KOH-I-NOOR

BY THE SAME AUTHORS

by William Dalrymple

In Xanadu

City of Djinns

From the Holy Mountain

The Age of Kali

White Mughals

The Last Mughal

Nine Lives

Return of a King

by Anita Anand

Sophia

KOH-I-NOOR

The History of the Worlds Most Infamous Diamond

William Dalrymple

Anita Anand

Contents

On 29 March 1849, the ten-year-old maharaja of Punjab, Duleep Singh, was ushered into the Shish Mahal, the magnificent mirrored throne room at the centre of the great fort of Lahore.

The boys father, Maharaja Ranjit Singh, was long dead, and his mother, Rani Jindan, had been forcibly removed some time earlier and incarcerated in a palace outside the city. Now Duleep Singh found himself surrounded by a group of grave-looking men wearing red coats and plumed hats, who talked among themselves in an unfamiliar language. In the terrors of the minutes that followed what he later remembered as the crimson day the frightened but dignified child finally yielded to months of British pressure. In a public ceremony in front of what was left of the nobility of his court, he signed a formal Act of Submission, so accepting the punitive Terms offered to him by the victorious Company. Within minutes, the flag of the Sikh kingdom was lowered and the British colours run up above the gatehouse of the fort.

The document signed by the ten-year-old maharaja handed over to a private corporation, the East India Company, great swathes of the richest land in India land which until that moment had formed the independent Sikh kingdom of Punjab. At the same time Duleep Singh was induced to hand over to Queen Victoria the single most valuable object not just in Punjab but arguably in the entire subcontinent: the celebrated Koh-i-Noor, or Mountain of Light.

Article III of the document read simply: The gem called the Koh-i-Noor, which was taken from

The East India Company, the worlds first really global multinational, had grown over the course of little more than a century from an operation employing only thirty-five permanent staff, headquartered in one small office in the City of London, into the most powerful and heavily militarised corporation in history: its army by 1800 was twice the size of that of Britain. It had had its eyes on both Punjab and the diamond for many years.

Its chance finally came in 1839, on the death of

At the end of the same year, on a cold, bleak day in December, Dalhousie arrived in person in

Less than a week later, Dalhousie wrote to a junior assistant magistrate in Delhi, askingDalhousie liked the boy. He therefore chose Theo to carry out an important and somewhat delicate task.

The Koh-i-Noor may have been made of the earths hardest substance, but it had already attracted an airily insubstantial fog of mythology around it, and Dalhousie wanted to establish the solid truth about its

Theo went about his task with characteristically slapdash enthusiasm. But as the gem had been stolen away from Delhi during a Persian invasion a full 110 years earlier, his job was not easy. Even he had to admit that he had gathered little more than bazaar tittle-tattle: I cannot but regret that the results are so very meagre and imperfect, he wrote in the preamble to his report. He nevertheless laid out in full his findings, making up in colour for what he lacked in accurate, substantiated research.

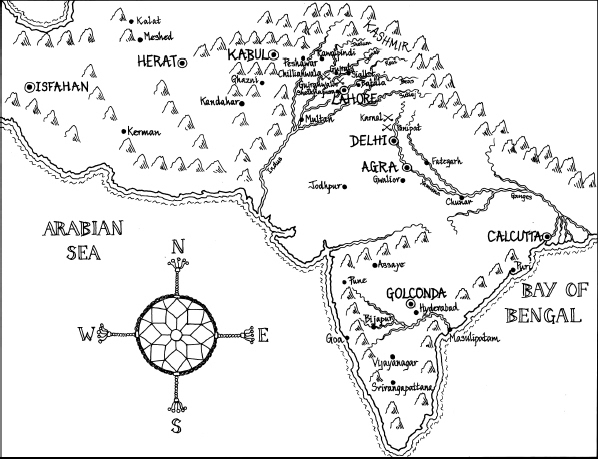

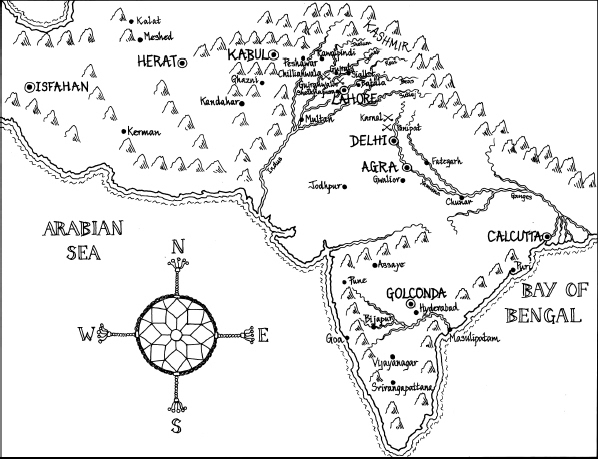

First, wrote Theo, according to the tradition of the eldest jewellers in the City of Delhee, as handed down from family to family, this diamond was extracted from the mine Koh-i-Noor, four days journey from Masulipatnam to the north west, on the banks of the

Theos report, which still exists in the vaults of the Indian National Archives, continued in this vein, sketching out for the first time what would become the accepted history of the Koh-i-Noor: a centuries-long chain of bloody conquests, and acts of pillage, looting and seizure. Theos version of events has since been repeated in article after article, book after book, and still sits unchallenged on Wikipedia today.

Discovered in the deepest mists of antiquity, the great diamond was said to have been looted, probably from the eye of an idol in a temple in southern India, by marauding Turks. Soon, Theos report continues, the jewel fell into the hands of the Emperors of the Ghoree dynasty, and from then successively of the [fourteenth-century] Tughluq, Syed and the Lodhi dynasties, and eventually descended to the family of Timur [the Mughals] and remained in their possession until the reign of Mohammud Shah, who wore it in his Turban. Then, when the Mughal Empire crumbled under the invasion of the Persian warlord Nader Shah, the Emperor and he exchanged Turbans, and thus it became the property of the latter. Theo went on to claim that it was named Koh-i-Noor by Nader Shah, and that it passed at his death to his chief Afghan bodyguard, Ahmad Khan Abdali. From there it spent nearly a hundred years in Afghan hands, before Ranjit Singh extracted it from a fleeing Afghan shah in 1813.

Shortly after Theo had delivered his report, the Koh-i-Noor was dispatched to England where Queen Victoria promptly lent it to the Great Exhibition of 1851. Long queues snaked through the Crystal Palace to see this celebrated imperial trophy locked away in its specially commissioned high-security glass safe, itself contained within a metal cage. Trumpeted by the British press and besieged by the British public, the Koh-i-Noor quickly became not only the most famous diamond in the world, but also the single most famous object of loot from India. It was a symbol of Victorian Britains imperial domination of the world and its ability, for better or worse, to take from around the globe the most desirable objects and to display them in triumph, much as the Romans once had done with curiosities from their conquests 2,000 years earlier.

As the fame of the diamond grew, and as Theos enjoyably lively

In reality, it was only really in the early nineteenth century, when the Koh-i-Noor reached Punjab and the hands of Ranjit Singh, that the diamond began to achieve its pre-eminent fame and celebrity so much so that by the end of Ranjits reign pious Hindus were beginning to wonder if the Koh-i-Noor was actually the legendary Syamantaka gem mentioned in the Bhagavad Puranas tales of Krishna.

This growing fame was partly the result of Ranjit Singhs preference for diamonds over rubies a taste Sikhs tended to share with most Hindus, but not with the Mughals or Persians, who preferred large, uncut, brightly coloured stones. Indeed in the Mughal treasury, the Koh-i-Noor seems to have been only one among a number of extraordinary highlights in the greatest gem collection ever assembled, the most prized items of which were not diamonds at all, but the Mughals beloved red spinels from Badakhshan and, later, rubies from Burma.

The growing status of the Koh-i-Noor was also partly a consequence of the rapidly growing price of diamonds worldwide in the early and mid-nineteenth century. This followed the invention of the symmetrical and multi-faceted brilliant cut, which fully released the fire inherent within every diamond, and which led in turn to the emerging fashion in middle-class Europe and America for diamond engagement rings a taste which was eventually refracted back to India.

The final act in the Koh-i-Noors rise to worldwide fame took place in the aftermath of the Great Exhibition and the press coverage it had engendered. Before long, huge, often cursed Indian diamonds began to make regular appearances in popular Victorian novels such as Wilkie Collinss

Next page