Contents

BLACK AND WHITE PHOTOGRAPHS

Bonobos stand tall, and often mate face to face

If A AT were true, we would be more streamlined. More streamlined than what?

Apart from the pachyderms, the only naturally naked land mammals are Homo sapiens and the naked Somalian mole rat.

... the people look at the sea

LINE ILLUSTRATIONS

The Turkana Basin

The Afar Triangle

Bipedalism was not always a rare form of locomotion

Proboscis monkeys

Measurements of relatedness between primates

Pachyderms

The Venus of Willendorf

Comparision of adipocytes in humans and other mammals

The function of the lachrymal nerve

Skin glands in humans and other mammals

Patas monkey

The larynx in humans and gorillas

The palate and dorsal wall of dasyurus, lemur, human embryos

The uvula and the human palate

Registration of thoracic movements during an apnoeic episode

Adaptation to diving

Hair tracts in apes and humans

Young proboscis monkeys

The philtrum

TABLES

1Palaeoenvironmental reconstructions of early hominid localities in Africa

2Comparative energetic costs of walking for quadrupedal chimpanzee and bipedal human at normal travel speeds

3Cases of observed bipedal standing or movement

I owe gratitude to more people than I can remember for information, references, answers to questions, and general advice over the years. Hundreds of communications came from general readers who sent letters of appreciation, queries, ideas, and cuttings. I would like to thank them all.

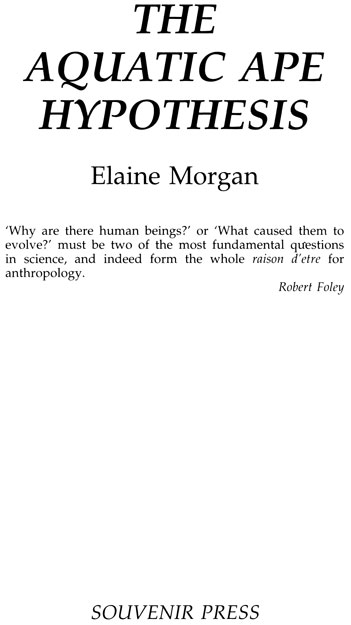

Among the scientists who supplied comments, information, advice, or permission to use their material, I would like to thank the following (inclusion in this list does not imply any degree of agreement with the aquatic hypothesis): Leslie Aiello, Sir David Attenborough, Michael Chance, Bruce Charlton, Michael Crawford, Stephen Cunnane, Richard Dawkins, Frans de Waal, Christopher Dean, Daniel Dennett, Derek Denton, Robin Dunbar, Derek Ellis, Peter Rhys Evans, Karl-Erich Fichtelius, Robert Foley, John Gribbin, David Haig, Kevin Hunt, Chris Knight, Robert Martin, Desmond Morris, Michel Odent, Caroline Pond, Vernon Reynolds, Graham Richards, P. S. Rodman and H. M. McHenry, Erika Schagatay, Phillip V. Tobias, Marc Verhaegen, Peter Wheeler, Tim White.

I appreciated the opportunity of debating AAT for several months on the Internet. My thanks are due to those who supported me, and to those of my opponents who were constructive in their criticism and generous in sharing their specialist knowledge.

My thanks also to: Amanda Williams, who drew the pachyderms and the proboscis and patas monkeys; Frans de Waal, for the bonobo photographs; Jessica Johnson and Michel Odent for the water baby photograph; Dr Terence Meaden and June Peel for the drawing of the Venus of Willendorf; Brooks Krikler Research for picture research.

This book, like the others I have written, is addressed primarily to the general reader, so I have tried to use plain and accessible language.

This time, however, I have included numbered references. After disputing for 25 years with professional scientists, I have learnt to respect the high standards they set themselves, and expect from others, in identifying their sources.

The references are unorthodox in one respect: a small percentage does not relate to the written word. The study of natural history owes a considerable and growing debt to the camera crews who travel the world recording the behaviour of rare species in inaccessible places. It is time that this material was accorded, as source material, equal status with the observations of a scientist with a notebook.

The idea on which this book is based does not qualify as a theory in the strict Popperian sense adopted by scientific philosophersit is more accurately a hypothesis. But the acronym AAT (Aquatic Ape Theory) has been in use for so long that it would be confusing to change it now.

I hope that the book will be as enjoyable to read as it was to write.

1

We are back to square one.

Phillip Tobias

The question

It is generally agreed that around eight or nine million years ago there lived in the forests of Africa an animal known to anthropologists as the last common ancestor (l.c.a). The descendants of the l. c. a. split into different lineages, and their extant survivors are gorillas, chimpanzees, bonobos and humans. Of these, humans differ more markedly from the African apes than the apes differ from one another. There are numerous and striking physical differences, and at least some of them began to appear either at the time when the human lineage diverged from that of the other apes, or very shortly afterwards. It would seem reasonable to conclude that something must have happened to our ancestors which did not happen to the ancestors of the other apes.

The question at issue is simply: WHAT HAPPENED?

Twenty years ago, that was regarded by anthropologists as a pertinent question, and most of them were convinced that they knew the answer to it. Today that confidence has so far evaporated that some of them query whether an answer to it is possible or even desirable. In 1996, the title of a public seminar in London was Do we need a theory of human evolution?

The savannah-based model

The explanation current in the 1960s was very clear and straightforward. The divergence between apes and humans was said to be due to climatic changes which resulted in the dwindling of the African forests and the rapid expansion of a grassland eco-systemthe African savannah.

The apes, it was concluded, are descended from the populations of the last common ancestor that remained in the trees, whereas humans are descended from populations which were driven out of the shrinking forests and forced to make a living on the savannah. A minority version claimed that they were not victims but pioneers, who opted to move out to a more exciting and potentially rewarding life on the plains. In both versions the change of venue was held to account for the adaptations specific to the hominid line, such as bipedalism and nakedness and, in the longer run, to tool-making, increased intelligence and verbal communication.

It has been repeatedly asserted (for example, on the Internet) that there was never such a thing as the savannah theory, that it was simply a straw man constructed by Elaine Morgan for the pleasure of knocking it down again, and that no reputable scientist can be shown ever to have used the phrase savannah theory. The last part of the statement is perfectly true. I would no more have expected them to use that phrase than I would expect a Creationist to refer to the God theorytheir faith in it was too strong for that.

But the savannah-based model was no straw man. Raymond Dart, who discovered the first African hominid fossil (the Taung baby), on what is now the veldt, believed that the harsh conditions on the savannah turned the first hominids into hunters and killers, and that this was the driving force that made us human.

The savannah scenario was embraced from the beginning with enthusiasm. Lyrical popularisers like Robert Ardrey exulted in it: We accepted hazards and opportunities and

Clues to the origins of the human social order were increasingly sought in the behaviour of savannah species like the baboon, as researched by Irven de Vore.

In 1987, looking back on the earlier years, Randall L. Susman described it as follows:

Next page