For my sisters,

Maureen and Linda

West wind, wanton wind, wilful wind, womanish wind, false wind from over the water.

George Bernard Shaw, St Joan

The Zephyr programme is monitoring the progress of Britains only spy satellite. When Zephyr goes briefly off the air, technician Martin Hepton finds himself in danger and the mistrusted Mike Dreyfuss, a British astronaut who is the sole survivor of a shuttle crash in America, has the only key to the riddle that must be solved if both men are to stay alive.

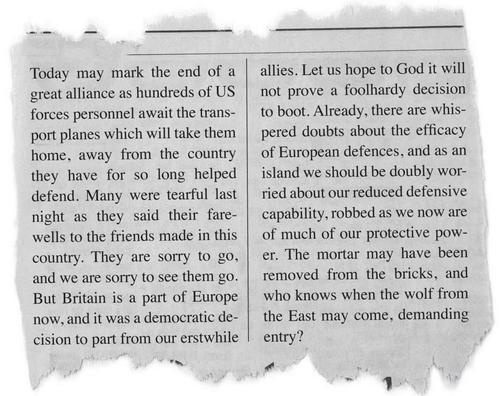

Editorial in

London Herald, 15 July 1990

He watched the planet earth on his monitor. It was quite a sight. Around him, others were doing the same thing, though not perhaps with an equal sense of astonishment. Some had grown blas over the years: when youd seen one earth, youd seen them all. But not Martin Hepton. He still felt awe, reverence, emotion, whatever. If he had called it a spiritual feeling, the others might have laughed, so he kept his thoughts to himself. And watched.

They all watched, recording their separate data on the computer, keeping an eye on earth from the heavens while their feet never left the ground. Hepton felt giddy sometimes, thinking to himself: this is the only earth there is, and were all stuck with it, every last one of us. At such moments, the thought of war seemed impossible.

The ground station at Binbrook was small by most standards, but quite large enough for its purpose, and it was sited in the midst of the greenest countryside Hepton had ever seen. He had been born here in Lincolnshire, but had grown up in 1960s London; swinging London. It had swung right past him. With his head stuck in this or that textbook he had never quite noticed the bright clothes, the casual attitudes, the whole hippy shake. Too often, when his head wasnt in a book, it had been raised to the sky, naming a litany of stars and constellations. And it had led to this, as though by some predetermined scheme. He had reached for the skies and had touched them. Thanks to Zephyr.

Zephyr was the reason behind all this activity, all these monitors and busy voices. Zephyr was a British satellite. The British satellite. It wasnt the only one they had, but it was the best. The best by a long shot. It could be used for just about anything: weather-watching, communications, surveillance. It could drop from its orbit to within a hundred kilometres of earth, take a pristine picture, then boost back into the higher orbit again before relaying the information back to the ground station. It was a clever little sod all right, and here were its nursemaids, keeping a close eye on it while it kept a close eye on the British Isles. Nobody seemed quite sure why Britain was Zephyrs present target. Word had gone around that the brass meaning the military and the MoD wanted to survey this sceptred land, which was fine by Hepton. He would never tire of staring at the various screens, seeing what his satellite saw, making sure that everything was recorded, filed, double-checked. And then viewed by the generals and the men in the pinstripe suits.

He had his own ideas about the present surveillance. The United States was pulling its troops out of Europe. It all looked amicable and agreed, but rumours had started in the press, rumours to the effect that there had been a good amount of shove on the part of the mainland European countries, and that the American generals werent entirely happy about leaving. The rumours had led to some demonstrations by right-wing parties, asking that the USA stay! USA stay!, and an organisation of that name had quickly been formed. More demos were now taking place, and vigils outside the embassies of Britains partners in Europe. Not exactly powder-keg stuff, but Hepton could imagine that the government wanted to keep things nailed down. And who better than Zephyr to follow a convoy of protesters or keep tabs on rallies in different parts of the country?

All at the touch of a button.

Coffee, Martin? A cup appeared beside his console. Hepton slipped his headphones down around his neck.

Thanks, Nick.

Nick Christopher nodded towards the screen. Anything good on the telly? he asked.

Just a lot of old repeats, answered Hepton.

Isnt that just typical of summer? Honestly, though, Ill go mad if we dont get some new schedules soon.

Maybe were due for a little excitement.

What do you mean? asked Christopher.

Well, said Hepton, cradling the plastic beaker, Ive heard that the brass are around today. Maybe Fagin will put on a simulation for them, show them were on our toes.

Anything for a shot of adrenaline.

Hepton stared at Nick Christopher. Rumour had it that at one time hed shot more than just adrenaline. But that was the base for you: when nothing was happening, the rumours seemed to start. Christopher was reaching into his back pocket. He brought out a folded, dog-eared newspaper, its crossword nearly completed. Hepton was already shaking his head.

You know Im never any good at those, he said. Nick Christopher was a crossword addict. Hed buy anything from a kiddies puzzle book to The Times to feed his habit, and over by his desk he had weighty tomes dedicated to his pursuit: dictionaries, collections of synonyms and antonyms and anagrams. He often asked Heptons help, if only to show how close he had come to solving the days most difficult puzzle. Now he shrugged his shoulders.

Well, see you at break time, he said, heading back towards his own console.

Biccies are on me, Hepton said.

There was a sudden wrenching of the air as an alarm began to sound, and Christopher turned back to smile at him, as if to congratulate him on his hunch. Hepton put down his coffee untouched and checked the screen. It was filled with flickering white dots, static. The other screens nearby were showing the same electronic snow.

Lost visual contact, someone felt it necessary to say.

Weve lost all contact, called out another voice.

It looked as though Fagin had set them up after all. There was immediate activity, chairs swivelling as consoles were compared, buttons clacked and calls made over the intercom system. Despite themselves, they all relished the occasional emergency, contrived or not. It was a chance to show how prepared they were, how efficient, how quickly they could react and repair.

Switching to backup system.

Coding in channel two.

Im getting a very sluggish response.

So stop talking to snails.

An arm snaked past Heptons shoulder and punched numbers out on his keyboard, trying to elicit a response from their own. Nothing. It was as if some television station had packed up for the night. All contact had been lost. How the hell had Fagin rigged this?

Hepton lifted his coffee to his lips, gulped at it, then squirmed. Nick Christopher must have dropped a bag of sugar into it.

Sweet Jesus, he muttered, the fingers of one hand still busy on his keyboard.

Coded through.

No response here.

Im getting nothing at all.

A voice came over the speaker system, replacing the electronic alarm.

This is not a test. Repeat, this is not a test.

They paused to look at each other, reading a fresh panic in eyes reflecting their own. Not a test! It had to be a test. Otherwise theyd just lost a thousand million pounds worth of tin and plastic. Lost it for how long? Hepton checked his watch. The system had been inoperative for over two minutes. That meant it really was serious. Another minute or so could spell disaster.

Editorial in London Herald, 15 July 1990

Editorial in London Herald, 15 July 1990