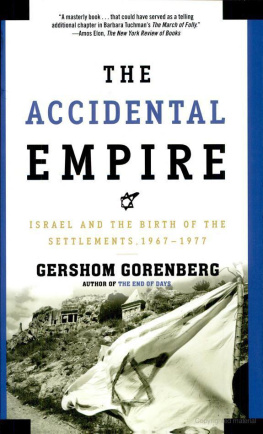

ALSO BY GERSHOM GORENBERG

COAUTHOR

SHALOM, FRIEND

The Life and Legacy of Yitzhak Rabin

EDITOR

SEVENTY FACETS

A Commentary on the Torah from the Pages of the Jerusalem Report

THE FREE PRESS

A Division of Simon & Schuster Inc.

1230 Avenue of the Americas New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

Visit us on the World Wide Web: http://www.SimonSays.com

Copyright 2000 by Gershom Gorenberg

All rights reserved, including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form.

THE FREE PRESS and colophon are trademarks of Simon & Schuster Inc.

ISBN 0-7432-1621-0

eISBN: 978-0-743-21621-0

In Judis memory

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

THE BEGINNING IS NIGH

THE BELL TOLLED at midmorning, summoning the faithful to their church. They trooped down the hillside silently; theyd abjured unnecessary speech, along with sex and liquor. Some stopped to pour out food they wouldnt need, covering the path with flour.

The members of the Movement for the Restoration of the Ten Commandments, a shoot sprung from the trunk of Catholicism, had expected the world to end in 1992, in 1995, and on the last day of 1999. Despite their prophecies failures, theyd continued recruiting new members. Now, on March 17, 2000, they knew the Virgin Mary was about to come to take them to heaven. Theyd celebrated, slaughtering three bulls, at their compound at Kanungu in the fertile hills of south Uganda; theyd burned clothes and money, vestiges of earthly life. Inside the building, waiting, they sang and chanted. Someone nailed shut the doors and windows.

The End came in a flash of gasoline-fed flames.

Afterward, local police guessed that 530 people died in the fire. The dead were hard to count, since ashes were all that was left of many bodies. Within days, police found some four hundred more corpses buried in pits at Kanungu and other sect compounds. The signs were that theyd been stabbed, strangled, or poisoned in the weeks before the fire, though neighbors had heard nothing, no cries of resistance.

Ugandan officials described the case as mass murder, rather than mass suicide. They posited that the sects leaders had escaped, taking the wealth of the members; warrants were issued for their arrest. An AP report referred to Credonia Mwerinde, who founded the movement after seeing visions of the Virgin, as a huckster and charlatan. It fit a common description of cults that predict the Endcon-man leader, duped followers. Perhaps that was less frightening than another possibility: that hoping for historys end and the kingdom of God, sane people had killed or had willingly died, based on beliefs an inch or three away from those of established religions. But in the first days after the fire, it was impossible to prove either explanation of the catastrophe. The witnesses had left this life.

One thing should be clear: A certain sigh of relief elsewhere in the world at the start of 2000 had been altogether premature. In the months before the turn of the millennium, media reports and security agency assessments warned that religious groups might commit violence to help the End begin. At the same time, newspapers carried updates on concerns that the Y2K bug would stop computers at midnight, December 31, 1999. That whiff of techno-apocalypse helped merge the two concerns. So did the use of millennium to refer both to the Christian belief in Gods kingdom on earth and to the biggest New Years party ever. It was easy to get the impression that anyone predicting the End was expecting it that midnight, and that if anyone acted on the belief, thats when hed do so. But the magic minute passed, the computers didnt even hiccup, and no cultists killed themselves. Ergo, the religious concerns were misplaced, just like the technological ones.

Just two and a half months later, fire swept through a Ugandan church. Reading the reports in Jerusalem, I was sickened, but not surprised.

As a journalist and an associate of the Center for Millennial Studies, I study people who believe we are living in historys final days. Popular depictions of such people are often simplistic, drawing too great a separation between doomsday cults and mainstream society. The fact is that millions of quite rational men and women, belonging to established religious movements around the globe, look forward to historys conclusion, to be followed by the establishment of a perfected era. They draw support from ideas deeply embedded in Western religion and culture. You dont need to go to central Africa to find them; they live in American suburbs; they work in insurance offices and high-tech startups. Some are influential leaders of Americas Christian right.

Likewise, the fear that any outburst of violence would occur on January 1 was mistaken: It fed exaggerated concerns about that day, and overlooked more serious risks afterward. In fact, the Uganda tragedy fit a pattern familiar to researchers: The deaths came as a delayed reaction, after reality repeatedly defied prophecy. Worse, there was no reason to assume that the Ugandan case would be the last outburst of violence linked to expectations of the End. The turn of the millennium marked not the end of the danger, but the beginning of a dangerous time.

Living where I do, I take that danger seriously. If theres any place in the world where belief in the End is a powerful force in reallife events, its the Holy Land. The territory today shared and contested by Jews and Palestinians is the stage of myth in Christianity, Judaism, and even Islam. When a great drama is played out here, the temptation to match events with the script of the Last Days can be irresistible. For a century just such a drama has been acted out, compelling the worlds attentionand firing expectations in all three religions among those who hope for the End.

The impact of such belief on a complex national and religious struggle has received too little attention. It underlies the apocalyptic foreign policy promoted by many on the American religious right: support for Israel based on certainty that the Jewish state plays a crucial role in a fundamentalist Christian script for the End. In Israel, belief in final redemption has driven the most dedicated opponents of peace agreements. Among Muslims, expectation of the final Hour helps feed exaggerated fears about Israels actions in Jerusalem. Belief in the approaching End has influenced crucial events in the Arab-Israeli conflict. Time and again, it has been the rationale behind apparently irrational bloodshed, and undermined efforts at peacemaking. In the worst case, desire for historys finale has the potential to spark all-out war in the Middle East.

And heres the paradox: The worlds resolute refusal to end doesnt mute expectations; it turns them up. In the years to come, therefore, hope for the End will continue to exert political influenceand its potential to set off violence will only increase. That hope is more than a fantasy; it has the power to affect our world. The purpose of this book is to show why.

I CAME TO JERUSALEM from California in 1977. I was a year out of college. I came to study Judaism in the Holy City for a year, but I had a one-way ticket. I had nothing written down for the future. I fell in love with the place and, surprising myself, I stayed.