones coming from the kitchen wall. Stranger still was the door in the living room that led to nowhere. My wife and I had been commanded by the landlord to Never open that door! He gave no reason for this, offered no explanation. And, unlike foolish people in horror movies, we did as we were told.

For the seven months that we lived in Kishigami Bunka, we never opened the door.

There were few outright scares other than brief glimpses out of the corner of our eyes and the sometimes overwhelming sensation that we were not alone in a particular room. We had hung a large, black, patterned tapestry over the mystery door neither of us wanted to be reminded of it. And we took to turning our mirrors towards the wall at night due to an inexplicable but unavoidable feeling that looking in the mirrors in the dark was a Very Bad Idea.

The worst event happened one night when my wife had a horrible dream. So vivid was the dream that she woke me up screaming. As I shook her awake, it took several minutes to convince her that what she had seen wasnt really happening. She had dreamed that the red handprints on the ceiling had stretched and extended down to grab her from our futon, and that she was being slowly dragged up to a giant sucking black hole in the ceiling from which she would never emerge. She believes to this day that I must have plucked her out of mid-air and saved her life.

Maybe it was just our nerves and imagination, but there was an unmistakable something to the place. Our Japanese visitors had no problem putting a name to it. Soon upon entering Kishigami Bunka, they would sense the vibes of the place, look around a bit and inevitably say Ahhh yrei ga deteru There is a yrei here.

I found out later that the haunting was the reason for the ridiculously low rent. Nobody wanted to live in Kishigami Bunka. The apartment had been vacant for years.

Kishigami Bunka was not my first yrei. Long before sharing a home with one in my cultural apartment, I had met yrei in a large, hardcover book about ghosts.

When I was in elementary school, I had been fascinated with folklore and the supernatural. My mother bought me a series of books from Time-Life called The Enchanted World, which included a volume on ghosts. Inside was a Japanese ghost story called The Wifes Revenge. Illustrated with old ukiyo-e prints, the story showed figures identified as Japanese ghosts. But they didnt look anything like my idea of ghosts. The wild black hair, hanging white robes, and exaggerated facial features went against my ingrained cultural concepts of ghosts and were thus more disturbing. One particular image stuck in my head: a woman whose face dripped like melting candle wax as she floated down from a burning lantern.

I know now, many years later, that this picture was Oiwa Emerging from the Lantern by the Edo period artist Utagawa Kuniyoshi. Oiwa, from the ghost story Tkaid Yotsuya Kaidan,