THESE tales and legends have been collected from many sources. Some of them have been selected from the Ko-ji-ki, or Record of Ancient Matters, which contains the mythology of Japan. Many are told from memory, being relics of childish days, originally heard from the lips of a school-fellow or a nurse. Certain of them, again, form favourite subjects for representation upon the Japanese stage. A number of the stories now gathered together have been translated into English long ere this, and have appeared in this country in one form or another; others are probably new to an English public.

Thanks are due to Marcus B. Huish, Esq., who has allowed his story, The Espousal of the Rats Daughter, to be included in this collection.

Green Willow

T omodata, the young samurai, owed allegiance to the Lord of Noto. He was a soldier, a courtier, and a poet. He had a sweet voice and a beautiful face, a noble form and a very winning address. He was a graceful dancer, and excelled in every manly sport. He was wealthy and generous and kind. He was beloved by rich and by poor.

Now his daimyo, the Lord of Noto, wanted a man to undertake a mission of trust. He chose Tomodata, and called him to his presence.

Are you loyal? said the daimyo .

My lord, you know it, answered Tomodata.

Do you love me, then? asked the daimyo .

Ay, my good lord, said Tomodata, kneeling before him.

Then carry my message, said the daimyo. Ride and do not spare your beast. Ride straight, and fear not the mountains nor the enemies country. Stay not for storm nor any other thing. Lose your life; but betray not your trust. Above all, do not look any maid between the eyes. Ride, and bring me word again quickly.

Thus spoke the Lord of Noto.

So Tomodata got him to horse, and away he rode upon his quest. Obedient to his lords commands, he spared not his good beast. He rode straight, and was not afraid of the steep mountain passes nor of the enemies country. Ere he had been three days upon the road the autumn tempest burst, for it was the ninth month. Down poured the rain in a torrent. Tomodata bowed his head and rode on. The wind howled in the pine-treebranches. It blew a typhoon. The good horse trembled and could scarcely keep its feet, but Tomodata spoke to it and urged it on. His own cloak he drew close about him and held it so that it might not blow away, and in this wise he rode on.

The fierce storm swept away many a familiar landmark of the road, and buffeted the samurai so that he became weary almost to fainting. Noontide was as dark as twilight, twilight was as dark as night, and when night fell it was as black as the night of Yomi, where lost souls wander and cry. By this time Tomodata had lost his way in a wild, lonely place, where, as it seemed to him, no human soul inhabited. His horse could carry him no longer, and he wandered on foot through bogs and marshes, through rocky and thorny tracks, until he fell into deep despair.

Alack! he cried, must I die in this wilderness and the quest of the Lord of Noto be unfulfilled?

At this moment the great winds blew away the clouds of the sky, so that the moon shone very brightly forth, and by the sudden light Tomodata saw a little hill on his right hand. Upon the hill was a small thatched cottage, and before the cottage grew three green weeping-willow trees.

Now, indeed, the gods be thanked! said Tomodata, and he climbed the hill in no time. Light shone from the chinks of the cottage door, and smoke curled out of a hole in the roof. The three willow trees swayed and flung out their green streamers in the wind. Tomodata threw his horses rein over a branch of one of them, and called for admittance to the longed-for shelter.

At once the cottage door was opened by an old woman, very poorly but neatly clad.

Who rides abroad upon such a night? she asked, and what wills he here?

I am a weary traveller, lost and benighted upon your lonely moor. My name is Tomodata. I am a samurai in the service of the Lord of Noto, upon whose business I ride. Show me hospitality for the love of the gods. I crave food and shelter for myself and my horse.

As the young man stood speaking the water streamed from his garments. He reeled a little, and put out a hand to hold on by the side-post of the door.

Come in, come in, young sir! cried the old woman, full of pity. Come in to the warm fire. You are very welcome. We have but coarse fare to offer, but it shall be set before you with great good-will. As to your horse, I see you have delivered him to my daughter; he is in good hands.

At this Tomodata turned sharply round. Just behind him, in the dim light, stood a very young girl with the horses rein thrown over her arm. Her garments were blown about and her long loose hair streamed out upon the wind. The samurai wondered how she had come there. Then the old woman drew him into the cottage and shut the door. Before the fire sat the good man of the house, and the two old people did the very best they could for Tomodata. They gave him dry garments, comforted him with hot rice wine, and quickly prepared a good supper for him.

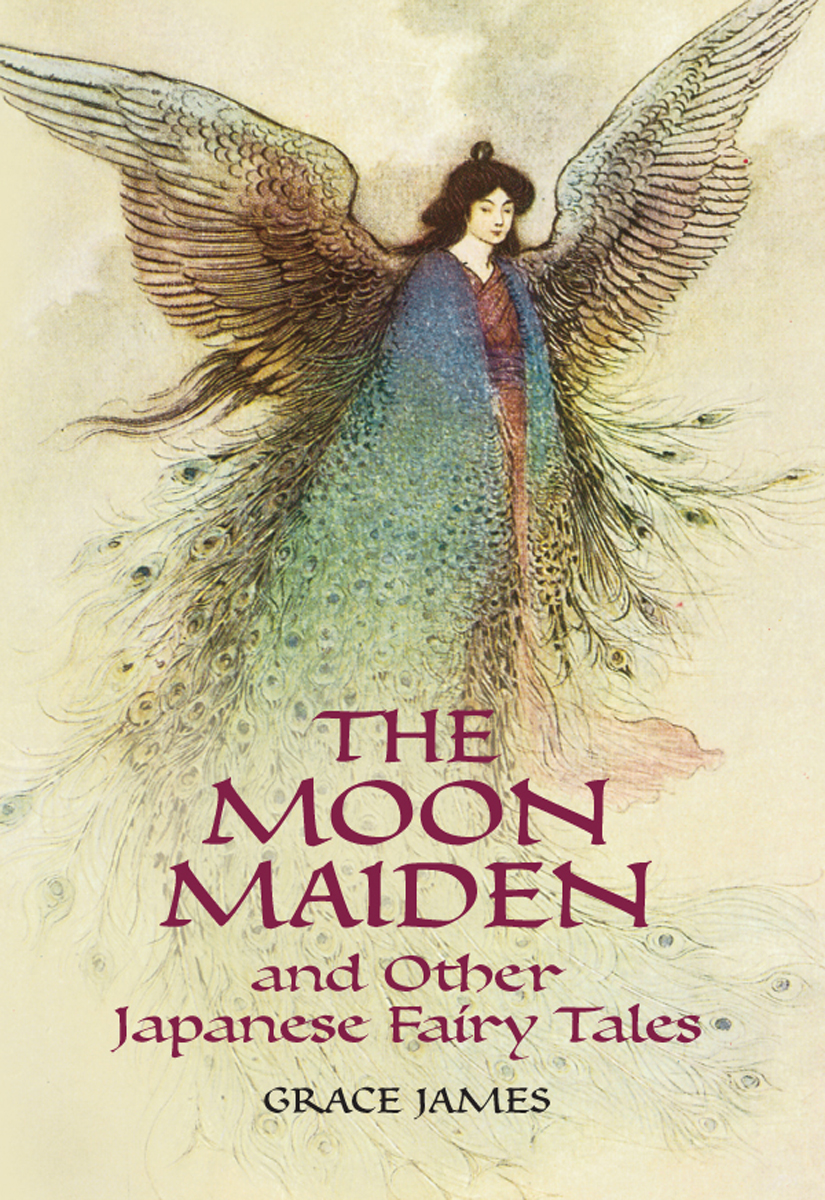

Presently the daughter of the house came in, and retired behind a screen to comb her hair and to dress afresh. Then she came forth to wait upon him. She wore a blue robe of homespun cotton. Her feet were bare. Her hair was not tied nor confined in any way, but lay along her smooth cheeks, and hung, straight and long and black, to her very knees. She was slender and graceful. Tomodata judged her to be about fifteen years old, and knew well that she was the fairest maiden he had ever seen.

At length she knelt at his side to pour wine into his cup. She held the wine-bottle in two hands and bent her head. Tomodata turned to look at her. When she had made an end of pouring the wine and had set down the bottle, their glances met, and Tomodata looked at her full between the eyes, for he forgot altogether the warning of his daimyo, the Lord of Noto.

Maiden, he said, what is your name?

She answered: They call me the Green Willow.

The dearest name on earth, he said, and again he looked her between the eyes. And because he looked so long her face grew rosy red, from chin to forehead, and though she smiled her eyes filled with tears.

Miss Etsuko Kato

Miss Etsuko Kato