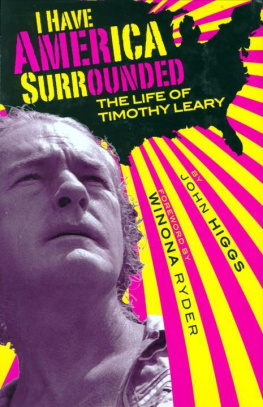

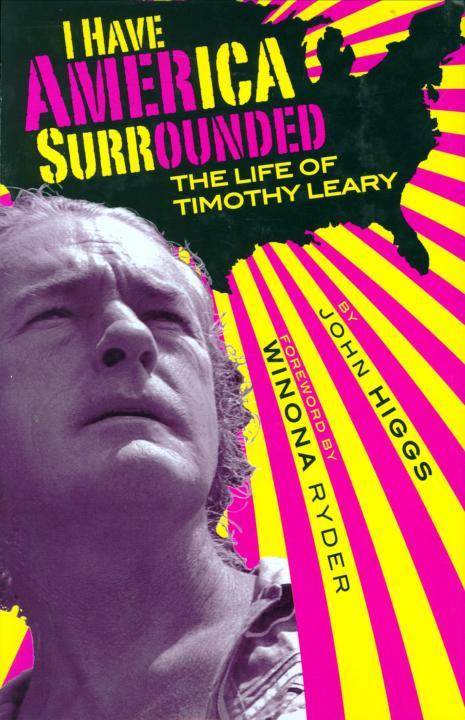

The Life of Timothy Leary

xi

i i

-KAKUZO OKAKURA, The Book of Tea

by Winona Ryder

HREE MONTHS AFTER I was born, my dad, who was Tim's archivist, went to see him in Switzerland, where Tim was living in exile after escaping prison and being called "the most dangerous man in the world" by Nixon, who was furiously trying to hunt him down.

HREE MONTHS AFTER I was born, my dad, who was Tim's archivist, went to see him in Switzerland, where Tim was living in exile after escaping prison and being called "the most dangerous man in the world" by Nixon, who was furiously trying to hunt him down.

My dad and Tim took acid and went skiing, and my dad pulled out a picture of me-the first one ever taken (I was a day old)-and showed it to Tim and asked if he would be my godfather. Tim said: "Sure."

We didn't meet until seven years later, after Tim was released from prison and came to visit us on our commune in Mendocino County. We were walking along a dusty road on a remote mountain ridge. It was sunset and we were holding hands. I looked up at him and said: "They say you're a mad scientist."

Tim smiled and said: "I know." I think he liked the sound of that.

Around the time I became a teenager I wanted to be a writer. This, of course, thrilled Tim and we constantly talked about books. My favorite literary character was Holden Caulfield; his was Huck Finn. We talked about the similarities between the two characters-especially their feelings of alienation from polite society. I wanted to catch all the kids falling off the cliff and Tim wanted to light out for the territory. It was a time when I was in my first throes of adolescence and experiencing that kind of alienation. And talking to Tim was the light at the end of the tunnel.

He really understood my generation. He called us "free agents in the Age of Information."

What I learned from Tim didn't have anything to do with drugs, but it had everything to do with getting high. His die-hard fascination with the human brain was not all about altering it, but about using it to its fullest. And he showed us that that process-that journey-was our most important one. However we did it, as long as we did it. "You are the owner and operator of your brain," he reminded us.

Tim was a huge influence on me-not just with his revolutionary ideas about human potential, but as someone who read me stories, encouraged me, took me to baseball games-you know, godfather stuff. He was the first person outside my family-who you never tend to believe while growing up-to make me believe I could do anything. He had an incredible way of making you feel special and completely supported.

F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote a letter to his daughter in which he said that he hoped his life had achieved some sort of "epic grandeur." Tim's life wasn't some sort of epic grandeur. It was flat out epic grandeur.

It's easy sometimes to get lost in all the drug stuff that Tim's famous for-all the "Turn on, tune in, and drop out" stuff, especially in a society that loves a sound bite. But it wasn't Tim's only legacy. It was his vitality, enthusiasm, curiosity, humor and humanity that made Tim great-and those are the real ingredients of a mad scientist.

Delivered at Timothy Leary's memorial service, June 9, 1996, Santa Monica CA

HE SIGNAL THAT the jailbreak could go ahead was a telegram. It arrived on the afternoon of Friday, September 11, 1970, while Dr. Timothy Leary was exercising in the prison yard. He was called into the control office and handed a slip of yellow paper, which read:

HE SIGNAL THAT the jailbreak could go ahead was a telegram. It arrived on the afternoon of Friday, September 11, 1970, while Dr. Timothy Leary was exercising in the prison yard. He was called into the control office and handed a slip of yellow paper, which read:

BELOVED

OPERATION TOMORROW DOCTORS FEEL BEST NOT TO WAIT TOTALLY OPTIMISTIC ABOUT SUCCESS AND NEW LIFE DON'T WORRY ILL BE BRAVE WON'T BE DOWN TO VISIT SUNDAY BUT WE'LL BE TOGETHER SOON I AWAIT YOU I LOVE YOU CONTACT ME AT THREE TREE RECOVERY CENTER.

YOUR MATE

The sergeant who had handed him the telegram had done so with a look of sympathy. The message was from Tim's wife Rosemary, and inmates always reacted badly to canceled visits. Tim nodded and kept his face blank.

The telegram confirmed that arrangements for the necessary cars, drivers, safe houses and fake identity papers were complete, and that the "operation" could go ahead the following night. The "three trees" mentioned at the end of the telegram referred to the rendezvous. This was a group of trees, joined at the root, which stood a few hundred yards outside the penitentiary. If Tim could get himself outside the prison and reach the three trees, he would find a car waiting to take him to freedom. The symbolism was ideal, for Leary had Irish blood, and a group of three trees, always in fruit, was a symbol of unstoppable life in ancient Irish myths.

The stakes were high. If he did not reach the trees there was little hope that he would ever be a free man. Leary had just been informed that he would be flown to Poughkeepsie in New York State the following week, where he would face further charges relating to the raid on his house in Millbrook nearly five years earlier. The likelihood of receiving more jail time was strong. This would destroy any hope that he had of escape, for this extra time would almost certainly trigger a transfer to a higher security prison. If he was to break out, it was Saturday or never. But that Friday, the sky was a brilliant blue. His plan needed a foggy night in order to succeed. Without fog, there would be times during the escape that he would be silhouetted in the sights of the gun trucks and the armed guards. Without fog, only a miracle could prevent him from being shot.

He spent the following afternoon in the television room, watching the Stanford-Arkansas football game, and returned to his cell for the 4 p.m. head count. At 4:30, the whistle blew to signify the end of the count, and he waited for his cellmate to go to the food hall. Tim declined to join him, saying that he had eaten on the early line. The moment that his cellmate left, he got to work.'

Next page

![Robert Greenfield - Timothy Leary: A Biography [excerpts]](/uploads/posts/book/113331/thumbs/robert-greenfield-timothy-leary-a-biography.jpg)

HREE MONTHS AFTER I was born, my dad, who was Tim's archivist, went to see him in Switzerland, where Tim was living in exile after escaping prison and being called "the most dangerous man in the world" by Nixon, who was furiously trying to hunt him down.

HREE MONTHS AFTER I was born, my dad, who was Tim's archivist, went to see him in Switzerland, where Tim was living in exile after escaping prison and being called "the most dangerous man in the world" by Nixon, who was furiously trying to hunt him down.

HE SIGNAL THAT the jailbreak could go ahead was a telegram. It arrived on the afternoon of Friday, September 11, 1970, while Dr. Timothy Leary was exercising in the prison yard. He was called into the control office and handed a slip of yellow paper, which read:

HE SIGNAL THAT the jailbreak could go ahead was a telegram. It arrived on the afternoon of Friday, September 11, 1970, while Dr. Timothy Leary was exercising in the prison yard. He was called into the control office and handed a slip of yellow paper, which read: