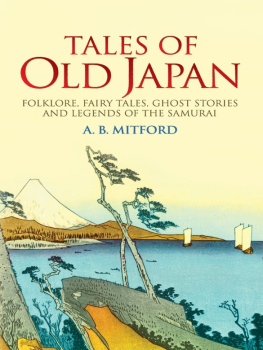

JAPANESE

LEGENDS AND FOLKLORE

Samurai Tales, Ghost Stories, Legends, Fairy Tales, Myths and Historical Accounts

A.B. MITFORD

With a new foreword byMichael Dylan Foster

FOREWORD

W hen A.B. Mitfords Japanese Legends and Folklore, originally titled Tales of Old Japan, was published in Britain in 1871, a reviewer for The Times wrote we do not venture too high praise when we say that a strange country and people have never been the theme of a more entertaining and informing work. Not only do these comments reflect the position of Japan in the Victorian imaginationas a strange country and peoplebut they also reflect a popular desire for understanding a faraway place that was experiencing unparalleled transformations in political, economic and cultural realms. Mitfords work recounted tales of old Japan because a new Japan was emerging.

During the long Edo period (16031868) a succession of military leaders known as shoguns ran the country, overseeing a hierarchical society divided into four major classes, with Samurai (less than ten percent of the population) positioned at the top. Because the Shogunate imposed strict limitations on economic and cultural exchange with other countries, Edo-period Japan was a world unto itself, relatively isolated from outside influences and ideas. But all this started to change in 1853, when Commodore Matthew C. Perry of the United States Navy sailed into Edo Bay with a small squadron of black ships and demanded that Japan open its ports. In the decade and a half that followed, continued pressure from the U.S. and other Western powers, combined with weakening domestic leadership, brought about the collapse of the Shogunate and the birth of a new government. The 1868 Meiji Restoration marked the beginning of Japans experiment with modernity and its emergence globally in economic, cultural, political andall too soonmilitary arenas.

As the Second Secretary of the British Legation from 18661870, A.B. Mitford participated in many of the critical diplomatic negotiations of these momentous years. He met with shoguns and regional lords, and he was among the first Westerners ever to have a personal audience with the new Meiji Emperor. He did this all before the age of thirty-five.

Indeed, Algernon Bertram Mitford (18371916) led an extraordinary life. Bertie, as he was called, was born into an English aristocratic family but spent his early years in Germany and France. His parents were divorced, something exceedingly rare at the time, and young Mitford was sent to Eton at the age of nine. He went on to Oxford and would eventually join the Foreign Office, where his father had also served for a short period. He was posted briefly to Russia, and next to Beijing, where he eagerly explored Chinese culture and gained an excellent understanding of the language.

From China, Mitford was sent to Japan in October of 1866 to work under Sir Harry Parkes (18281885), Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary. There he also became close friends with Ernest Satow (18431929), who would go on to become a renowned scholar, diplomat, and Japan expert. During the waning days of the Shogunate, Japan was not a safe place for Western government officials, and Mitford experienced his share of adventures, including assassination attempts and military skirmishes, as well as storm, fire, and a near drowning. As he recalled many years later, For nearly four years I never wrote a note without having a revolver on the table, and never went to bed without a Spencer rifle and bayonet at my hand.

Mitford applied himself diligently to the study of the Japanese language, achieving an extraordinary level of proficiency. Even while pursuing his diplomatic duties, he gathered and translated materials for the present book, which he completed after his return to England and sold to a publishing house for only 240 pounds. It was as much as they could be expected to give in the circumstances, he explained in his autobiography Memories, for the subject and I were both new, and it was impossible to say whether we should catch the fancy of the public. But catch the fancy of the public they both did, especially with the books publication coinciding with Japans emergence into the European consciousness. The Times praised the work as far more valuable than any mere record of personal adventure could possibly be, for it shows us Japanese life and manners, not only as they are seen by foreign eyes, but as they are depicted in the literature of the country itself. Indeed, despite Mitfords own exciting experiences in Japan, his book was not autobiographical but rather an earnest attempt to introduce Japan from an insiders perspective.

So what are the contents? In many ways, the work is a hodgepodgethe word tales interpreted rather openly to include translations of Edo-period literary texts, popular folktales for children, supernatural legends and Buddhist sermons. In some cases, Mitford also adds detailed introductions and notes concerning tradition, literature, theater, and history. Most famously perhaps, the appendix contains his own eyewitness account of ritual suicide or hara-kiri.

The book begins with a telling of the story of The Forty-Seven Rnins, an early eighteenth-century historical vendetta that had been recounted and reinvented throughout the second half of the Edo period in written, visual and performance traditions including bunraku puppet theater and kabuki drama. Today this legend of loyalty and revenge is well-known even in the Westmost notoriously reinterpreted in 2013 as a film with Keanu Reeves! All this makes Mitfords historical account even more compelling: his is the first detailed retelling ever rendered into English and was, for many years, considered an authoritative version.

Another important first is Mitfords inclusion of Fairy Tales, most of which he translates from little separate pamphlets, with illustrations, the stereotype blocks of which have become so worn that the print is hardly legible. These storieslike The Tongue-Cut Sparrow, The Crackling Mountain or The Adventures of Little Peach Boyare classic Japanese folktales that would have been well known by children and adults alike, and are still popular today. He also translates a number of supernatural legends, under the heading Concerning Certain Superstitions, recounting the mischievous machinations of cats, foxes, and badgers (by which he means tanuki or raccoon dogs). Such creatures are quintessential examples of the fantastic shapeshifting ykai or bakemono of Japanese folklore that were exceedingly popular in Edo-period culturein everything from kabuki to woodblock prints to ghost story collections to board gamesand are still refashioned today in popular media such as manga, anime, films, and video games.

Mitfords emphasis on folklore rather than classical or pure literature reflects his belief that no better means could be chosen of preserving a record of a curious and fast disappearing civilization, than the translation of some of the most interesting national legends and histories. His translation of folkloric material also dovetails with the burgeoning field of folklore studies in his native Britain. It is no coincidence that in 1871, the same year Mitford published this book, Edward B. Tylor (18321917), one of the founding figures of anthropology, published his seminal work Primitive Culture. In 1872 Scottish folklorist and scholar Andrew Lang (18441912) published Ballads and Lyrics of Old France, and 1878 saw the founding of the Folklore Society in London. In other words, popular interest in Mitfords work reflected excitement about Japan as well as a burgeoning appreciation of folklore and oral tradition as a window into people and culture. A scholarly interest in folklore would also take hold in Japan, but not until the work of Yanagita Kunio (18751962) and others in the early twentieth century. Mitfords conscious efforts to collect and publish folktales and legends not only prefigured many domestic Japanese endeavors but were also a precursor of the work of more famous Western interpreters, such as Lafcadio Hearn (18501904) and Basil Hall Chamberlain (18501935).

Next page