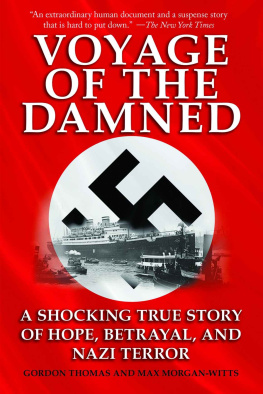

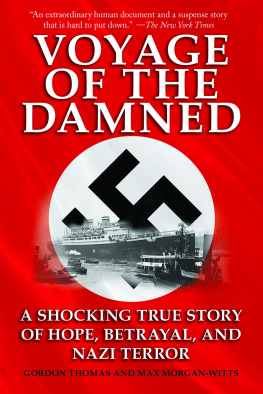

Universal Critical Acclaim For Voyage Of The Damned

Suspense, love, despair, unexpected acts of kindness mixed with treachery, Voyage of the Damned tells one of the most poignant stories in the long march to the furnaces of Hitlers Holocaust... an extraordinary human document and a suspense story that is hard to put down.

The New York Times

Riveting, written with passion, it should be widely read.

Publishers Weekly

Rich in detail... powerful in the writing.

El Pais

Everything about Voyage of the Damned has been touched with greatness.

New York Post

Detailed and meticulous, this admirable work is both an indictment and a thriller. One reads it with a mixture of excitement and anger.

Jewish Chronicle (USA)

Greed and isolationist world politics.

Jewish Times (USA)

Voyage Of The Damned

A Shocking True Story of Hope, Betrayal, and Nazi Terror

Gordon Thomas

Max Morgon-Witts

Copyright 2010 by Gordon Thomas and Max Morgan-Witts

All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 555 Eighth Avenue, Suite 903, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 555 Eighth Avenue, Suite 903, New York, NY 10018 or info@skyhorsepublishing.com.

www.skyhorsepublishing.com

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

9781616080129

Printed in the United States of America

Dedication

This book is dedicated to those who were the damned, on the St. Louis not only the passengers who are alive today and told their story to us, but all on board the ship, who were caught up in events they did not understand and could not control.

Those who survived the voyage and aftermath are today scattered throughout the worldNorth and South America, Great Britain, Australia, Europe, and, of course, Israel. And also Germany. Some are now wealthy, a few poor. Some still live in fear.

Almost everyone we approached was willing to meet us. One or two found that when the time came they could not bring themselves to recall and relive the experience. The minds of a few, in particular those who were young and impressionable in 1939, are now so cruelly scarred by what happened to them that their mental state led us, regretfully, to conclude their testimony was untrustworthy.

A few agreed to talk to us on condition that they not be quoted. We have respected this wish, understanding their desire for anonymity; what they told us was useful as background information and corroborative evidence. But they, and those unwilling or unable to meet us, were in the minority. For most, telling a stranger things they could hardly bring themselves to discuss with their closest friends seemed therapeutic, almost as if the experience was exorcised by the telling.

Inevitably, the passage of time, the insidious influence of propaganda, a confusion between what they have read and what actually happened, led some we interviewed to mix fiction with fact. We have tried to get around this by relying on interviews with survivors, crew members, and others directly involved with the voyage of the St. Louis, and consulting official archives, diaries, letters, and other eyewitness accounts written at the time.

Our responsibility to those living and dead was to tell the story as impartially and truthfully as the available sources and our combined talents allowed. Voyage of the Damned is not meant to be a crusading book, but it is, we hope, an honest and revealing one.

We thank especially those passengers whose names are listed below. Their experience has taught most of them to revere life, and to respect time. They told us something of the first, and granted us a precious proportion of the second. Without both, this book could not have been written.

Max S. Aber

Otto Bergmann

Rosemarie Bergmann

Hildie Bockow (formerly

Reading)

Meta Bonn

Richard Dresel

Ruth Dresel

Werner Feig

Alice Feilchenfeld

Hans Fisher

Herbert Glass

Herta Glass

Rita Goldstein

Frank Gotthelf

Herman Gronowetter

Lilly Kamin (formerly Joseph)

Carl Lenneberg

George Lenneberg

Gisela Lenneberg

Liesl Loeb (nee Joseph)

Fritz Loewe

Gertrud Mendels (nee

Scheuer)

Pessla Messinger

Frank Metis

George Moss

Thea Moss

Renatta Rippe (nee Aber)

Babette Spanier

Marianne Vargish

(nee Bardeleben)

Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send those, the homeless, tempest-tost to me.

I lift my lamp beside the golden door.

INSCRIPTION BY EMMA LAZARUS

Statue of Liberty, New York Harbor

Yet there comes a time for forgetting,

for who could live and not forget?

Now and then, however, there must also

be one who remembers.

ALBRECHT GOES,

Das Brandopfer

Prologue

On January 30, 1933, Franklin Delano Roosevelt celebrated his fifty-first birthday; in little more than a month he would be president of the United States.

That same day, Adolf Hitler became chancellor of Germany; in a little less than two months, the Reichstag would make him absolute master of his country.

On taking office, the two men faced similar problems, but they chose opposite paths to a solution. Their policies would force them inexorably onto a collision course.

In Germany, the Fuehrer took over a country suffering from self-doubt and in the grip of an economic collapse so serious it seemed insoluble. His solution was to make the Jews scapegoat for all the nations ills. Get rid of them, he maintained, and the patient would recover. Hitler never wavered from this prescription, never concealed it, and by May 1939, thousands had fled, thousands were in hiding, thousands in concentration camps. Though the gas ovens were not yet in operation, many people died daily of malnutrition and maltreatment, and what was happening in Dachau and Buchenwald was already known to the governments of the major powers.

In America, in 1933, Roosevelt had also been confronted by a critical situation. The worst economic crisis in history left banking in chaos: there were some twelve million unemployed; the nation was suffering from an acute loss of self-confidence.

In 1935, Americas isolationism was strengthened with the passing of the Neutrality Act: the United States was not yet willing to take sides.

The Jews in Germanythere were some 500,000 of them when Hitler took powerwere of two minds. Some viewed Hitler as a temporary aberration and waited, alas in vain, for things to change. Other Jews sought to escape. They illegally crossed the borders of Switzerland, Holland, Belgium, and France; they sometimes intentionally broke laws in order to be put into prison, a safer course than being returned to Germany. A small percentage made it to America or England. But for most of those trapped in the German concentration camps, or those about to be put to death, escape could come only if they could convince the Nazis that they could book passage on a ship that would take them away from the Fatherland. There were few ships available, and precious few countries willing to accept them as passengers.

By 1939, Britain, faced with an Arab revolt in the Middle East, was about to drastically curtail the number of immigrants it would allow into Palestine. At home, there were 25,000 refugees. Britain may have been more charitable than many other nations, but His Majestys Government was preparing for all-out war, and there was no great enthusiasm for accepting more refugees from the country Britain was about to fight.