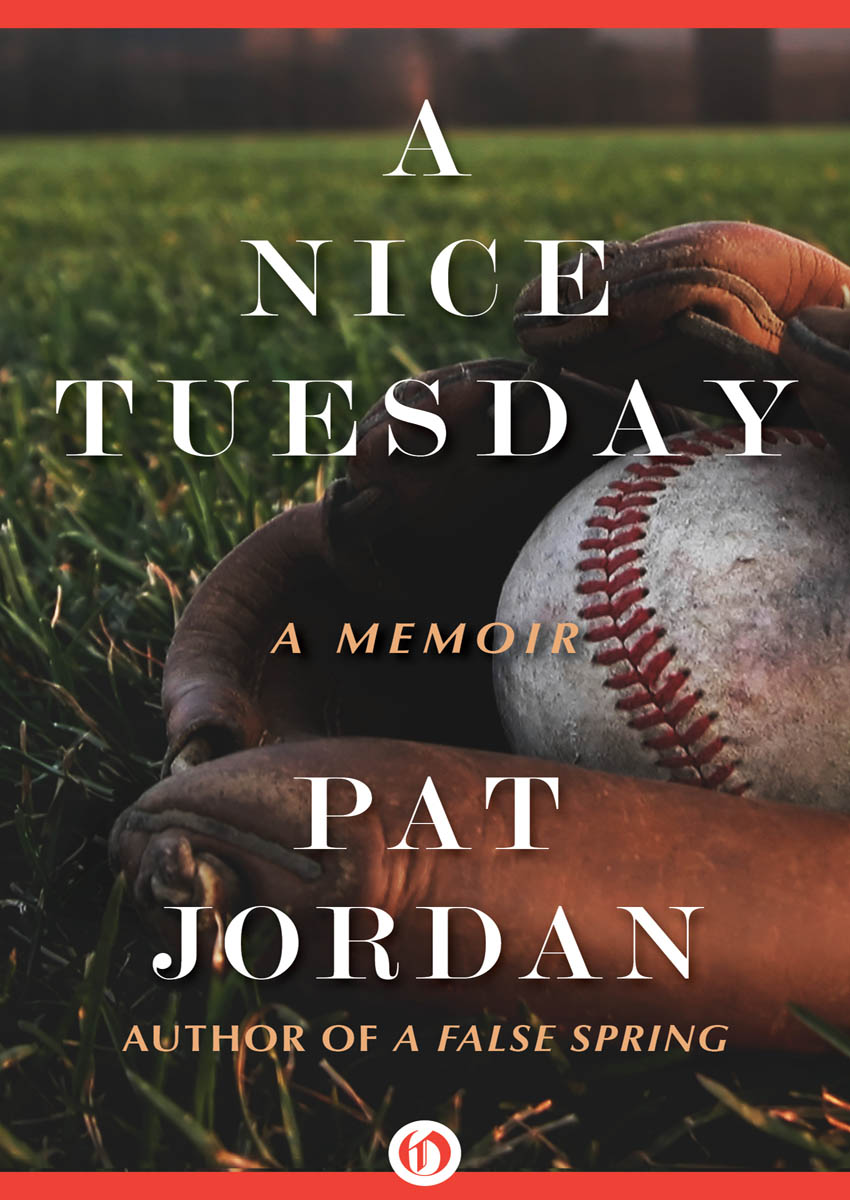

A Nice Tuesday

A Memoir

Pat Jordan

For Hoshi, Kiri, Stella, Nero, Bubba,

Blue, Sweetness, Francis, and the Usual Suspects.

For Brian LaBasco, without whom this book

couldnt have been written.

For my brother and his wife, and my mother and father.

And finally, as always, for Susan,

and her mother, Peg, whom Ive never met

but who is always there for us.

The mind is its own place, and in itself can make a heaven of hell, a hell of heaven.

John Milton, Paradise Lost,

Book 1, lines 2545.

I am such an egotist that if I were to write about a chair I would find some way to write about myself.

paraphrased from a French dilettante

What would I be without baseball? I could think of nothing.

Pat Jordan, A False Spring

He cannot be a gentleman which loveth not a dog.

John Northbrooke, Against Dicing (1577)

O NE

I see myself as I am now, sitting at the head of the dining-room table at my most recent birthday party. My wife and my friends are sitting around me. They are drinking, smoking, laughing, gesturing with their hands, shouting to be heard. I am silent, smiling at my friends. A beautiful girl is sitting on each knee. One is blonde, thirty, with a languid touch. She rests her hand lightly on the nape of my neck and strokes my short hair. The other is a redhead, twenty-seven, with perfectly shaped breasts half exposed beneath her flimsy T-shirt. She is whispering in my ear, her breast pressed against my shoulder. I laugh. The two girls look down at me. They smile, dreamily, at me a rough, good-looking man with curly hair, tall, trim, muscular.

Ronnie stands, weaving unsteadily, and aims a Polaroid camera at me and the two young girls. I put one hand on the naked thigh of the blonde and the other on the firm right breast of the redhead. The girls squeal with mock outrage, but do not push my hands away. My friends hoot at me with derision. Peter rolls his eyes to the ceiling. George and Al grin like elves. Sol smirks in disgust and turns his face from me. Phil throws up his hands, as if pleading. My wife shakes her head in weary resignation.

I smile seductively into the camera. Ronnie snaps our photograph. He hands me the developing snapshot. Its blurry gray, then grows darker as images form before my eyes. Colors appear. The two young girls appear. I appear! An old man! With a white beard! I am wearing a ridiculous-looking aqua-blue Hawaiian shirt dotted with pink flamingoes. I am leering like an old fool, with a cigar clenched between my teeth and two beautiful girls sitting on my knees, smiling at menot dreamily, but with the condescending affection young girls reserve for belovedly lecherous, harmless old men.

I stare at the photograph. Finally it registers. I mutter to myself, Jeez, I look like an old man.

My friends hear me. They shout in unison, You are an old man!

My wife smiles at me, with pity.

The two young girls hug me. The blonde says, But we love you, Patty.

The redhead takes my hand and places it over her breast. There, she says. Feel better?

Its funny how we see ourselves. It bears no relation to how others see us. It doesnt matter how others see us. It matters only how we see ourselves, frozen at those points in time that most truly defined us. It doesnt matter that our self-perception is a delusion. It matters only that to us its real, that in our minds eye we will always be what we were at those points in time that we decided most truly defined us.

I see myself at another birthday party almost fifty years ago. I am helping my mother set the kitchen table for my eighth birthday, in our new house in an old, Waspy, New England town.

Put the Cassatta in the center of the table, she says. She is stirring the spaghetti sauce at the stove.

I slide the big heavy cake off the counter and carry it to the table. It has a plain yellowish frosting on top that tastes of butter and heavy cream. Its sides are coated with slivers of faintly bitter, toasted almonds. The filling is a semisweet custard flecked with bits of bittersweet, dark chocolate. The cake itself is as dense as peasant bread, chewy and moist and soaked with rum.

Ma, why cant I have a cake like my friends? My new friends in the suburbs always have birthday cakes as light as air, with sugary, whipped cream frosting as white as snow, and strawberry preserve filling, and hard, pastel-colored, sugar flowers on top that surround the words Happy Birthday, scripted in hard blue sugar.

Your aunts and uncles like Cassatta, she says. She tastes the sauce from a wooden spoon. She means my Uncle Ken, the judge, and his wife, Josephine. My Uncle Pat, the stockbroker, and his wife, Marie. My Uncle Ben, the draftsman, and his wife, Ada. Aunt Jo and Aunt Marie are my mothers sisters. Uncle Ben is her brother. My father has no relatives. He is an orphan who never knew his parents. His only relatives, he says, are my aunts and uncles, who will be my only guests at my eighth birthday party.

Now get the antipast, says my mother.

I take out the huge round silver tray of antipasto from the refrigerator and lay it next to the cake. It looks like a big flower with its petals of sweet red roasted peppers, sardines, calamari, artichoke hearts, black and green olives, thinly sliced, tightly rolled Genoa salami and prosciutto, chunks of Asiago and Pecorino, and, in the center, the heart of the flower: a round of tuna fish.

The vino, she says.

I get the plain gallon jug of red wine from the floor of the pantry and struggle with it to the table. I put it down with a thunk. My mother turns and glares at me, then goes back to her sauce. I know enough not to ask her why I cant have hot dogs and Coke and colored balloons and my new friends at my birthday party. Balloons are a waste of money, she says. My new friends are a bother, she says. And my aunts and uncles, she says, certainly cant be expected to eat that Irisher food.

She calls my new friends Irishers with a dismissive toss of her hand. But my new friends are not all Irish. They are English and German and Swedish and Jewish and Russian too. But that is all the same to my mother. Theyre white, she says, and expects me to know what that means.

We are the first Italian family to move into this Waspy suburb, and we are certainly the only family here whose breadwinner sleeps all day because he supports his family by gambling all night. Thats the real reason I cant have my new friends to my house. My mother is afraid they will tell their parents my father sleeps all day. Or, worse, that when he finally rises at three oclock he sits at the kitchen table drinking espresso with a lemon peel while he holds up pair after pair of red Lucite dice to the light, turns them over and over until hes satisfied, and then puts each pair in a meticulously numbered box.

If they ever ask, my mother tells me, say your father works the night shift at the Brass factory.

So I go to my new friends houses instead. My mother doesnt mind. Good, she says. Youll be out of my hair.

I love going to my new friends houses. Its a strange, new, exotic world for me. My new friends have dogs and cats and little sisters and freckled moms and smiling dads, who never speak loudly, in Italian, or gesture with their hands. Their dads are never too busy to go outside in the street and toss a baseball to them and their friends. Their moms are never too busy to make peanut butter and jelly sandwiches and glasses of milk for them and their friends. Peanut butter and jelly is so exotic to me. For lunch? My lunch is always pizza fritedough fried in olive oil and then sprinkled with confectionary sugar. Or eggs scrambled in olive oil with sweet red peppers and crusty Italian bread. I never knew scrambled eggs were supposed to be yellow until I went to my new friends houses and saw their mothers cook them in butter. My eggs, scrambled in olive oil, were always a dirty brown.