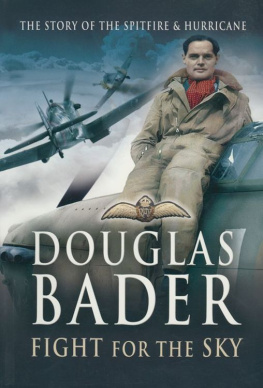

Reach for the Sky

The Story of Douglas Bader,

Legless Ace of The Battle of Britain

Paul Brickhill

To Thelma

Chapter 1

When Douglas Bader was nineteen, his flying instructor said, That young man will either be famous or be killed. It seemed simply a matter of which would happen first, there being no likely alternative, and the odds were on the former.

Right from the start Baders life had followed no placid formula. In 1909 the doctor warned Jessie Bader during her second pregnancy that the baby might not be born alive and that it would be risky for her to go ahead with it but, rather imperiously, she resisted any interference. A tall and strikingly attractive girl of twenty with a cloud of black hair piled in thick Edwardian waves, Mrs. Bader was often emotional and usually wilful. Outspokenness was the one noticeable quality she possessed in common with her husband.

She was seventeen when she met Frederick Roberts Bader (pronounced Bahder) at Kotri in the hot, dry plains of what is now Pakistan, and she was eighteen when she married him. He was twenty years older, a gruff, heavily moustached engineer, an almost confirmed bachelor captivated by the vital girl. A year later the first baby, Derick was born, and within a year all three were on their way back to England where Jessie could have the second child in greater safety.

The doctor and the midwife came to the house in London on February 21, 1910, and it was several hours before the danger was over and the baby successfully delivered. They named him Douglas Robert Steuart.

Three days later both Jessie and the baby caught measles, and as soon as she was better Jessie had to have a major operation. From the start mother and baby were almost completely separated. Jessie recovered, though she had no more children, and then the family had to return to India. Douglas was only a few months old; too young, they thought, for Indias climate, so they left him with relatives in England.

He was almost two by the time he was taken out to join the family and that may have been the beginning of the loneliness that has been deep within him ever since. He was a stranger in India, like an affectionate puppy before it has been smacked for wetting the floor. Derick had been receiving the attention lavished on an only child and the new boy did not fit in. For some time his face was covered with little sores; they found that Derick had been pinching bits of skin off.

Six months later servants were constantly on duty to keep them apartDouglas had begun fighting back like a tiger. It seemed that he had inherited the bold vigor of his parents. From then on he always fought his own battles and never cried if he lost: the only times he cried were when his parents and Derick went visiting and left him behind, which they often did.

In 1913 the family returned to England and the following year, when the war came, Frederick Bader went with the Army to France. It was almost the last time Douglas saw his father. In the years 19141918 the small boy had his own war to fightusually against Derick and adult authority. As a rule he could hold his own in the scuffles with Derick but when crises had to be resolved by parental judgment, Derick had an advantage: in Jessies indulgent eyes he could do no wrong. Douglas, on the other hand, was regarded as incurably naughtyinevitable result of a struggle for recognition. Basically he was impulsively full of life and prone to jump at any challenge to win respect. He became combative only when affairs threatened his amour propre, and was therefore often combative. Yet his Aunt Hazel, who showed him affection, was touched by his warm-hearted devotion.

At preparatory school he had his first fights outside the family, and they were always with bigger boys. Always the same story: bigger boys expect smaller boys to know their place and Douglas would not be forcibly put there. He never lost a fight, though he fought several bloodstained drawsthen the generosity showed because he had a tendency to stop fighting when he had hurt someone. The climax came when a bigger boy twisted his ^ arm to exact respect and collected a clout across the face from the victims free hand. In the fight that followed Douglas, exalted by fury, scored his first knock-out and thereafter was left in comparative peace.

Then school games gave him the outlet his mettlesome spirit needed. Soon he was easily the youngest in the school rugby football team, a gritty and indestructible small boy bouncing up as fast as he was knocked down, and loving it. In the classroom his customary enthusiasm was noted only by its absence. He was obviously intelligent but he did not like study; therefore he declined to bother with it and no one could make him.

The war was already over when his father, still in France, died of an old shrapnel wound in the head. The boys emotions were little affected; he had hardly even known his father. A more practical effect was that there was not enough money now to send him on to public school, that essential prerequisite to success in the lives of Englands upper-middle class. A scholarship was the only answer. For his own good, then, he had to study: therefore he studied.

Not for a moment did he slacken his sporting activity. In that last year he was captain of football, captain of cricket, and in the school sports won every senior race he was allowed to enter for. He also won his scholarship.

About this time Jessie re-married; her new husband was a mild Yorkshire clergyman, the Rev. William Hobbs, who was swiftly and rudely awakened by his intransigent new family. With Jessies approval he instituted family prayers after breakfast each morning but the scuffles and giggles of Douglas and Derick robbed the occasions of reverence. Douglas was packed off for a week with Aunt Hazel and her husband, Cyril Burge, who was adjutant of the Royal Air Force College at Cranwell (the equivalent of West Point).

Seeing aeroplanes at close quarters for the first time excited him greatly and he stood for hours in Surges garden watching the cadets jockey the quivering wood and fabric biplanes round the circuit. (It was 1923, long before the age of sleek monoplanes.) Burge excited him further with stories of flying in the war, and was attracted by the boy who seemed at times almost on fire, a good-looking youngster with large, frank eyes, a mouth that grinned easily, crisp, curly hair and a square jaw, an oddly commanding face for a small boy. Burge thought he had injected the flying bug into Douglas, but if so the bug was dormant because a few weeks later the boy went on to St. Edwards School near Oxford and virtually forgot everything else but games.

St. Edwards was accepted as one of the good schools and had vast acres of playing fields. By 1925, when he was fifteen, Bader was the youngest player in the school cricket team, and at the end of the season had the best batting and bowling figures. He also set up a new school record for throwing the cricket ball (well over 100 yards). But it was the winter he was waiting for; he liked the aggressive rough and tumble of rugby football above everything. When the school team was pinned on the board and he saw his name there (again the youngest member) it gave him the sharpest moment of joy. A school report of a match soon after said, Bader did as he liked and scored seven times.

No question now of him being second to Derick, or second to anyone else. The headmaster, the Rev. Kendall, has never forgotten Baders jaunty figure striding round the quadrangle, hands in pockets, absolutely full of beans. Some people thought he was getting a little bumptious, but for the first time in his life he really had status in the hierarchy of his world encircled by the stone walls of the school. That was his world. The other home, in Yorkshire, was little more than an occasional stormy interlude experienced during vacations.

Next page