Timothy Leary: Outside Looking In

EDITED BY ROBERT FORTE

Park Street Press

Rochester, Vermont

Light is the language of the stars and the sun where we will all meet again.

Timothy Leary

May 30, 1996

Acknowledgments

T his book was born of many labors. Though it bears my name as editor, without the guidance, collaboration, and friendship of Frank Barron, Greg Bogart, Nina Graboi, Michael Horowitz, Rowan Jacobsen, Marge King, Becky Leuning, Vickie Marshall, Ralph Metzner, and Rosemary Woodruff, in particular, it might have remained only a good idea. Thank you to Heather Laudadio for helping me conceive this work. A special thank you is due to the folks at Drive Savers in Novato, California, for the text of the book suffered not one, but two hard-drive crashes when it was just about complete. All seemed lost till their expert service saved the day. Thanks and love to the family and friends that surrounded Tim in his final months for welcoming me into their home, for making me feel part of the team, especially Camella, Chris, Joe, Zach, Michelle, and Carol. Let us always be friends. Thanks to my own family, especially my father, Robert Forte Sr., an arch republican, for proving that blood is thicker than ideology, and for financial support. Thank you to Jaime Nelson for her nourishing, love-filled spirit. Gratitude to my son, Mircea Alexander Forte, who, seven years old when Tim died, got right to the point when he asked, Dad, why was Timothy so famous anyway? What did he dofree the slaves or something? And finally, to Timothy Francis Leary, thank you for the privilege to share in your abundant and eternal life.

Res ipsa Loquitur

(let the good times roll)

Introduction

ROBERT FORTE

There is an ancient axiom, which runs: the more bitterly and acutely we formulate a thesis, the more irresistibly it clamours for the antithesis.

Hermann Hesse,

Magister Ludi

Timothy Francis Leary was one of the most influential people of the twentieth century. What his influence has been, however, remains to be determined. Leary is loved and castigated for his spirited popularization of psychedelic drugs in the 1960s, surely his grandest achievement in a lifelong mission to joust with authoritarianism wherever he encountered it. This book is not a biography of Leary, nor an in-depth study of his ideas. Think of it as a mosaic of flashbacks and reflections, mostly in tribute to this mercurial character and the celebrated role he played as a leader of a social, philosophical, and religious movement. The book was conceived one December morning in 1993 as I set out to visit Tim at his home high in the Beverly Hills of Los Angeles. I had just returned from a conference on LSD in Switzerland that was convened by Sandoz Pharmaceuticals Company and the Swiss Academy of Medicine50 Years of LSD: State of the Art and Perspectives on Hallucinogens. That meeting began with the president of the Swiss Academy, Alfred Pletscher, first lauding the extraordinary scientific potential of LSD and then declaring:

Unfortunately, LSD did not remain in the scientific and medical scene, but fell into the hands of esoterics and hippies and was used by hundreds and thousands of people in mass gatherings. This uncontrolled propagation of LSD had dangerous consequencesfor instance, prolonged psychotic episodes, violence and suicide attempts. Therefore, the use of this drug was subjected to severe restrictions by legal acts. (Pletscher and Ladewig, 1994)

Whenever Learys name was mentioned at this conference, it was with a dismissive and scornful tone by the predominantly psychiatric researchers attending, for it was generally held that Learys exuberance and the resultant publicity over psychedelics prompted the legislation that forbade their use.

Of the myriad dysfunctional aspects of U.S. drug policy, none is more bizarre and un-American than the illegal status these drugs hold. Aldous advocated a cautious boldness, wrote Humphry Osmond, advising the explorers to do good stealthily and to avoid publicity. Unfortunately his good counsel was not always taken. If Leary had been more circumspect perhaps these rediscovered ancient sacraments could have been more gradually and effectively integrated into our society. Did Leary and company provoke this terrific irrational phobia of psychedelic drugs, or anticipate it and vault clear over it to spread the word? Legal research of these substances is still paralyzed by mounds of red tape. Meanwhile millions already know that beyond the fears of state-sanctioned psychiatry and governmental policy, under the right set and setting, psychedelics can lead to joy, mystery, rebirth, and realization beyond belief. Seven million people I turned on, Leary said near the end of his life, and only one hundred thousand have come by to thank me.

Of course the social gyrations of the 1960s renaissance of spirit are far too complex to lay on one man but Leary, clearly, was a most visible figurea brilliant, charismatic, funny prophet; a groundbreaking social scientist; a poet; a fame-seeking, careless, self-important, self-destructive fool; or a scapegoat, depending on your perspective.

You get the Timothy Leary you deserve, he once said.

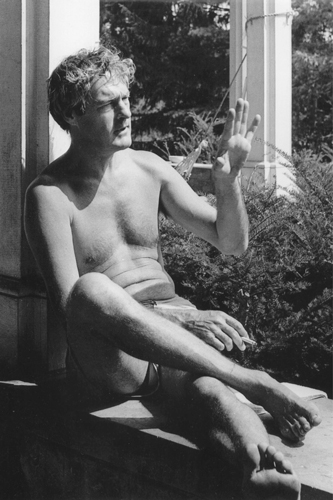

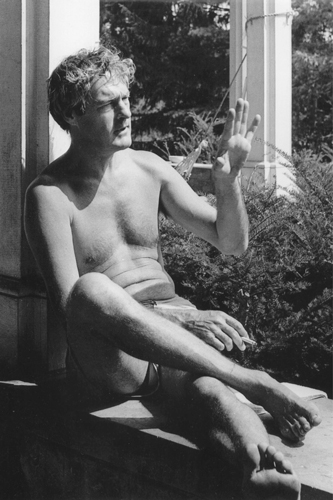

Mother and Aunt Mae

Timothy Leary was born on October 22, 1920, in Springfield, Massachusetts, the only child of Timothy and Abigail Leary. His grandfather, reputed to be the richest Irish Catholic in western Massachusetts, was perceived by young Timothy as a majestic patriarch who valued literacy and the arts. The only meaningful words his grandfather ever spoke to him were, Never do anything like anyone else.... Find your own way.... Be one of a kind.

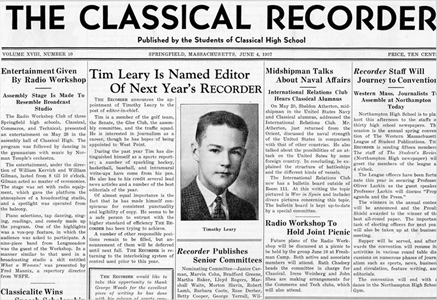

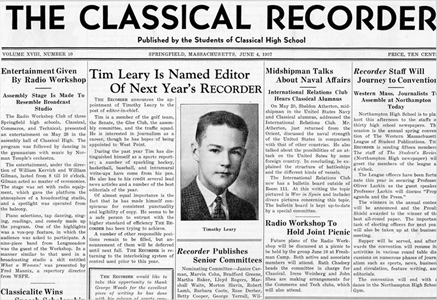

In high school

Tims father was an army dentist, an apparent heir to the Leary fortune, and a drunkard who used to beat his young son. But the fortune, it turned out, was depleted by the depression and assorted other indebtedness. On the very day this was learned, Timothy Learys father gave his twelve-year-old son a hundred dollar bill, left the house, and never returned. Raised by a devout Catholic mother and his spinster Aunt Mae, Timothy Leary became a distinguished, highly spirited, and rebellious teen. He rejected the school motto, the Kantian imperativeNo one has the right to do that which if everyone did would destroy societyby writing what he called a particularly fiery editorial suggesting that the Categorical Imperative was totalitarian and un-American in glorifying the welfare of the state over the rights of the individual, earning him the disdain of the schools principal and no recommendation to college. As a favor to his mother the Monsignor enabled his admission to Holy Cross, a spartan Jesuit school in nearby Worcester, Massachusetts, where he excelled as a studentand as a bookie, who had his way with the shop girls downtown. He lasted a year at Holy Cross. After scoring the highest mark on the examination for the service academy, he entered West Point in 1940, proud and eager to serve his country as an elite military officer. But after three months Leary ran afoul of the West Point regime. He was caught drunk and admitted providing liquor to underclassmen while returning from the Army-Navy game. Refusing to resign, he was punished by silencing, an ordeal that forbade him to speak or be spoken to by any of his classmates for the duration of the year. In letters to his mother at this time, he poured out his soul:

Next page

![Robert Greenfield - Timothy Leary: A Biography [excerpts]](/uploads/posts/book/113331/thumbs/robert-greenfield-timothy-leary-a-biography.jpg)