Candace Robb

The Owen Archer Series:

Book One

THE APOTHECARY ROSE

1993

To Gen, who first got me to England;

to Jacqui, the apothecary;

and to Charlie, who always makes it so.

The lyf so short, the craft so long to lerne,

Thassay so hard, so sharp the conquerynge,

The dredful joye, alwey that slit so yerne

Geoffrey Chaucer, The Parlement of Foules

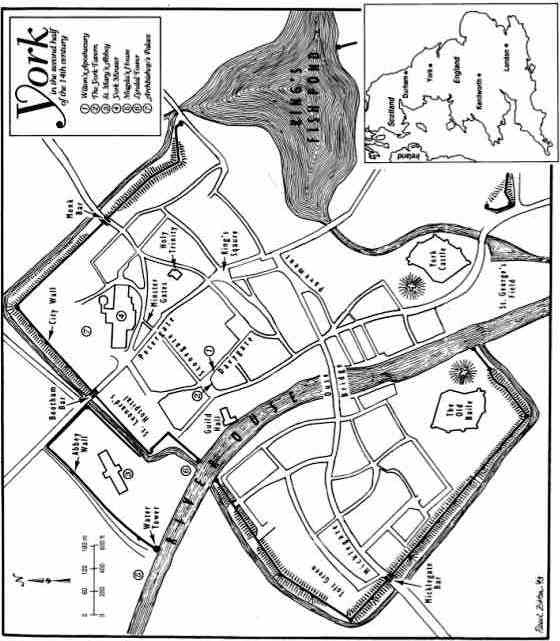

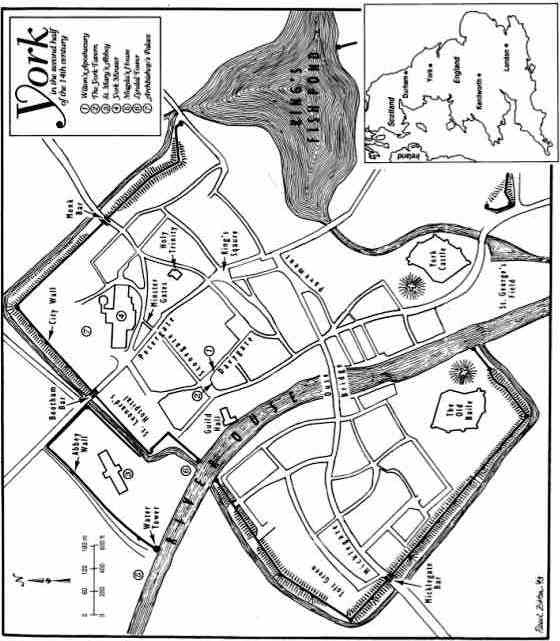

I thank Lisa Healy for her long-term faith in me and a crucial editing; Paul Zibton for the map, sanity lattes, and a critical reading; Christie Andersen for allowing me the time to write this book; Liz Armstrong for making all my medieval literature courses a joy; Paula Moreschi for keeping mind and body sound through it all; Evan Marshall for turning bad news into good news; Michael Denneny and Keith Kahla for making me feel welcome at St. Martins; the staffs of the University of Yorks Borthwick Institute and the Morrell Library; the York Archaeological Trust; Dr. Tom Lockwood, chairman of the English Department at the University of Washington; and, most of all, Charles Robb for providing time, computer resources, food, drink, criticism, enthusiasm, travel arrangements, and organization, for outfitting me for exploring ruins in Yorkshire in a very cold December, and for insisting that a house is not a home without two spoiled cats.

archdeacon: each diocese was divided into two or more archdeaconries; the archdeacons were appointed by the archbishop or bishop and carried out most of his duties

jongleur: a minstrel who sang, juggled, tumbled; French term, but widely used in an England where Norman French was just fading from prevalence

leman: mistress

minster: a large church or cathedral; the cathedral of St. Peter in York is referred to as York Minster

summoner: an assistant to an archdeacon who cited people to the archbishops or bishops consistory court, which was held once a month. The court was staffed by the bishops officials and lawyers and had jurisdiction over the diocesan clergy and the morals, wills, and marriages of the laity. The salary of a summoner was commission on fines levied by consistory courts petty graft formed a large part of his income. More commonly called an apparitor, but I use the term Chaucer used to call to mind the Canterbury pilgrim he so vividly described.

Brother Wulfstan checked the color of his patients eyes, tasted his sweat. The physick had only weakened the man. The Infirmarian feared he might lose this pilgrim. Trembling with disappointment, Wulfstan sat himself down at his worktable to think through the problem.

The pilgrim had arrived pale and hollow-cheeked at St. Marys Abbey. Released from the Black Princes service because of wounds and a bout with camp fever, the man had resolved to come on pilgrimage to York, his wounds making him more aware of his mortality than any sermon ever had. Hed endured a rough channel crossing and a long ride north that had reopened his wounds. Wulfstan had stopped the bleeding with periwinkle, but the recurrence of the fever caught him ill prepared. The Infirmarian had little experience with the ailments of soldiers, having lived in the cloistered peace of St. Marys since childhood. He rarely ventured farther from the abbey than York Minster or Nicholas Wiltons apothecary, both within a short walk.

For two days and a night Wulfstan mixed physicks, applied plasters, and prayed. At last, exhausted and sick at heart, he thought of Nicholas Wilton. It was a sign of his hysteria that Wulfstan had not thought of the apothecary before Nicholas had worked a wondrous cure on a guest of the Archbishop whod been near death with camp fever. He would know what to do. Wulfstan breathed three Aves in thanksgiving as his spirits soared. God had shown the way.

The Infirmarian instructed his novice, Henry, to keep the pilgrims lips moist and to prepare a mint tisane for him to sip if he roused. Then Wulfstan hurried through the cloister to ask the Abbots permission to go into the city. He brushed at the powder and bits of dried herbs on his habit. Abbot Campian was a fastidious man. He believed that a tidy appearance bespoke a tidy mind. Wulfstan knew the Abbot could hardly disagree with his mission, but he found comfort in rules, as the Abbot did in tidiness. Wulfstan believed that if he obeyed and did his best, he could not fail to win a place, though humble, in the heavenly chorus. To be at peace in the arms of the Lord for all eternity. He could imagine no better fate. And rules showed him the way to that eternal contentment.

With his Abbots permission, Wulfstan stepped out into the December afternoon. Bah. It had begun to snow. All through November and into December hed awaited the first snow, and it came now, when he had an urgent errand. If hed been a superstitious peasant, he would have suspected the fates were against him today. But he fortified himself with the conviction that as God had seen him through all the small troubles of his life, surely He could not mean to desert Wulfstan at this late date.

The Infirmarian pulled up his cowl and headed into the wind as fast as he could, blinking and puffing, out the Abbey gates and onto the cobbled street, into the bustle of York. The cacophony of the city startled Wulfstan out of his single-minded hurry. He became aware of a stitch in his side. His heart hammered. Such signs of frailty frightened him. He was behaving like a fool. He was too old to move so quickly, especially on cobbles made slippery with the first snow. Holding his side, he paused at the crossroads for a passing cart. The snow came down thick now, great, fluffy flakes that stung as they melted on his flushed cheeks. Overheat and then chill. Youre an idiot, Wulfstan. He turned down Davygate, trying to moderate his speed. But Wiltons shop was just past the next crossing. He was so close to his goal. He picked up his pace again, propelled forward by fear of losing his patient.

Wulfstan had grown fond of the pilgrim in a short time. The man was a soft-spoken, gentle knight who identified himself only as a pilgrim wishing to pray, meditate, make his peace with God. He carried with him an old sorrow, the love of a woman who belonged to someone else. He spoke of her as the gentlest, most beautiful woman, whose purgatory on earth was to be tied to an old man who gave her no joy. What would she think of me now, eh, my friend? His eyes would mist over. But she is gone. The pilgrim came daily to the infirmary to have Wulfstan change his bandages. During these visits he had discovered the herb garden, how its beauty comforted the heart, even in winter. She found solace in a garden much like this. Many a day the pilgrim lingered there while Wulfstan puttered in the beds. He said little, observing the monastic rule of speaking only when necessary. He was ever ready to assist with carrying or fetching, sensitive to Wulfstans old bones. Wulfstan enjoyed the mans quiet companionship and appreciated his help, though he knew accepting it was sinful indulgence.

So he had taken it hard when the pilgrim collapsed in chapel. The man had been keeping a vigil that night in memory of his love. Brother Sebastian found him in a swoon on the cold stone floor at Lauds. Thanks be to God for the night office, or the pilgrim might have lain there till dawn and caught a mortal chill.

Even so, he was very ill. Wulfstan hurried. By the time he pushed open Wiltons shop door, the old monk was panting and bent double, clutching his side. The dimness of the shop and his own weakness blinded him momentarily; he could not see if anyone was in the shop. Gods peace be with you, he gasped. No answer. Nicholas? Lucie?