Q UILT CHIN HIGH on a Sunday night, by the light of his bedside lamp, my young son asks, Was that the weekend?

Yes, it was, I reply.

But it didnt feel like a weekend, he says, employing his rip-off voice, the one reserved for bad trades in baseball and empty cereal boxes.

At twelve, he poses this question many Sundaysits a macabre family traditionthereby prompting a review of my own weekend, which frequently looks something like this: hockey; work email; groceries; an ensuing onslaught of emails about the first email; homework help; hockey; dog wrangling; family dinner; cleanup; laundry; work reading. To keep Sunday distinguishable from Saturday, I might top off the above with some light toilet cleaning. We do change it up in summer, however: the kids play soccer instead of hockey.

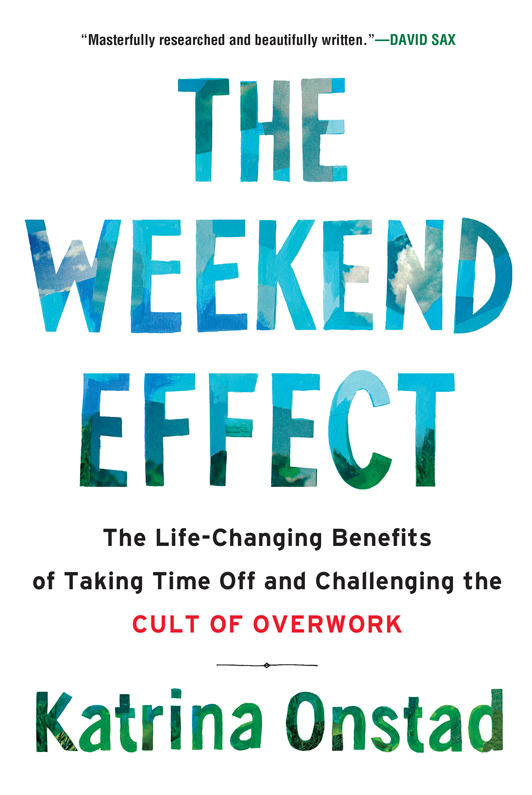

For many of todays (gratefully) employed, the workweek has no clear beginning or end. The digital age imagined by science fiction is upon us, yet were lacking robot butlers and the three-day workweek that economist John Maynard Keynes predicted in 1928. Working more than we did a decade ago is the norm for most employees, and those devices designed to liberate our time merely snatch it back. The weekend has become an extension of the workweek, which means, by definition, its not a weekend at all. Many Americans work longer hours today than a generation ago, and most work hundreds of hours more per year than their counterparts in European Union countries of similar economic status. A 2014 paper from the U.S. National Bureau of Economic Research reports that 29 percent of Americans log hours on the weekend, compared to less than 10 percent of Spanish workers. If the Spanish are too life-loving to bring home the hurt in that statistic, heres another one: even fewer of the diligent Germans work on the weekend, at 22 percent. U.K. workers are the exception among Europeans, racking up almost as many hours on weekends as Americans. They call this, unflatteringly, the American disease.

I recognize this disease. Years ago, for a brief, not-so-fun time, I was an au pair. Mostly, I was shuffling through the post-college years, hiding in a small village on a windswept shore of northern France for a few months. Every Sunday, as far as I could tell, France shut down. There was no work. There wasand this shocked my North American mall rat selfno shopping. Instead, there was The Visit and The Activity. Three kids in tow, my single-mom boss and I visited grandparents, or brought flowers to a family friend in a nursing home. Some weekends, neighbors came to the house unannounced, and food and conversation would stretch into the night. There was always an outing: a hike along the beach shore; a bike ride; a stroll through the streets of a nearby village, peering in the windows of closed shops. We could look, but not buy. These weekend days felt like ritual, embedded in the culture; something sacred. Time seemed to slow itself. These were weekends of the imagination, rich with experience, a clean break from what came before and what would come next, on Monday.

Now, with my own kids and a job as a writer that leaks across the days, my Saturday often feels hardly different from a Wednesday. Sometimes, in fact, Saturday feels busier. On weekends, Im always responding to the e-needs of clients and sources, even when technically off duty. But whos off duty, ever? Ive attended soccer games where parents are on iPads between perfunctory cheers. TGIM, jokes a friend at Monday morning drop-off, gratefully exchanging the childrens myriad playdates and activities for the relative calm of an office.

This borderless work life is no longer just a freelancers reality, or the domain of high-billing lawyers and Silicon Valley creative-class innovators. Post-recession, work means a patchwork of part-time gigs for many people, with no set pattern to the week. Millennials tend their brands around the edges of precarious work. My husband is a teacher, and he spends his nights and weekends managing emails from anxious parents and students, then scrambling back to his analog duties like marking and lesson planning. Its like were all doctors now, forever on call, I tell him, leaning in the doorway late at night, taking in the familiar sight of his back turned to me as he punches away at the computer. Really low-stakes doctors.

Too many weekends, The Activity is deferred. The Visit is deferred. Pleasure and contemplation are deferred. Sunday night is the new Monday morning, a headline in The Boston Globe trumpets, noting that many workers are getting a jump on Monday morning emails by spending Sunday night in the Inbox. The executive recruiter and the venture capitalist interviewed for the article sheepishly give what amounts to the same reason for ceding their Sunday night: Since everyone else is doing it, Id better do it, too. No one wants to be left behind, and so we are running, scurrying, our days streaming past.

For this blatant neglect of leisure, Aristotle would be mad at us. In Aristotle, leisure isnt just the time beyond paid work. Its not mindless diversion or choresa binge-watch weekend or a closet overhaul. Leisure is a necessity of a civilized existence. Leisure is a time of reflection, contemplation, and thought, away from servile obligations. But today, leisure smells lazy, a word connoting uselessness and privilege. Somewhere along the line, the joyless Protestant ethos became a reality, if not a mantra: Live to work, not Work to live. To understand how sullied the idea of leisure has become, look no farther than the leisure suita louche fashion-crime, hopelessly out of date.

I offer feeble comfort to my son. But I feel it, too: something missing; a profound absence altering body and soul. I remember my own child self anticipating the weekend on Friday morning, the great expanse of possibility before me. My parents friends, and my friends, would fill the house. Bad TV was waiting to be consumed in the early-morning shadows. Mostly, I remember being bored, and in that boredom picking up a pen and paper, and discovering that writing felt better than any sport Id tried or picture Id drawn. Time wasnt tight, but roomy, a space to explore.

These moments of vivid weekend experience are fewer now, and not only because Im older, and farther from wonder. My time is bleeding out, and my days and nights are consumed by work and an endless chain of domestic pursuits that leave me snappish and unfamiliar to myself. In a 2013 survey, 81 percent of American respondents said they get the Sunday night blues. Surely this melancholy isnt just about anticipating the workweek ahead, but about grieving the missed opportunity behindanother lost weekend.

After too many Sunday nights turning off the light in my kids rooms with an apology for the lameness of the previous two days, thereafter collapsing in exhaustion, I decided to dig deep into the weekend problem: how we lost it, and what it means to live without it. When I started investigating, two things became clear: Im not alone with my Sunday night letdown, and smarter people than I are fighting to preserve the weekendand winning. I talked to people who fiercely protect their weekends for the things they love. There are CEOs who are reinventing the workweek to spend time with their families, and successful corporations that are beginning to offer four-day workweeks, and companies that now ask their employees to drop their phones off on Friday night and pick them up on Monday. Shonda Rhimes, the ridiculously prolific and successful writer-producer-showrunner behind hit shows like