Candace Robb

The Owen Archer Series:

Book Ten

A VIGIL OF SPIES

2008

To all those with the courage to open their hearts.

I would like to thank Anthony Goodman for his insights into Joan of Kent, shared over a long, happily drawn-out lunch on a warm afternoon in the courtyard of St Williams College, York; Carolyn Collette for generously sharing her research on Joan; Laura Hodges for her expertise in the clothing of the period; Lorraine Stock for tracking down an obscure but important article about Alexander Neville; Laurel Broughton for finding just the right epigraph from Geoffreys pen; and Barbara Johnson for asking the right question about what Thoresby means to me. My friends on Chaucernet have been sources of ideas and information for the character of Geoffrey Chaucer and details of the age. I also wish to thank Georgina Hawtrey-Woore and Patrick Walsh for early input on the manuscript, and Joyce Gibb for a thorough reading of the complete draft. I am, as ever, grateful to my husband Charlie for his support behind the scenes.

coney: rabbit

cotehardie: a tight tunic for men; a long, tight fitting gown for women

girth: a cinch on a western saddle

jupon: a tight tunic, usually without sleeves

Order of the Garter: a society of lay knights founded by Edward III in 13489, dedicated to St George, its device a blue garter; the first group included twenty-six knights

scrip: a small bag, wallet, or satchel

solar: private room or rooms on an upper level of a house

staithe: a landing-stage or wharf

surcoat: an outer coat, or garment, usually of rich material; if wearing armour, this would be worn over the armour, whereas the jupon would be worn under the armour

certainly a man hath moost honour

To dyen in his excellence and flour,

Whan he is siker of his goode name;

Thanne hath he doon his freend, ne hym, no shame.

Geoffrey Chaucer, The Knights Tale

Oh what a tangled web we weave,

When first we practise to deceive!

Sir Walter Scott

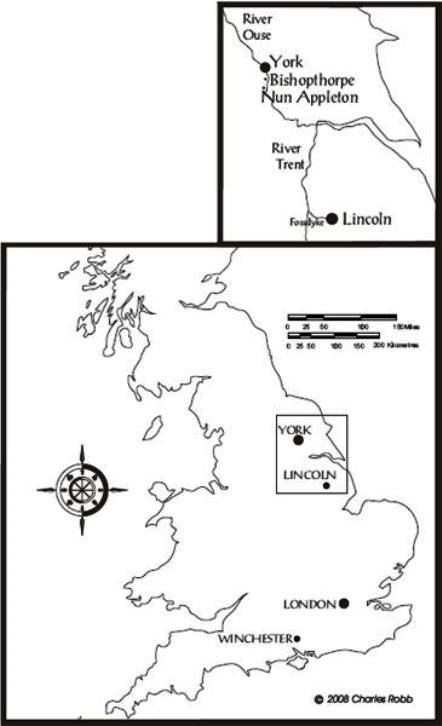

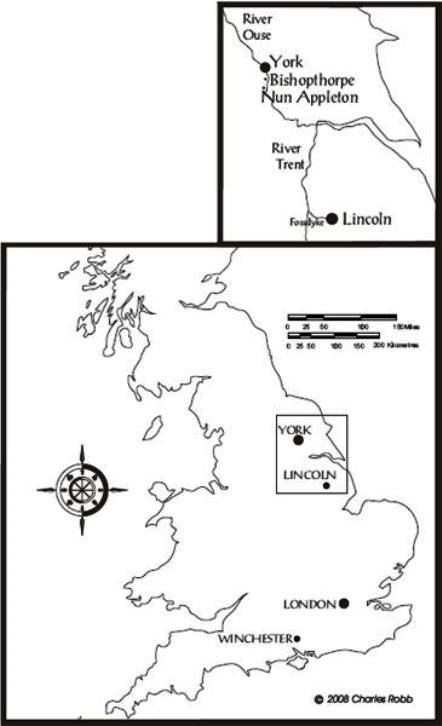

Bishopthorpe Palace, late September 1373

Archbishop Thoresby held up his hand to silence Brother Michaelos arguments. Gods will does not align with ours, Michaelo. We tried and failed. The chapter will not choose my nephew Richard to succeed me. It is finished.

Though His Graces voice was weak, his personal secretary heard in it the clear resolve. He reminded himself of the fourth step of humility in St Benedicts rule To go even further than [simple obedience] by readily accepting in patient and silent endurance, without thought of giving up or avoiding the issue, any hard and demanding things that may come our way in the course of that obedience We are encouraged to such patience by the words of scripture: Whoever perseveres to the very end will be saved. Bowing, Michaelo began to back away from the great bed.

I had not realised how much you had set your heart on Richard succeeding me, said Thoresby. Why, Michaelo?

In his minds eye, Michaelo was back at the wretched day ten years earlier when he lay at the entrance to the abbey oratory, his forehead pressed to the cold, indifferently cleaned tiles, while his brethren shuffled past him. A few stumbled on his robes, one grazed his foot, another kicked his right hand. Then came a long silence in which his attempts to pray that this prostration might signal his repentance and his humility were overridden by his self-loathing. He could not believe that God wished to hear him. Ten years in Thoresbys service had restored his belief, his ability to pray. Hed believed that in the service of Richard Ravenser he would yet be safe from himself.

I cannot return to St Marys Abbey, Your Grace.

That choice passed with Abbot Campions death. We spoke of a modest priory in Normandy where you might retreat into silent prayer. My nephew will see to that.

A small priory in his native Normandy, near his kin, in perpetual retreat. Michaelo knew it to be a wise choice, and yet he doubted his ability to surrender to it. He was but thirty-five, too young to die to the world. He doubted that years of silent prayer and mortification of the flesh could protect him from the inevitable encounter with a young monk who stirred his desire. This was the devil undermining his courage. The devil who knew him.

God go with you, Your Grace, Michaelo murmured, then turned and withdrew from the sickroom. Alone in the corridor, he slumped against the wall and prayed for the strength to remain by His Graces side to the end, for the fortitude to resist the terror that bade him flee before despair overcame him. As the archbishops personal secretary, Michaelo had found his way to grace as if residing in the presence of a man of grace had transformed him. But he feared for his strength once Thoresby died, and his death was imminent. The archbishop would not live to see another Christmas, so predicted the healer Magda Digby. Brother Michaelo felt the devil hovering over his left shoulder, whispering darksome thoughts in quiet moments.

His only hope had been in His Graces winning the dean and chapters support for his nephew, Sir Richard Ravenser, to succeed him as Archbishop of York. Ravenser had asked Michaelo to serve him as his personal secretary if he won the election. But, except for a few of the Thoresby/Ravenser kin in the chapter and their old friend Nicholas Louth, the canons supported Alexander Neville, for King Edward apparently approved of him, or so claimed the Neville family in their aggressive campaign.

Michaelo rubbed his left shoulder. Already it ached with hellish cold.

Monday

Captain Owen Archer stood in a shaft of sunlight with his lieutenants, Alfred and Gilbert, his scarred but handsome face grim as he spoke to them. As Brother Michaelo rushed about, overseeing the preparations for the large and grand company of guests expected to arrive by mid-afternoon, he caught snippets of the captains commands. The fair Gilbert was to ride out with a group of guards to surround the company as it approached, and the lanky, balding Alfred was in charge of the guard protecting the perimeter of the manor of Bishopthorpe. Noticing a deep shadow beneath Archers good eye and how he wearily rubbed the scar beneath his leather eye patch, Michaelo remembered their conversation the previous evening.

Archer had reluctantly admitted that he would miss Archbishop Thoresby, and that he resented the danger Princess Joans visit presented. With King Edward and his heir and namesake both ailing and the Archbishop of York on his deathbed, the Scots might anticipate sufficient disarray in the northern defences that they could easily seize Prince Edwards wife as she travelled so far north. The French had no love for Prince Edward, who had proven his military prowess on their soil all too frequently, and the new King Robert II of Scotland, having renewed the Franco-Scottish alliance, might enjoy handing Edwards wife to the French king to prove his worth.

His Grace should have peace in his final days and not be worrying about the possibility of such a disaster, Archer had said, smacking the table with his hand. I would have it so.

His voice broke with the last words that was when Michaelo plumbed the depths of the captains affection for the archbishop. It surprised him. Archer had spent a decade resenting His Grace. Michaelo wondered at this change.