This book is dedicated to the memory of

Trooper Troy Duncan and the Alaska police

officers who put their lives on the line that the

rest of us may live in peace.

FOREWORD

Is it just imagination or does murder in Alaska have a special edge, a rawness that suggests the violation of a dream?

Homicide happens everywhere, in big Eastern cities and little Southern towns, on boats off any shore and in cabins at the heart of any forest. But it seems somehow more wrong when it happens in a place Americans think of as their last pristine wilderness. There's a disconnect between what they accept as commonplace in Detroit or Miami or Chicago and what Outsiders want to believe about Alaska.

The truth is, most Alaskans came here from somewhere else and they brought their bad habits with them.

We born-again Alaskans like to put on airstalk about how tough the weather is here and call ourselves pioneers even though the kind of pioneering that confers bragging rights ended with World War II. The truth is, most of us are ordinary peoplegood and bad, brave or frightened, successful or not, flawed in the ways we all learn to live with.

Alaskans use a rough code to describe the different kinds of people who have been drawn north to what was until the mid-twentieth century little more than a sparsely settled outpost. There are the tree huggers; the rape-and-ruiners; the new-lifers; and the end-of-the roaders.

Tree huggers are people seeking escape from cities: outdoor types like mountain climbers and hikers, or serious adventurers who want to relive the pioneer experience, to build a cabin, haul water, smoke fish, live simply. Or they can be people who are simply tired of breathing smog. They come for what we have most of, the outdoors.

Rape-and-ruiners are, in unkind shorthand, those who come north to make money, to mine or construct or drill or sell. During the building of the trans-Alaska pipeline, thousands of these questers flooded into Anchorage each month. They tend to go back where they come from after a few years.

New-lifers are people dissatisfied with the life they made somewhere else. They are looking to start over where there's less competition and more room to take a chance. As a restaurant owner in Nome once told me: "All the big-wheel spokes back home were taken. If you wanted to be somebody, you had to wait for someone to die, and then there were dozens of others looking to take his place."

End-of-the-roaders are a different breed. You will meet a lot of them in Tom Brennan's murder chronicles. These are people who have worn out their welcome everywhere they've been, who have fled or been chased to the edge of the worldas far away from home as they can drive and still be an American.

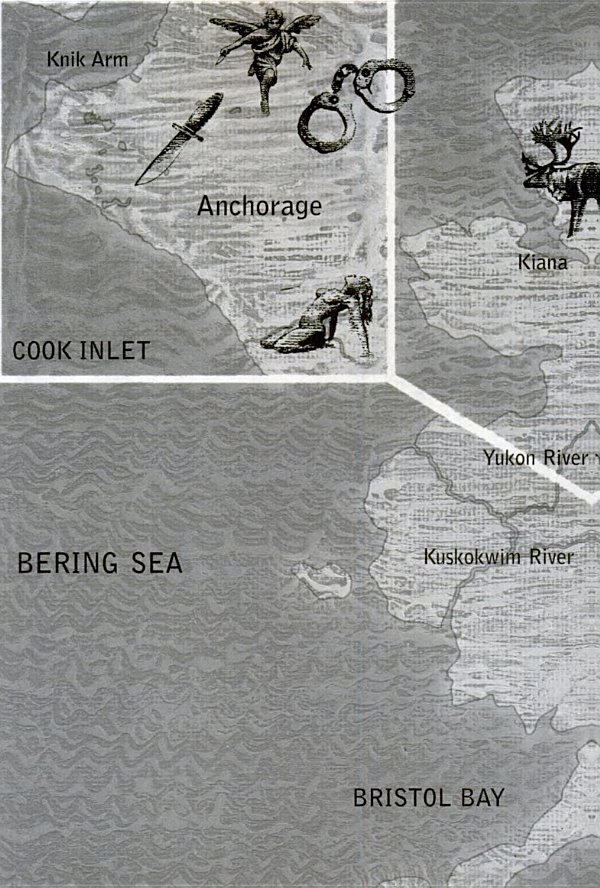

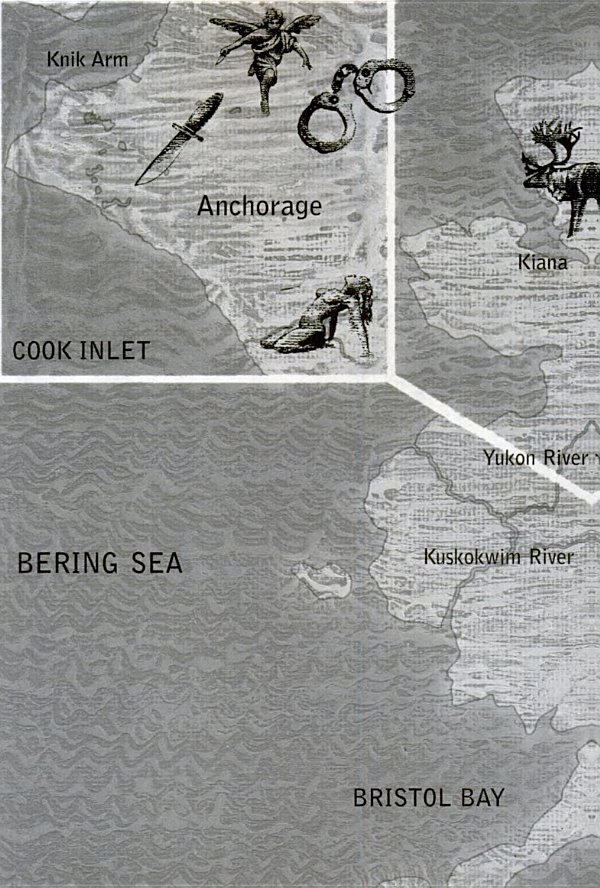

Sometimes they are fleeing law enforcement, like Kirby Anthoney, who was suspected of raping a teenager in Twin Falls, Idaho, and leaving her for dead. He moved to Anchorage to start over, living for a time with relatives. You'll find out how he repaid his aunt and uncle for their kindness. Robert Hansen, a nerdy baker who liked to hunt and could fly a plane, fled his Midwest criminal history but never lost his taste for hookers. Once in Alaska, he established a successful business, bought a nice home, and started a family. He also murdered at least seventeen women, many of them prostitutes.

Some end-of-the-roaders are loners who understand that they don't do well in normal society. Even in Alaska they flee cities like Anchorage and Fairbanks, hoping to outrun their own anger or mental illness, to live without the irritant of other human beings. A lot of these people succeed but many can't run far enough or fast enough. Louis Hastings sought refuge in a defunct mining town, then shot most of his neighbors. Michael Silka managed to murder seven people along a river bank 120 miles from Fairbanks before people noticed that their friends were disappearing.

Yes, husbands and wives kill each other in Alaska, just as they do everywhere. Drug dealers punctuate their commercial disputes with bullets. Gang wannabes shoot rivals from cars, and drunks brawl to the death. Brennan doesn't write about these commonplaces.

Murder fueled by drunken anger or dope is rarely interesting. It doesn't illuminate the frightening ways the human soul can warp. How could fourteen-yearold Winona Fletcher fire a bullet into a seventy-yearold woman begging on her knees for her life? She's never answered the question and it's unlikely we'll ever know for sure. "How could you," and "why would you" are life's real mysteries.

Most of the killers in these stories came to Alaska from somewhere else, perhaps with the same dreams of a better future as the rest of us. But their path led instead to death or a prison cell.

Sheila Toomey Anchorage

Sheila Toomey has reported on crime in Alaska for 20 years. Her work appears in the Anchorage Daily News, on the Scripps Howard News Service and at www.adn.com.

PREFACE

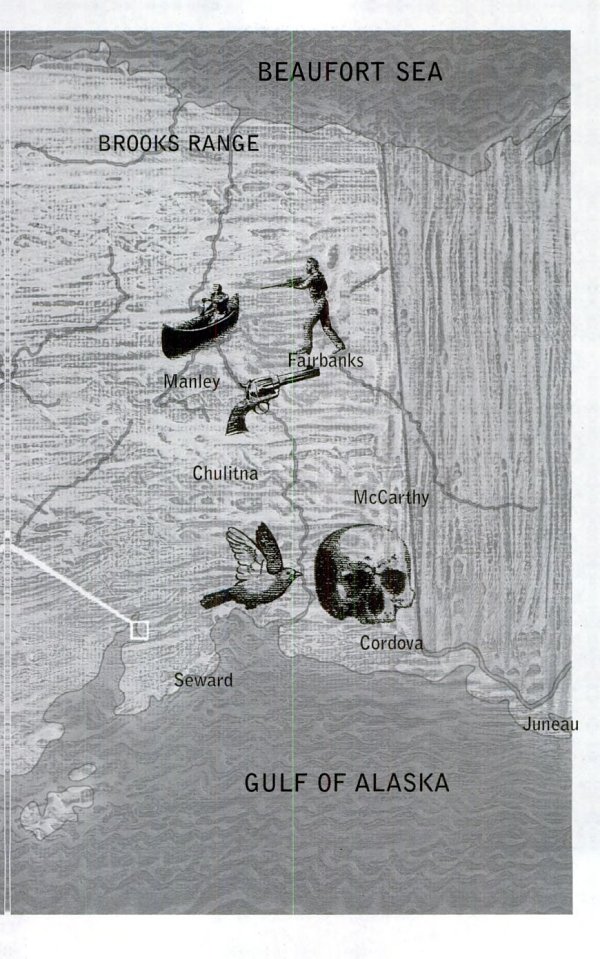

The research and writing of this book put me in fearful proximity to the dark side of Alaska. Living here, it's easy to accept the popular view of Alaska as a place defined by its magnificent scenery, abundant wildlife, and serenity. But the hard fact is that Alaska is also a place where passion, alienation, or dementia can result in sudden, violent death. The proof lies in these ten stories of murder most foul.

Alaska's climate played a role in some of these cases, as did the state's remote location. Extreme cold, long winter nightseven the continuous sunlight of summercan affect the minds of those living on the emotional edge. Many of the murderers described here were misfits who retreated from civilization to build new lives in the wilderness, but found the North Country even harder to handle than the societies they left. Eventually the misfits exploded and people died.

These are uniquely Alaskan murder cases, from the novice hunter who goes berserk when the thermometer hits rock bottom, to the pilot and serial killer who flies his victims into the wilderness, rapes and kills them, then buries their bodies in tundra and gravel river bottoms. One killer is a young man who comes to the territory at the turn of the twentieth century to build a railroad, kills a man who attacks his lover, and eventually becomes known to the world as the Birdman of Alcatraz.

The cases range from individual crimes of passion to explosive mass killings and cold-blooded serial butchery. The stories are true and readers may find the details shocking. I was first introduced to Alaska crime in 1967 when I left the Worcester, Mas sachusetts Telegram to become a reporter and columnist for the Anchorage Times.

Most of the crimes described here occurred during my many years in Alaska, and I followed each story as it unfolded day by day.

I thought I knew what the killings were all about until I began trying to re-create what happened, putting myself in the shoes of the murderers and their victims. That proved to be a chilling experience beyond all expectation. Immersing oneself in a crime, looking into the minds of those who hate intensely and imagining the fear and horror of the soon-to-die, proved to be unsettling in a way I could not anticipate.