BY THE SAME AUTHOR

Eve Arnold: Magnum Legacy

Ghosts by Daylight: A Memoir of War and Love

The Place at the End of the World: Essays from the Edge

Madness Visible: A Memoir of War

The Quick and the Dead: Under Siege in Sarajevo

Against the Stranger: Lives in Occupied Territory

THE MORNING THEY CAME FOR US

Dispatches from Syria

Janine di Giovanni

LIVERIGHT PUBLISHING CORPORATION

A Division of W. W. Norton & Company

Independent Publishers Since 1923

New York London

Copyright 2016 by Janine di Giovanni

First American Edition 2016

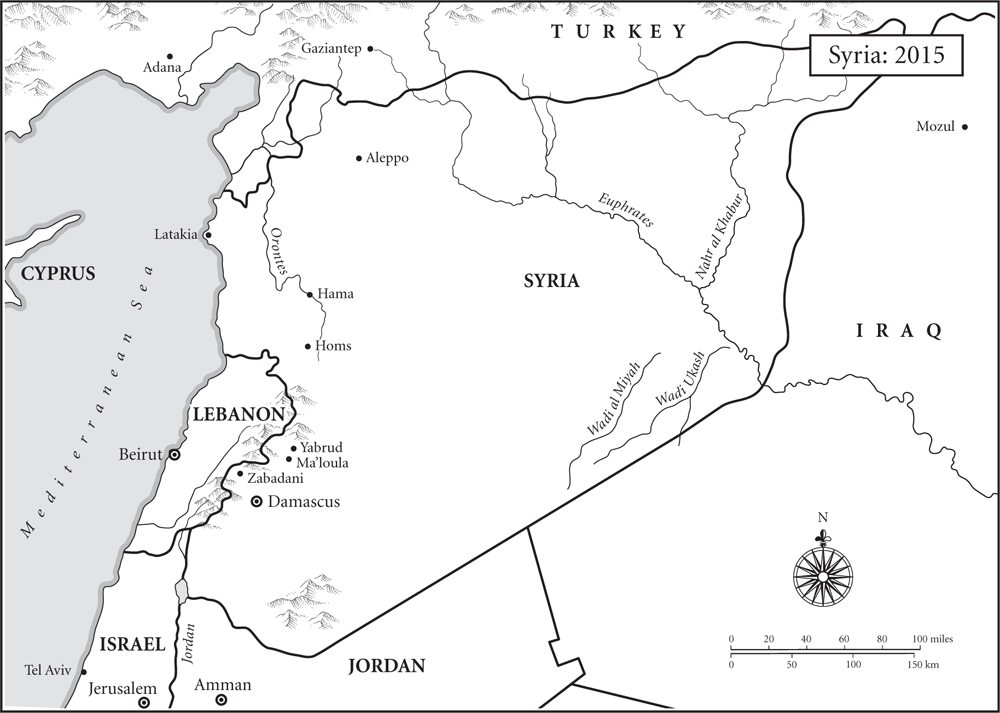

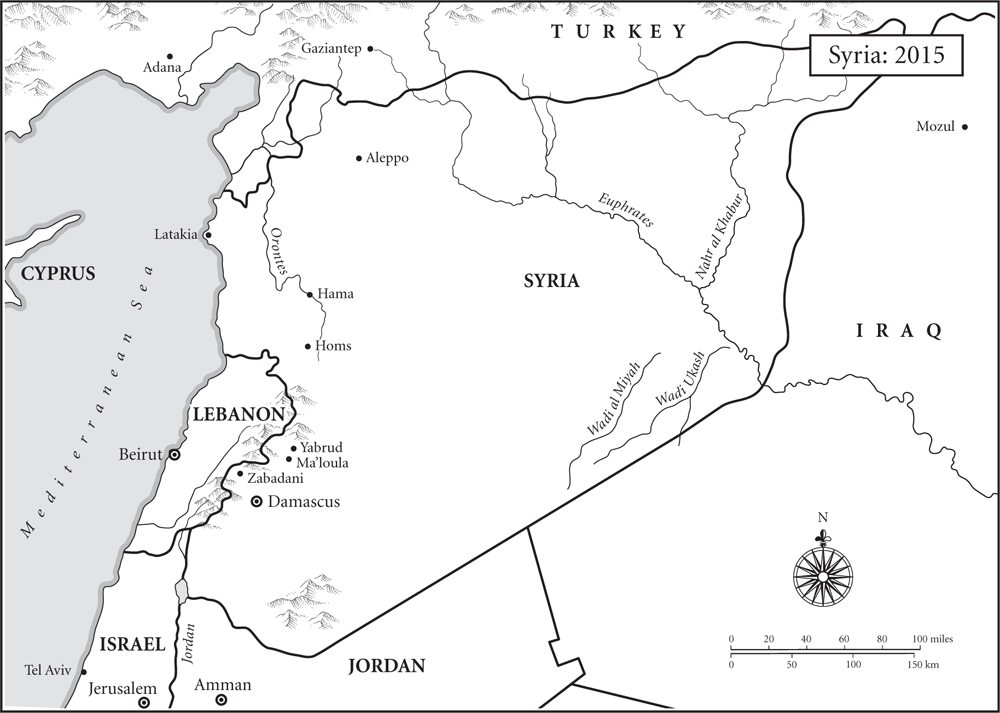

Maps by John Gilkes

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, Liveright Publishing Corporation, a division of W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact W. W. Norton Special Sales at specialsales@wwnorton.com or 800-233-4830

Production manager: Anna Oler

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Names: Di Giovanni, Janine, 1961- author.

Title: The morning they came for us : dispatches from Syria / Janine di Giovanni.

Description: New York : Liveright Publishing Corporation, [2016] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016007537 | ISBN 9780871407139 (hardcover)

Subjects: LCSH: SyriaHistoryCivil War, 2011Personal narratives, Syrian.

Classification: LCC DS98.6 .D54 2016 | DDC 956.9104/2dc23 LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2016007537

ISBN 978-0-87140-383-4 (e-book)

Liveright Publishing Corporation

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd.

Castle House, 75/76 Wells Street, London W1T 3QT

In memory of my beloved brother, Joseph, who died suddenly on 11 August 2015

Only the dead know the end of war.

Plato

In such a world of conflict, a world of victims and executioners, it is the job of thinking people... not to be on the side of the executioners.

Howard Zinn, A Peoples History of the United States

Wars have no memory, and nobody has the courage to understand them until there are no voices left to tell what happened, until the moment comes when we no longer recognize them and they return, with another face and another name, to devour what they left behind.

Carlos Ruiz Zafn, The Shadow of the Wind

Contents

It was the winter of 2011, and I was in Belgrade. The war that had destroyed Yugoslavia had been over for many years, but I was working on a project tracing war criminals. It was an intractable task, but the potent emotion I felt towards the Balkan wars and their aftermath was not rational.

It was a terrible fever not unlike malaria, recurring in your bloodstream for ever once you got it that had gripped me since I had reported from Bosnia in the early 1990s. The men who had caused such evil and such harm, who had burnt villages and bombed schools and hospitals, who had mutilated children and raped women en masse, were still living in villages, going fishing at weekends and having picnics with their grandchildren. It made me feel physically ill thinking about them living unreservedly while their victims were dead; and I would trail the events that led to the downfall of that sorrowful country. In Sarajevo one year, I spent days, which turned into weeks, with the man who ran the morgue during the war. He had not only arranged the bodies and prepared them for burial but he also diligently kept notebooks with every name, every detail of their time and their cause of death (bullets, shrapnel, explosion). He called it The Book of the Dead . One morning, he arrived at the morgue and found his only son, a young front-line soldier, laid out on the slab.

He survived and grew old, and when I found him two decades after the war ended, we went through the books carefully. But his partner at the morgue, a less robust man, had killed himself years before.

I wanted my fever to break, but it never did. Throughout the new millennium, criminals from the Balkan wars, rapists and murderers, went unpunished. I talked to women who had been kept in camps and violated sometimes a dozen times a day; women who were forced to carry their rapists children. Yet post-war, owing to the division of the country, and the fact that no one really knew who their neighbours were any more, these women had to face their rapists daily, passing them in the local shops or on the street, at the schools where they took their children. It was the victims, not the perpetrators, who dropped their eyes in shame when they passed one another.

But some of them met their fate. Radovan Karadzic, the psychiatrist, football fanatic, poet and leader of the Bosnian Serbs, who led the puppet regime for Slobodan Milosevic, the former president of Serbia, had been caught while riding on a bus in 2008. He had been in disguise, and had been in hiding since the war ended in 1995, living under a false name and posing as a New Age healer. Karadzic is, at this time of writing, being tried for alleged war crimes but no verdict has been reached.

Slobodan Milosevic, the leader of Serbia throughout these wars, had been carted off to The Hague in his bedroom slippers by helicopter in 2001. The day it happened I was also in Belgrade, but I drove all night to get to Sarajevo, the city he had hated and almost destroyed, to witness the reaction of the people. I expected to find jubilation that Milosevic was getting his just deserts, but instead I found weariness. My friends former soldiers, lawyers, students, doctors, mothers, teachers were too tired to celebrate, to think that this meant something in terms of retribution. Everyone just wanted to forget about the war that had devoured them alive.

I felt the greatest revenge was that the man who had caused such pain to his own people would sit in a jail cell in The Hague for the rest of his life, but Milosevic did not, in fact, face justice. He was found dead in his cell in 2006, under mysterious circumstances. Some said suicide; some said his devoted followers had slipped him a pill which made his heart quicken and burst; some say he died of heartbreak. The fact was, this wicked man had died before justice had been served.

Still at large on that winter afternoon in January 2011, while I sat in a freezing caf in New Belgrade talking to men who had once fought alongside him, was Ratko Mladic, the general who had led his men on a rampage and who had headed the assault on Srebrenica. He was sleeping soundly in some village in Serbia, protected by his followers, while the families of the 8,000 men and boys killed in Srebrenica had to live with their ghosts, their memories of their loved ones fading more and more into the distance every day. At the moment, he stands accused of war crimes no verdict has been reached as the trial has not yet concluded.

I was not a criminal investigator, and I knew that I would not be the one to march up to Mladic and put the handcuffs on him before he was arrested, but in some ways, I had much more freedom than police. I could sit in cafs where Mladics followers gathered to drink their morning tea, and ask where he had last been seen. I could sit by the grave of his daughter, who had tragically killed herself during the war, and ask the woman who kept the graves when she had last seen him; what his mood was; how he appeared physically. I could try to put myself in his mindset. In building up a portrait of the tormented Mladic, I wanted also to make him immortal: as immortal as those it is claimed he had murdered (though he denies murder).

Next page