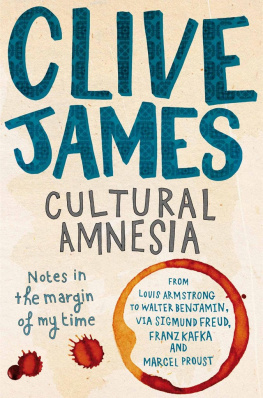

To Christopher Hitchens in affectionate disagreement

Mankind is conservative. When this tendency weakens, however, revolutions devote themselves to its renewal.

Ernesto Sabato, Uno y el universo

The generations work within each other in the most amazing way, and it doesnt need the Kingdom of Death to bring people of profoundly different times together in speech.

Golo Mann, Friedrich von Gentz

Just as to the eyes of the emigrant who goes home after a long exile the familiar appears stripped clean, so the assimilated man possesses a particular acuity of gaze: the cultural manifestations with which he lacks an intimacy become the frozen material of his absorption, and thus reveal their structures all the more clearly.

Jrgen Habermas, Philosophische-Politische Profile

Introduction

A man either has a picture of the world, or he lives in a world of pictures. In the first case, he has only to report the facts, and his report will have style. In the second case, he may strive for a style all he likes, but he will never have one.

Anton Kuh, Luftlinien

Finally, it is a writers way of putting things that gives unity to his work. There is no other unity that the fugitive pieces in this book can claim, but I dont need telling that it is a large claim to make. It is like saying that fragments can add up to an edifice. None of the pieces here collected, however, felt like a fragment at the time. They all felt like something to which I was giving everything I had, even when the subject seemed trivial. And some of the subjects, alas, didnt seem trivial at all.

They never have. Six decades after I was born into its years of triumph, the Nazi era is still here, still at the centre of intellectual discussion, still demanding, insatiably, to be dealt with. The same applies to the Soviet Union, which is gone but not forgotten a lot less forgotten, in fact, than it was when it was still in business. In the year of my birth, Stalins terror was at its frenzied height: in the year I turn sixty, scholars are still trying to find out exactly what went on. The scholars who finally figure it all out will almost certainly have come into the world long after those particular horrors happened. My only claim to expertise is that I was there, when all those innocent people were being obliterated. It was clever of me to be less than four feet tall and to have chosen Australia as my birthplace, a good way away from the nearest mass graves, but I still got a solid dose of the insecurity that radiates from historical disaster and works its most arresting mental distortions on minds of a tender age. (Nor, indeed, were the nearest mass graves all that far away: while I was running in baggy shorts around the back garden, blasting the sugar-ants with my wooden machine-gun, the Imperial Japanese Army was still busy reminding the Asian and Pacific countries it had promised to liberate from colonialism that they had been wrong to suppose there could be nothing worse than European arrogance.) When you grow up in an epoch seemingly dedicated to extermination, it influences your world view for life. Opinions can change they are on the surface of the mind but a world view is part of the soul, as fundamental as your sense of what is fair or funny. When we shy from a man who tells tasteless jokes, it isnt his wit that we dont like, its his Weltanschauung. Hitler, after all, could be quite a card.

Throughout my six collections of non-fiction, it is thus no mystery that there is a consistency of outlook: nobody else would be unable to say the same. The only mystery is why I should have bothered to express it. I could say that for anyone who earns his living by being unrelentingly allegro it is hard to resist the temptation of proving himself penseroso as well: we all like to be thought deep. But there has always been more to it than that, or anyway it has always felt to me as if there has. If I had wanted to be thought deep, I would have spent the last thirty years proposing something a lot less scrutable than the elementary proposition that democracy is even more important for what it prevents than for what it provides. Some quite complicated issues grow out of that proposition the most troublesome being that a free nation is bound to provide opportunities for incitement to the very kind of suffocating orthodoxies whose hegemony it exists to prevent but there is nothing complicated about the proposition itself, beyond the consideration that historic circumstances drilled it into my head almost before I could spell the words in which it is written. The best justification for plugging away at the self-evident, it seems to me, arises from the lurking fear that for too many people who should know better it doesnt seem to be self-evident at all. My first book of essays, The Metropolitan Critic, was assembled in 1974 in the immediate aftermath of the counterculture, which some of its illuminati fancied as the Cultural Revolution of the West. (Their notions of what the Cultural Revolution of the East had really been like, it must be said in mitigation, were of the haziest.) Many of the pieces in the book had been written when the idea was still in vogue that youthful values represented some kind of political vision all by themselves. Still feeling quite youthful myself at the time, I thought there was something to it, and said so: there was a new generosity in the air, and American foreign policy, with the disaster in Vietnam as its stellar achievement, did need opposing the patent decency of some of its American opponents was sufficient evidence of that.

But here already the difference between mere opinions and a world view showed up with awkward clarity. The undoubted fact that democracy was currently making a murderous fool of itself couldnt make me forget that totalitarianism was still the enduring and implacable antagonist. I had opinions about what a democratic state should do in the circumstances pull out of Vietnam, decommission the CIA, put Henry Kissinger on trial for sedition, stop subsidizing the kind of dictators who exported their own economies to Switzerland but it was part of my world view that a totalitarian state was unjustifiable in any circumstances. The boat people hadnt yet set sail, but I was already with them in spirit. It bothered me that there were so many of our bright young people eager to buy the whole radical package, up to and including the potentially lethal notion that if the representative political structure could be reduced to a state of nature, paradise would ensue. Weve got to get ourselves back to the garden. The universities, in particular, were stiff with young enthusiasts who plainly had no idea of what could be lying in wait for them at the bottom of the garden, especially at night. Even worse, some of the loudest enthusiasts were on the faculty, actually teaching that the tenure they themselves had safely attained was not worth having, that the modern democratic state was the repressive mechanism of late Capitalism, that but there was no end to it.

There never would be an end to it. Such was the realization that completed my battle with the eggshell. To find ourselves, we all have to fight our way out of isolation, because it is only in the community outside that individuality is to be had. The role of the freelance man of letters (the personage on whom I so blithely conferred the title of Metropolitan Critic) is to accept and to act on the acceptance that he is engaged in a perpetual discussion, an interminable exchange of views in which he cannot, and should not, prevail. If he could prevail, and the discussion did terminate, he would have become his enemy, the dogmatist whose only answer to opposition is annihilation a response which, for a mercy, he is usually allowed only to dream of, but which he would put into practice if he could.

Next page