Copyright 2003 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 Williams Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 3 Market Place, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1SY

All Rights Reserved

Second printing, and first paperback printing, 2004

Paperback ISBN 978-0-691-12028-7

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

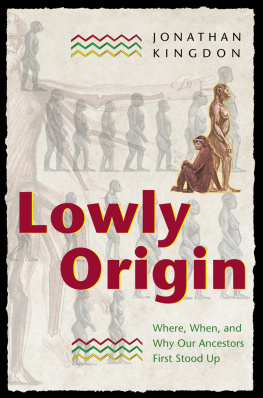

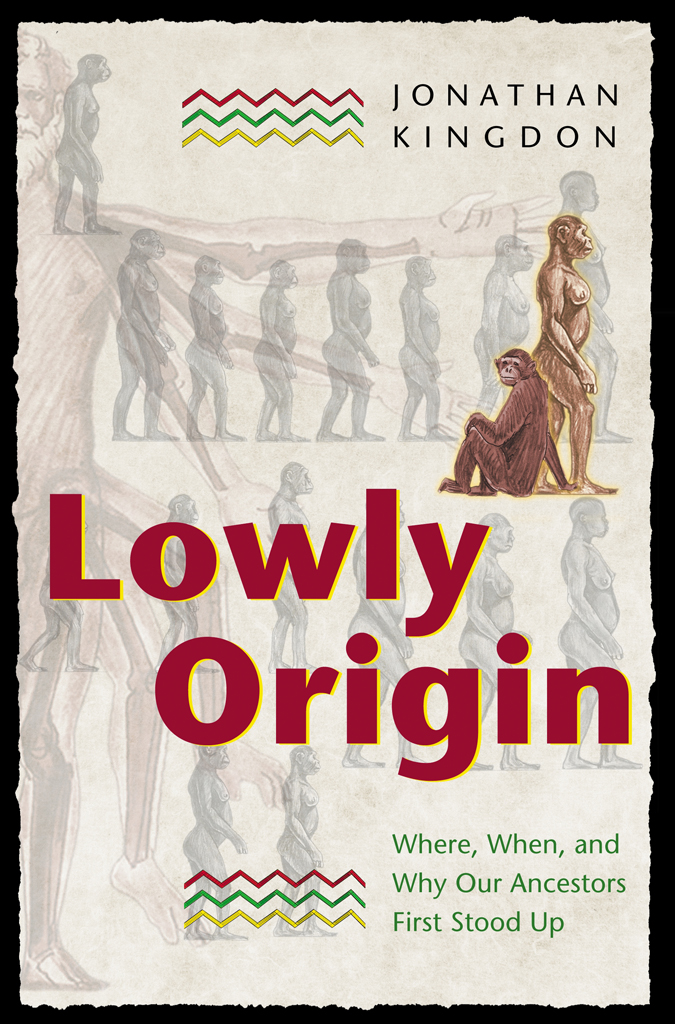

Kingdon, Jonathan.

Lowly origin : where, when, and why our ancestors first stood up / Jonathan Kingdon.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-691-05086-4 (cl : alk. paper)

eISBN 978-0-69122-344-5 (ebook)

1. Fossil hominids. 2. BipedalismOrigin. 3. Human beingsOrigin. 4. Human evolution. I. Title.

GN282 .K54 2003

599.938dc21 2002072852

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

R0

To Minnie, Dorothy, Elena, and Afra.

Much loved mothers, and

All their Sisters.

List of Figures

.

List of Tables

Acknowledgments

W hen my parents took me, as a very small boy, to Olduvai Gorge and to the nearby giant crater of Ngorongoro, none of us could have foreseen what an enduring influence these eroding plains and volcanoes would have on my later life and work. Nor could we have anticipated how a few months in Natal and frequent family holidays on the East African coast and its hinterland (from Lamu to Mtwara) would later help shape my thinking about human evolution. Readers will not have to cover many pages to appreciate how many of the ideas in this book are informed by a life lived in places that are haunted by the bones of extinct beings yet also alive with living fossils.

Nonetheless, it has to be people, their discoveries, their enthusiasms, their visions, and their published ideas that have inspired me and driven this book to completion. Over several decades of living in Africa, Asia, Europe, Australia, and America, I have been extraordinarily privileged to have met an inspiring diversity of scientists and naturalists. In the depth and range of their minds and in the generosity of their intercourse I have found the means and the courage to attempt a new account of bipedal origins while simultaneously exploring the saga of my own origins as a representative but singular human animal.

Few of those who first inspired me are still alive. However, impressions are often at their most intense and fresh in youth, and this is the place to remember and acknowledge where and whence primary enthusiasms and influences began. Of those directly relevant to the theme of this book, I fondly remember Dorothy and Teddy Kingdon, Bill Bishop, Reg Moreau, Julian Huxley, Desmond Vesey Fitzgerald, Hugh Elliot, Francois Bourliere, L.S.B. and Mary Leakey, Peter Miller, Max Costa, Philip Leedal, Phyl Ginner, Charles Jackson, and Sonia Cole.

I owe debts of gratitude to those that have inspired me with their own work and insights but have also examined, taken an interest in, or (sometimes without knowing it) helped shape some of the ideas in this book. Among them are Matt Cartmill, Yves Coppens, Richard Dawkins, Tim Flannery, Colin Groves, Mike Hammer, John Harris, Alison Jolly, Cliff Jolly, Adriaan Kortlandt, Bob Martin, Pat Shipman, Elwyn and Friederun Simons, Chris Stringer, and Caroline Tutin. I am especially grateful to Steve Wainwright, Alan Walker, Laura Snook, and Ryk Ward for their friendship, support, and critical interest. One Kampala evening, quite some years ago, my colleague Tag El Sir Ahmed urged me to write and illustrate a book about the human family. Self-made Man was my earlier response, but Tag will be surprised by this extension of that memory and by the lasting viability of the seed he planted. My family continue to be a source of support and stimulus.

It has been my privilege to participate in, share or simply observe the work of learned institutions in many countries. The Institute of Biological Anthropology and Department of Zoology at Oxford University have been my academic homes for many years, and I treasure my colleagues and my association with them. Earlier, Makerere University and the National Museum in Kampala, Uganda, provided home, inspiration, and dynamo for a particularly active and stimulating period of my life and career. At Chiromo, Nairobi University, my colleagues, especially Reino Hofmann and Malcolm Coe, always made me welcome and provided laboratory space and facilities. I have kept in touch with many of my Makerere and Nairobi colleagues. More recently, Duke University in North Carolina, Skidmore College in New York State, and Kyoto University in Japan invited me as Visiting Professor, all institutions where the work and ideas of new colleagues were both stimulus and influence in helping shape some of the themes in this book. In particular, I remember Shiro Kondo, Akira Suzuki, and Masao Kawai for their many kindnesses at the Primate Research Institute at Inuyama. Likewise, Knut Schmidt-Nielsen, Elwyn and Friederun Simons, Peter Klopfer, Dan Livingstone, Richard Kay, Lesley Digby, Carel van Schaik, and many others gave me the warmest of welcomes and much collegiate stimulus at Duke. While I struggled with the first draft of this book at Skidmore, Tad, Phyl, John, Kris, Kathy, Meganindeed, most of the facultymade my spell in Saratoga Springs a delight and also provided much practical assistance. I am grateful to Richard Leakey for a fellowship with the Kenya National Museums and, much earlier on, for less formal welcomes from Louis and Mary to view the research work of the then Coryndon Museum. Meave and Louise Leakey maintain, with equal distinction and outstanding grace, the splendid traditions begun by their family. All who work on human origins owe the Leakeys many thanks for their pioneering initiatives.

I have been a regular visitor to the British Museum of Natural History since boyhood and am grateful to Captain C.H.B. Grant and Robert Hayman for identifying my specimens and, among many others, Peter Andrews, Alan Gentry, and Chris Stringer for the opportunity to work and visit. For much shorter visits to the South African Museum in Pretoria, the Musee dHistoire Naturelle and Musee de lHomme in Paris, I remember Bob Brain, Elizabeth Vrba, Yves Coppens, Drs. G. and F. Petter, and Francois Bourliere with gratitude. Tim Flannery was my host at the Australian Museum in Sidney, and he and Mike Archer introduced me to the dynamic community of evolutionary biologists in Australia, an association facilitated by a research fellowship with C.S.I.R.O. in Atherton and Canberra. I have been the beneficiary of brief visits to the collections of the Museums of Natural History in New York, Washington, and Los Angeles, and I am grateful to many scientists there.

As a Scientific Fellow of the Zoological Society of London over many years, I have come to greatly value the Societys meetings, library, and collections. Likewise, the Royal Geographic Society has been the venue for many important projects, and I have been fortunate enough to have participated in several of their expeditions and other activities, both in London and abroad. Nigel and Shane Winser have been leading lights in all these initiatives and have also taken a personal interest in my own biogeographic and evolutionary enterprises. Over the years the Welcome Trust has been the principal supporter of my work on African Mammal and Primate evolution and the Atlas of Evolution in Africa. I remember my association with the Trust and its former director, Peter Williams, with respect, gratitude, and affection.