1968 IN AMERICA

1968

IN AMERICA

MUSIC, POLITICS, CHAOS,

COUNTERCULTURE, AND

THE SHAPING

OF A GENERATION

Charles Kaiser

WEIDENFELD & NICOLSON

New York

Copyright 1988 by Charles Kaiser

All rights reserved. No reproduction of this book in whole or in part or in any form may be made without written authorization of the copyright owner.

Published by Weidenfeld & Nicolson, New York

A Division of Wheatland Corporation

841 Broadway

New York, New York 10003-4793

Published in Canada by General Publishing Company, Ltd.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Kaiser, Charles.

1968 in America.

Includes index.

1. United StatesHistory19611969. 2. United StatesSocial conditions19601980. 3. Subculture. 4. United StatesPopular cultureHistory20th century. I. Title.

E846.K291988973.92388-14429

ISBN 978-0-8021-9324-7

Manufactured in the United States of America

Designed by Irving Perkins Associates

First Edition

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Due to limitations of space, permissions and acknowledgments appear on page 291.

For Joe,

For Jerry,

and For My Parents

CONTENTS

PREFACE

W HEN Theodore H. White published The Making of the President, 1960, the book that revolutionized the way Americans write about politics, every member of my family fell in love with it. It was 1961, and I was ten years old. A few months earlier, on January 20, I had shoveled the snow out of our driveway in Bethesda, Maryland, so that my mother could drive me downtown to watch the inaugural parade. As John F. Kennedy passed by hatless in an open car, I shouted out, Good luck, Jack! When the new president turned to look in my direction, a young friend who sat shivering next to me in the reviewing stand was sure our hero had heard me.

That was the closest I ever got to Kennedy. But Teddy White was a good friend of my parents, and I met him for the first time a couple of years later. No one has ever been kinder to kids who hoped to emulate him than Teddy. Unlike so many famous people, he never demanded reverence. He did not expect it, probably because he knew the arrogance of youth would not permit it. He loved young people and he loved politics, and he especially loved young people who loved politics, even when they argued with him, as I often did from the other side of the generation gap.

Teddy gave me every encouragement to become a writer, including the crucial one of his own example. He inscribed my family's copy of The Making of the President, 1968: For Charles, and Hannah and Phil, and all the Kaisers whom I love, but mostly for Charles, who thinks politics may be worth reading and writing about. Through the generosity of his widow, Beatrice, and his children, Heyden and David, I was the first person to be given access to his massive archive after his death, in 1986. Without Teddy's documents it would have been impossible to produce this volume.

I WROTE this book to try to understand the impact of a single year when so many grew up so quickly. For a surprisingly large number of Americans, I think 1968 marked the end of hope. Twenty years later, it may now be possible to start unraveling the mystery of how its traumas and its culture changed us. If we can appreciate the triumphs, perhaps we can finally get over the tragedies.

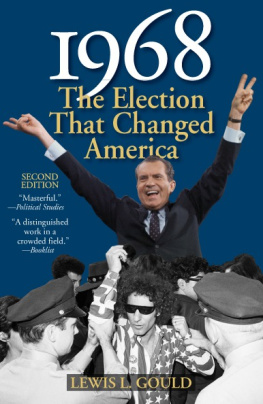

This account is primarily about the people of all ages who believed that fundamental change was possible and necessary in America in 1968, and about the culture that shaped that conviction. It is a book about the power of idealism, the power of music, the power of the bullet, and the power of the press. It is also the story of what it felt like to grow up in a time when every established norm seemed to be under siege. Drugs such as marijuana, once confined to the ghetto (and the jazz musicians who discovered them there), were suddenly available on almost every college corridor. Broadway theatergoers accustomed to fully clothed actors were getting their first dose of full-frontal nudity in a tribal-love-rock-musical called Hair. Off-Broadway, straight and not-so-straight audiences were absorbed by an explicit (though still utterly self-loathing) depiction of gay life in The Boys in the Band. A computer named Hal in a movie called 2001: A Space Odyssey replicated every human personality trait, and some viewers even speculated about Hal's sexuality. Newsweek ran a cover story asking whether men should wear jewelry, while women's skirts inched higher above the knee than either man or woman had imagined possible. On daytime television, Tommy Hughes was toking up in As the World Turns and Tom Horton was impotent on Days of Our Lives. At the beginning of the year, you could pick up the phone in New York City and Dial-a-Poem by June you could also Dial-a-Demonstration. That fall, for the first time ever, Columbia men gained the right to entertain women in their dormitory rooms twenty-four hours a day.

Blacks were beautifuland growing Afros and raising their fists in a defiant Black Power salute at the Olympics to prove it. Violence was everywhere, especially during February in Vietnam, where the Tet offensive drenched that country in blood, and in American streets two months later, when 65,000 troops were needed to quell riots in 130 cities after Martin Luther King, Jr.s killing. Go home and get a gun was Stokely

I have tried to make reading the book as much as possible like living through the year. But one of the qualities that made 1968 so exhilaratingthe virtue we made of nonconformityalso makes it especially treacherous to generalize about. There were so many separate movements for change, so many musical styles, and so many methods of mind alteration that it was unusually easy, even for two people the same age growing up in the same small town, to have opposite interestsand fierce disagreements about what it was that really mattered. The passage of time has done little to diminish the intensity of these controversies.

So I cannot tell the truth about the Beatles, Bob Dylan, Walter Cronkite, Gene McCarthy, Bobby Kennedy, or Martin Luther King. The same problem would arise in dissecting the social and political movements of any year; in this case it is particularly acute. The most I can do is to write what I think is important about some of the things we all experienced, because we all experienced them so differently. I only hope that even those who are infuriated by my very personal judgments will concede that the vehemence with which they are expressed is in keeping with the spirit of the era I love.

Would you believe in a love at first sight?

Yes, I'm certain that it happens all the time.

J OHN L ENNON AND P AUL M C C ARTNEY

INTRODUCTION

Bringing It All Back Home

T HIS is the story of what happened to America in 1968, the most turbulent twelve months of the postwar period and one of the most disturbing intervals we have lived through since the Civil War. In this century only the Depression, Pearl Harbor, and the Holocaust have punctured the national psyche as deeply as the dramas of this single year. Nineteen sixty-eight was the pivotal year of the sixties: the moment when all of a nation's impulses toward violence, idealism, diversity, and disorder peaked to produce the greatest possible hopeand the worst imaginable despair. For many of us who came of age in that remarkable era, it has been twenty years since we have lived with such intensity. That is one of the main reasons why the sixties retain their extraordinary power over everyone old enough to remember them.

Next page