David Marr asserts his right to be known as the author of this work.

All Rights Reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means electronic,

prior consent of the publishers.

A Cataloguing-in-Publication entry is available from the National Library of Australia

Wonderful, Wonderful

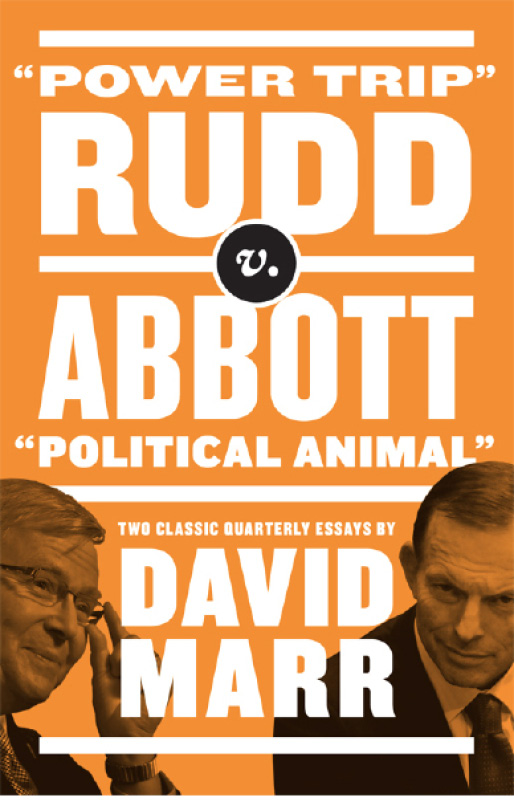

Those Chinese fuckers are trying to rat-fuck us, declared Kevin Rudd. As snow fell on Copenhagen on its palaces and squats, on police and their dogs, on protesters rugged up against the fierce cold and on the big, bland Bella Center where the largest gathering of world leaders in history sulked and plotted the prime minister of Australia faced the collapse of old dreams. This was the little boy fascinated by China, the kid who longed to be a diplomat, the man who believed a better world might be built through international agreement, and a prime minister struggling to meet one of the greatest moral, economic and environmental challenges of our age. Life had brought him, inevitably it seemed, to this icy Scandinavian city a few days before Christmas 2009 and he blamed the Chinese for wrecking it all.

The Copenhagen that mattered began on 17 December and lasted forty hours. Rudd slept for one of them. He wasnt shy. He relished working with the big boys. Almost to the very end he was a player in the meetings that mattered. He began the last long haul working with Gordon Brown to try to persuade low-lying states like Kiribati and the Maldives to let the world warm a little more than 1.5 degrees. Mid-morning saw him deliver his set speech to the full plenary in the big hall. It was superior Rudd pared down, not too much jargon, only a little mawkish about Gracie:

Before I left Australia, I was presented with a book of handwritten letters from a group of six-year-olds. One of the letters is from Gracie. Gracie is six. Hi, she wrote. My name is Gracie. How old are you? Gracie continues, I am writing to you because I want you all to be strong in Copenhagen. Please listen to us as it is our future. I fear that at this conference, we are on the verge of letting little Gracie down.

Australians with sharp ears might have picked the trademark boast that Rudd had done his homework: If you examine, as I have done, the 102 square bracketed areas of disagreement that lie in the existing text before us

After Queen Margrethes state dinner at the Christiansborg Palace Rudd so monopolised Princess Marys attentions that the British prime minister on her other side was left staring at his plate he joined Nicolas Sarkozy, Angela Merkel, Brown and another twenty world leaders in freewheeling and futile efforts to find agreement. At 3 a.m. they left the haggling to their environment ministers. By this time delegates were sleeping on sofas all over the Bella Center. Rudd had an hours kip in an armchair, all he felt he needed to keep going.

Barack Obama jetted into the city that morning and joined the talks. The United States was offering little in the way of emissions cuts but wanted what the president called accountability. Without any accountability, any agreement would be empty words on a page, Obama told the delegates. Absent was Wen Jiabao. The snub was deliberate. Rudd believed the Chinese were intent on sabotaging any deal that involved binding obligations and international monitoring.

Tired and exasperated, surrounded by a knot of Australian officials and press, Rudd began to rage against the Chinese. He needed sleep. His anger was real, but his language seemed forced, deliberately foul. In this mood, hed been talking about countries rat-fucking each other for days. Was a deal still possible, asked one of the Australians. Depends whether those rat-fucking Chinese want to fuck us.

Obama postponed his departure a few hours. At nightfall on an already endless day, the leaders of the twenty-six nations met again, with Wen Jiabao once more pointedly absent. The Guardian s Mark Lynas reported the Chinese blocking every initiative:

Why cant we even mention our own targets? demanded a furious Angela Merkel. Australias prime minister, Kevin Rudd, was annoyed enough to bang his microphone.

The bones of the Copenhagen Accord were decided that evening in a meeting between the US, China, India, Brazil and South Africa. Rudd was not there. The leaders agreed to vague targets, no monitoring and more gatherings down the track. This bare deal was sent on to Rudds group of leaders. Meanwhile Obama briefed the US press and flew out on Air Force One . When Rudd emerged an hour later, he had to be told the world already knew the outcome. Addressing reporters with barely the energy to take notes, he declared bravely: We prevailed. Some will be disappointed by the amount of progress. The alternative was, frankly, catastrophic collapse of these negotiations.

His efforts at Copenhagen are Rudds answer to those who accuse him of being a bureaucrat at heart, an incrementalist, a leader unable to dream. He sees Copenhagen as proof that hes willing to go out on a limb, spend political capital and court trouble at home for a great cause. And Rudd insists Copenhagen was not a failure. He is one of an unusual species: the diplomat turned leader. Though his time in the foreign service was a brief seven years, theyve marked him for life. For the diplomat, negotiations have never failed so long as theres a prospect, however vague, of agreement somewhere down the track. For someone who thinks as he does, it can be just as important to keep everyone at the table, to keep talks going, to keep hopes alive, as it is to bring great issues to a head. The rhetoric of success Rudd used in these exhausted hours wasnt all spin. It was authentic Rudd.

That he was still on his feet seemed a miracle. This least athletic of men has deep emotional and physical resilience. His climate-change minister, Penny Wong, was dead on her feet. Rudd seemed unaware of this. He was taken aside and urged to get her out of there, to get her to her hotel. Wong found a shower somewhere and stayed on for the last session. Later that morning Copenhagen came to a formal end, with the parties merely noting the vague deal brokered by Obama and Wen Jiabao.

Rudds bond with the people began to fray after Copenhagen. Having picked him as a leader long before he became his partys choice, Australians had held Rudd in extraordinary affection for years. Never had the polls shown a prime minister so popular for so long. But after this debacle the mood shifted. Malcolm Turnbull had fallen. His place as leader of the Opposition was taken by a Tory head-kicker unembarrassed to embrace the denialists cause. The old consensus on climate change, which Rudd had identified himself with so closely, began to melt away. In April 2010 when he abandoned his emissions trading scheme until the far reaches of a second term, the people and the polls turned on him savagely. His leadership was in question. Rudd had sold himself to the Australian people as a new kind of leader: a man of intellect and values out to reshape the future. If he isnt that, people are asking, what is he? And who is he? Rudd seems to have been with us forever yet still be a newcomer, indeed a stranger, in the Lodge. Millions of words have been written about him since he emerged from the Labor pack half-a-dozen years ago, but Rudd remains hidden in full view.