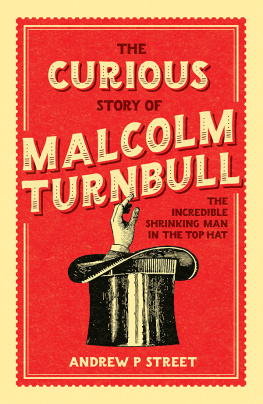

Look, I never meant to write about politics.

That I do at all is largely the fault of Marcus Teague, then deputy editor at TheVine.com.au, who invited me to take over the sites 10 Things column in 2012 and didnt bat an eyelid as it stopped being about wacky internet memes and instead became largely a snarky rant about the state of Australian politics.

So this is effectively his fault, really, and also the fault of Alyx Gorman, Jenna Clarke, Anna Horan and Jake Cleland, who oversaw editorial matters at various points during my tenure. And of Time Out Sydney, especially Nick Dent, who let me drift from music and comedy into my growing obsession with parliament.

Fairfax and The Sydney Morning Herald is even more responsible since they then gave me the View from the Street column and allowed me to rant regularly to the entire nation. Thank you Judith Whelan, Conal Hanna, Georgia Waters and the industrious night editors and social media team who get the thing out there five evenings a week.

My editors at Allen & Unwin are the most to blame of all, though, for inviting me to write a book in the first place. The charming and erudite Richard Walsh is a champion of a human beingnot least for talking me into this and then talking me down after realising for what Id very literally signed up. The unflappable and kind Rebecca Kaiser guided this thing from manuscript to print and answered a lot of very stupid questions along the way, and comprehensive thanks are due to copy editor Ali Lavau, who fixed my typos and accurately pointed out that there are certain words I really do use a lot. Like, a lot.

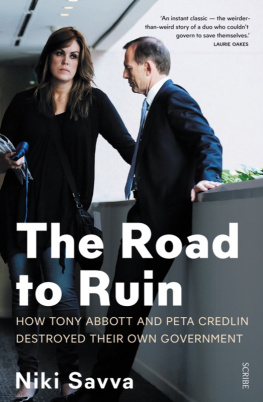

Thanks are also due to two of my former Time Out colleagues: Daniel Boud, who shot the misleadingly handsome author photo of me, and Robert Polmear, who did the awesome cover. Gentlemen both.

I owe a lot of people a lot of drinks for either giving advice, reading bits of this thing as it rapidly congealed, or just telling me that it was all going to be OK. Particular thanks to Marc Fennell, who talked me into taking the meeting about this in the first place and gave excellent advice when I accurately said sure, but I have no idea how to write a book.

Thanks to my sprawling and multitudinous family for their love, support and intuitive sense of when to ask so, hows the book going? and when to change the subject.

Thanks also to the many cafes of Sydneys inner west, where I discovered that the stereotype of the jerk with a MacBook, slamming coffee and tapping away for hours at a time, was entirely and tragically accurate.

Most of all, thanks are due to the impossibly patient Dee Street, who was Dee Hurley at the beginning of the process and still inexplicably went through with a wedding that occurred weeks after I agreed to write this, well before she knew what she was getting into.

As best as I can tell shes the very finest person on the planet and Im impossibly fortunate to have her in my life-corner.

In which the auguries show stormy weather ahead for the people of Australia

In order to explain how the Abbott government stumbled into power, its important to give some context and outline how the nation had been faring during the previous few years. This is what the great playwrights call foreshadowing.

In November 2007, the Labor government under Kevin Rudd had wiped out the Coalition government of John Howard. It seemed like the sort of thumping triumph that would not only usher in a new epoch for the party, following the end of Howards eleven-year reign, but potentially consign the Liberal and National parties to history.

Hilarious though it may now seem, following the 2007 landslide there were high-minded editorials speculating on whether this marked the end of right-wing politics per se and heralded a new, less economically driven era in Australia, in which the debate would be less between the interests of employers versus the employed and more between maintaining jobs versus preserving the environment.

Oddly enough, this Labor-versus-Greens future has yet to pass, but many of the seeds of Labors later problems were sown in its electoral triumph. First up, the party faced the problem of every party that wins a comprehensive victory after a long time in the wilderness: inevitably, the government benches were filled with a large, unwieldy collection of MPs. This wasnt unique; with any party in any epoch, this endless shifting of such an unbalanced load is part of what keeps the truck of Australian governance swerving wildly from left to right as it barrels down Democracy Highway.

Hence the Rudd benches were filled with new, inexperienced MPs whod been plonked in the gig because of anger with the previous government rather than any particular local enthusiasm for the individual, mixed in with veteran incumbents terrified that this was their last chance to prove themselves and make their mark.

So far, so typical. What was unusual this time around was the new prime minister.

Kevin Rudd had already proved himself an ideas man during his relatively brief tenure in the federal party. Hed only entered the House of Representatives in 1998, after a stint in Queensland state politics serving as premier Wayne Gosss chief of staff. In 2001, he became Shadow Minister for Foreign Affairs and quickly gained a high profile, particularly after Australia entered the war in Iraq in 2003.

Rudd entered the shadow ministry when Simon Crean was leader; he continued under Mark Latham, despite having supported Lathams rival Kim Beazley when Crean resigned. When Latham led the party to defeat in 2004, Beazley was returned as leader unopposed, even though Rudd was now being touted as a possible contender. However, it seemed that Rudd was set to play a strong supporting role as a frontbencher in a future Beazley government. After all, given Labors recent history, maybe it was time to get behind a consensus builder of the middle ground like Beazley rather than a Latham-style visionary hothead like Rudd, who already had a private reputation within the party for tantrum-throwing, not to mention a revolving door of staff.

However, by mid-2006 the polls were consistently showing higher public approval for the beaming, multilingual Queenslander than the stout, cautious Western Australian. As the year drew to a close, Beazley sought to end leadership speculation before preparations for the following years election began in earnest. By calling for a leadership vote, Beazley placed his neck in a noose, and on 4 December, Labor had a new leader.

Rudd was beloved by a good slab of the public for his future-focused approach compared with the increasingly tired-looking Howard, who was widely (and, as it turned out, correctly) assumed to be planning to hand over the leadership to the even-less-beloved treasurer, Peter Costello, inside of twelve months in the event that he won the election. Even so, there were rumblings behind closed doors about Rudds temper, his inability to delegate to others, and his refusal to brook dissent. However, he also looked like the man best suited to trounce the listing Coalition government. And on 24 November 2007, he did exactly that.

And that really should have been the end of the story of Rudd too: popular reformer makes popular reforms. And its worth remembering that he actually did achieve much: there was the apology to the Stolen Generations, there was the ratification of the Kyoto Protocol after endless hedging by the Howard government, and there was even bipartisan support for an emissions trading scheme with the Coalition led by Malcolm Turnbull.

And there was something else that should have cemented Labors hold on government in Australia for a generation: less than a year after Rudd took power, the worlds economic system abruptly collapsed.