Candace Robb

The Owen Archer Series:

Book Eight

THE CROSS-LEGGED KNIGHT

2002

In memory of two dear men lost to me this year, Dad (Benjamin Chestochowski, 9 March 1920 12 August 2001) and Uncle John (John Wojak, 7 August 1925 3 January 2001).

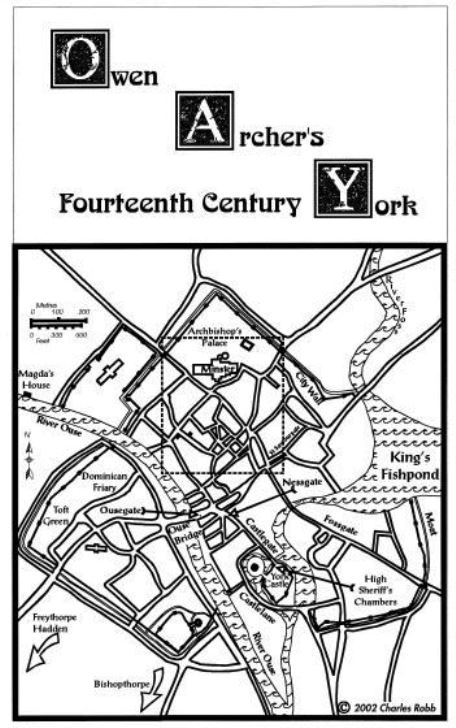

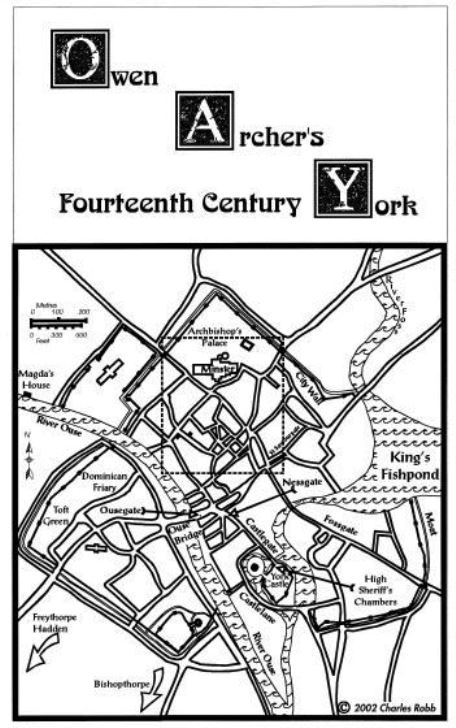

I am indebted to Ed Robb for bringing to bear his 35 years of expertise in research at Shriners Childrens Hospital, a pediatric hospital for burns, in answering my many questions about burns and the healing methods available to Magda Digby; to Charlie Robb for all his support, particularly in mapping the city of York, describing the archbishops palace, and brainstorming on the plot; to Lynne Drew, Sara Ann Freed, Evan Marshall, and Patrick Walsh for patience and sympathetic support during a difficult year; to Joyce Gibb, Laura Hodges, and my generous colleagues on Chaucernet, Medfem, and Mediev-1 for advice and comraderie throughout this project; and to Jacqui, Mark, Nathaniel and Emily Weberding for their boundless love and compassion.

October 1371

William of Wykeham, Bishop of Winchester and late Lord Chancellor of England, sat in the mottled shade of Archbishop Thoresbys rose arbour wiping his irritated eyes and cursing all that had brought him riding to York four days ago. The horses hooves had stirred up summers dust and the mould from the autumn leaves. He and his entourage had ridden with cloths covering their faces from their chins to the bridges of their noses. Wykeham might have pampered himself within the curtains of a litter, but he had not wished anyone to misconstrue such a nicety, spread word that he had hidden from the curious along the way, or, worse yet, that he was ill, weak. So he had ridden north on the Kings Highway with his men, regretting that the rains of autumn had held off for his journey to York.

They had stopped frequently and broken their journey early in the evenings. Wykeham would have preferred a brisker pace, but now that the chain of lord chancellor no longer weighed down his neck, he did not push his men, for they, too, as his household, had lost stature this past year. It was not as fine to be the household officers of the Bishop of Winchester as it had been to be the officers of the lord chancellor of the realm. Wykeham wanted them content. His enemies would be only too happy to make alliances with his staff.

He had used the time to pick at his wounded dignity. God knew he could have found better occupation for his hours in the saddle, but he was weak, too proud, he knew that of himself.

Their small wagon had creaked and groaned over the ruts in the road, its cargo the heart of a York knight who had gone in his dotage to France as a spy and had been caught and imprisoned, dying there while Wykeham was negotiating his ransom. The Pagnell family were making much of what they considered Wykehams failure, though he was of the opinion that Sir Ranulf Pagnell had simply been a foolish old man. However, as the family was influential in Lancastrian circles Wykeham had tried to appease them by escorting Sir Ranulfs remains to York, the heart that he had coaxed from the French king with his own money. The Pagnells did not think even this sufficient retribution. For all his efforts, Wykeham was not to preside at the knights requiem. Indeed, he had not even been invited to attend.

As Wykeham sat in the archbishops garden, miserable in his self-pity, a shadow fell across him and the scent of lavender drew him from his thoughts. He squinted up, his eyes watering in the light. Brother Michaelo, the archbishops elegant secretary, stood before him.

Wykeham assumed the monk had come to deliver a message. What news from Lady Pagnell?

Michaelo bowed his head slightly. The lady sends her apologies, but she cannot meet with you until her departed husbands months mind.

Wykeham bristled. How can there be a one-month mass for Sir Ranulf when we know not the date of his death?

She means a month from his burial, My Lord Bishop, a month from tomorrow.

Lady Pagnell and her son and heir, Stephen, were being guided in this shunning of him by their Lancastrian friends, Wykeham was sure of it. But to press her would merely inspire accusations of cruelty to the widow in her mourning. He could ill afford to make himself more unpopular in the city than he already was.

Brother Michaelo held up to him a glass vial. If I might suggest, My Lord Bishop, a soothing wash for your eyes? This is from Captain Archers wife. She is as skilled as any apothecary you might have in Winchester.

Wykeham grunted. I am in your debt. Take it to my servant. I shall try it later.

I could assist you in applying a few drops now, My Lord Bishop.

And make him look a fool, with the liquid staining his face, his silk clothing. To my servant, Brother Michaelo.

The monk bowed and withdrew.

Wykeham fell back into his dudgeon. Ungrateful family, the Pagnells. But they would see, he would not idle away the rest of his life waiting on the likes of Lady Pagnell. The king would have him back.

He shaded his eyes and gazed upon the great minster across the garden. A building project would be to his liking right now. As he rode north he had thought about the ruined church of All Saints in Laughton-en-le-Morthen. Though it was no longer his prebend, he meant to rebuild it. He rose with a thought to observe the work on the minster Lady Chapel, a better occupation than wallowing in self-pity.

Wishing to be truly free for a little while, Wykeham watched the household guards for a chance to depart unescorted. He felt like a truant schoolboy as he hurried through the gate and towards the minster. Winded and silently laughing at his foolishness, he almost forgot the grit in his eyes, but soon the burning began anew. He caught his breath and dabbed at his eyes, determined to enjoy this moment alone.

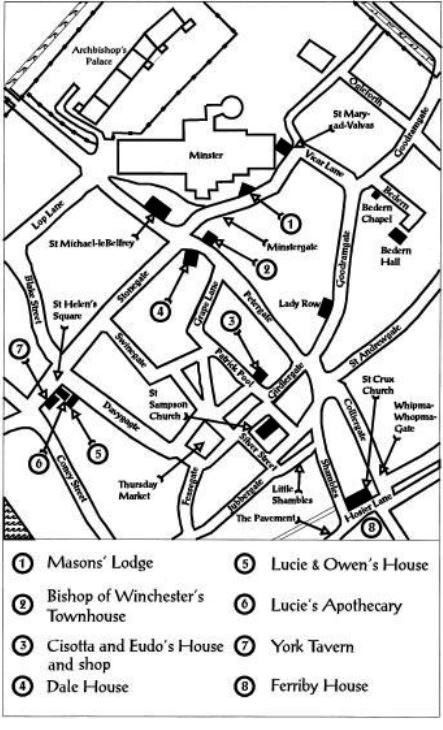

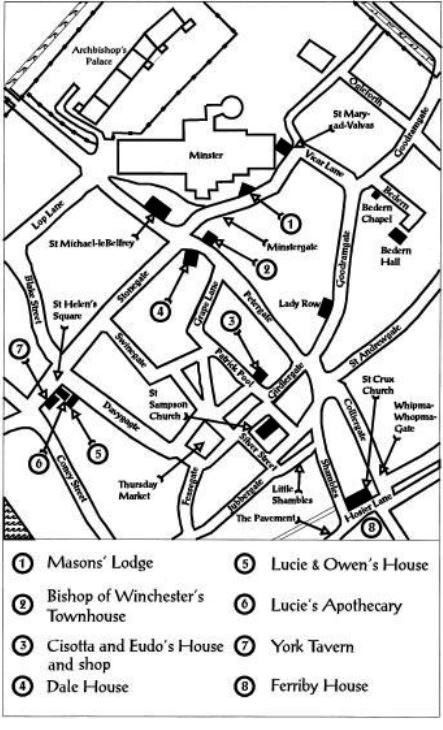

To his left the south side of the minster nave soared above him, to his right St Michael-le-Belfrey cast a late-afternoon shadow. As he rounded the south transept his view of the construction was blocked by a huge mound of stones and tiles butted up against what had been the far south-east corner of the minster before work on the Lady Chapel began. The church of St Mary ad Valvas had been dismantled to create room for the construction, and the stones and tiles were being reused, though much of them merely for rubble within the walls. Skirting the mound Wykeham saw two men chiselling stones in the masons lodge. As he considered whether to interrupt their work a shout startled him.

My Lord, drop down and cover your head!

He did as he was told, and just in time. A heavy clay tile thudded on to the path a hands breadth short of him, cracking on impact. He curled into himself so tightly he had difficulty breathing. But he would not lift his head; he dared not. He did not mean to play Saint Thomas Becket to the Duke of Lancasters Henry II. He would not be so easily murdered.

Owen Archer feared the worst as he crouched beside the unmoving figure. My Lord, are you injured?

As he was searching for a pulse the bishop stirred beneath him. Slowly Wykeham raised his head. Archer, I do not think I am injured. He was very pale and his breathing shallow.

By now masons and soldiers crowded round the kneeling pair, and Alain, one of the bishops clerks, assisted Owen in helping Wykeham to stand.