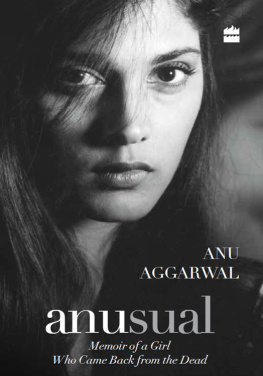

I nearly died that night. The doctors at Breach Candy Hospital in Mumbai still think its a miracle I am alive. Alive to tell you about the love I discovered through a ruptured body, a brain bleed, and several incisions of needles and sutures made with surgical thread tied tight.

Change. Resurrection. Revival. Inner transformation. AnuAnew. AnewAnu. AA.

The story of a girl who was broken into a million pieces but is alive to tell the tale of how, like in a jigsaw puzzle, she brought the separated parts together back again. Realignment. Life 2.

Was it facing mobs of fans, each wanting just a piece of me? And flying high lifted into the arms of a few strapping bodyguards, light as a feather?

Or was it being massacred by glass and metal as a speeding car, in unseasonal heavy rain, made three 360-degree James-Bond kind of turns before crashing on the muddy sands of the Mumbai sea, caving in like a deflated balloon, with me locked in the car?

Or was it getting romantically and spiritually hypnotized by a superyogi, a Paramhamsa, by geometrical images, incandescent light, sound vibrationsand be led to have sex in the forbidden zone?

Love is all there is.

Spring, 1987. On a late sunny afternoon, Rick, the jazz drummer, felt his heart pulsate to a new beat. With breathless excitement he looked at herthe girl from another town with an enigmatic air about her. Her wide shoulders defied the old-fashioned Victorian idea equating a womans beauty with sloping slim shoulders.

On a delicate but assertive tender neckline stood a face with cleverly blended sharp features, a clear jawline with raised cheekbones. Her tender skin texture shone auburn in contrast to the Fair is lovely ideology of India.

Dressed in a multilayered Rajasthani ghaghra with a fine-textured, white, full-sleeved t-shirt, she wore heavy silver trinkets that made their own percussion. On the patio in Carter Road, Bombay, he sat and wondered:

Is she a gypsy, a Sufi, a wanderer? Who is that girl?

Tall, she carried her curvaceous body straight as a pine. Her laser-straight hair with the sheen of the finest pashmina silk swung around, caressing her erect sinuous back. Her laughter was deep-throttle, a bit boyish. A siren song of freedom. She came across as uninhibited.

I dig you, Anu, was a thought he did not put into words; it was a new association.

In a conversation under the coconut tree on the terrace he found out she was not opinionated. She seemed open to joining a party rather than be a party-pooper. Thats cool, Rick would say.

She talked through her deer eyes and spoke little, an attitude that contradicted her bold, forthright gait. He had never seen a prima ballerina with that kind of intensity before. But what struck him most was the rare confidence of the young girl. And the song of Steely Dan, Hey nineteen! Now we can live together, started to play in his musical mind.

Goldmist, the colonial house of his friend Aaditya, acquired a brand new, crazy, magical appeal. Butterflies fluttered in the gold-orange light of the twilight zone. Two lost love birds tweeted in perfect harmony.

Frangipani love. Hibiscus love.

It was a friends wedding that had brought Aaditya to Delhi. The morning after the wedding he was in University of Delhi to meet his friend Gauri. Her corporate father had recently got transferred from Bombay. Dressed in blue jeans, he walked slightly self-consciously in heavy boots. The leather slingbag on his shoulder was a darker shade of his gelled walnut-brown hair.

Love the way you do fieldwork, the way you question teachersI am your fan, Anu, Gauri, a first-year student, my junior in School of Social Work, would admiringly say.

I want to stand first like you did last year.

Squinting in the north Indian hot sun, Gauri was energetic as she rushed to me, presenting him proudly: Anu! This is Aaditya, my friend from Bombay.

Gauris passion for life was unmatched. Trained in Carnatic-style Hindustani classical music, she was also an amazing cook of dosas, but had bad luck with men.

That day, as I stood on the footpath outside the School of Social Work, waiting for a bus to take me home, the bus never came.

Aaditya turned out to be a male of delectable honesty; he had an emotional expressiveness, and a non-macho feelI knew I was going to spend more time with him. A music lover, Aaditya had just got into photography. With the utmost care he showed me black-and-white pictures he had shot of the Bombay jazz band Concoction, where Rick was a drummer.

The pictures came to life on my first evening in Bombay, in Aadityas colonial house. Rick was in the same white plaid pants with black stripes as in the picture, perhaps his favourite, but the heavy muscular tone was visible now.

I had finally accepted Aadityas invite. I was on a ten-day holiday before joining a German NGO to work for womens empowerment; they were to start a new programme in Delhi. They had been suitably impressed with my assistance to a Pakistani NGO to better the lives of Muslim women in Jama Masjid and had offered me a job. To furbish my social assistance skills, I volunteered to design a programme for the repatriation of Afghan refugees with the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR). This made me one of the privileged students in the School of Social Work to have been offered a job even before I (the highest-score holder in fieldwork, first year) had got my masters degree. I was thrilled, especially since the German NGO offered higher wages than what even the UN did.

Aadityas artistically pictorial bedroom, next to a blue glass window open to a turbulent sea, contained all I possessed in Bombay. My army green bag that lay on the maroon tiles of the floor had three cotton changes, a book of poems by Pablo Neruda with a couple of dry roses as markers, a couple of silver trinkets, a personal diary, home-made sesame oil, black kohl that Ma had made from burnt almonds, watercolours and art sheets made of vegetable fibre, and the 800 rupees left over from the government scholarship I had received when I graduated (the rest had been used to buy an Indian Airlines ticket for Delhi-Bombay, and a train ticket back to Delhi).

It was a magical evening. On Aadityas cobble-stoned terrace thrived rare plants, leaves and flowers, the abundance owed to his artist father who watered them fondly each morning. His caring was not a trait restricted only to plants, I would find later, when I got to know his sensitive nature better.

The Bombay sun caught my eye when it descended to the hallucinogenic edge of the sea. The colour in the troposphere moved rapidly from a vague gold to pure orange, and I heard a declaration:

Come live here.

And suddenly, a silver lining emerged from the sky and lined the rays of the setting sun in a mesmerizing hue.

Since Basu Da, Aadityas father, was a film veteran, he received complimentary tickets, and we went to a Satyajit Ray film festival. Aaditya and his girlfriend Sanjana took dutiful turns to show me around, introducing me to their artist friendspainters, writers, musicians, dancers. Bombay was waking up the artist in me. It seemed like a lifetime since I had acted in a play, and theatre was a forgotten word. Though a trained Kathak dancer since I was seven, I did not remember the last time I had tied