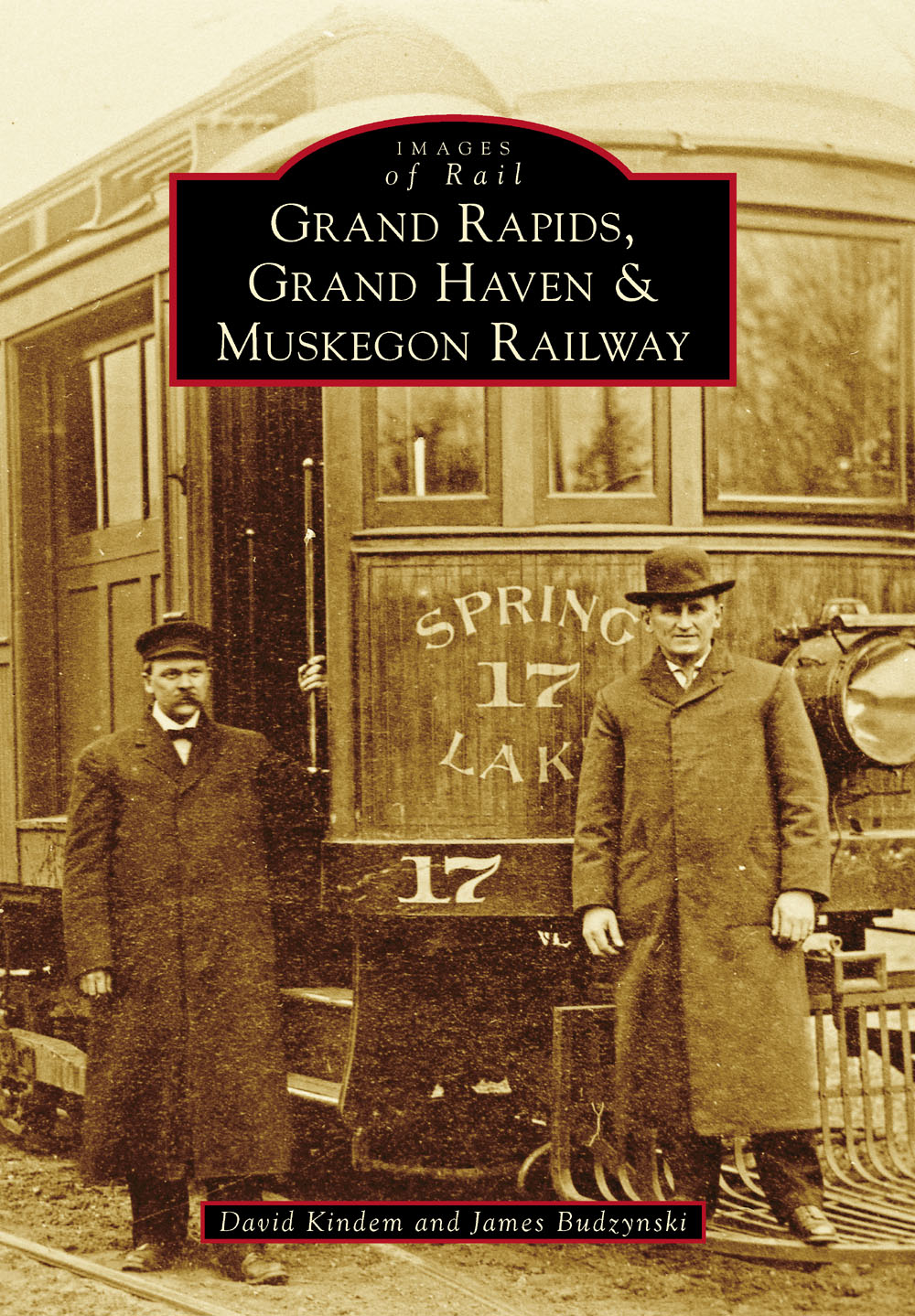

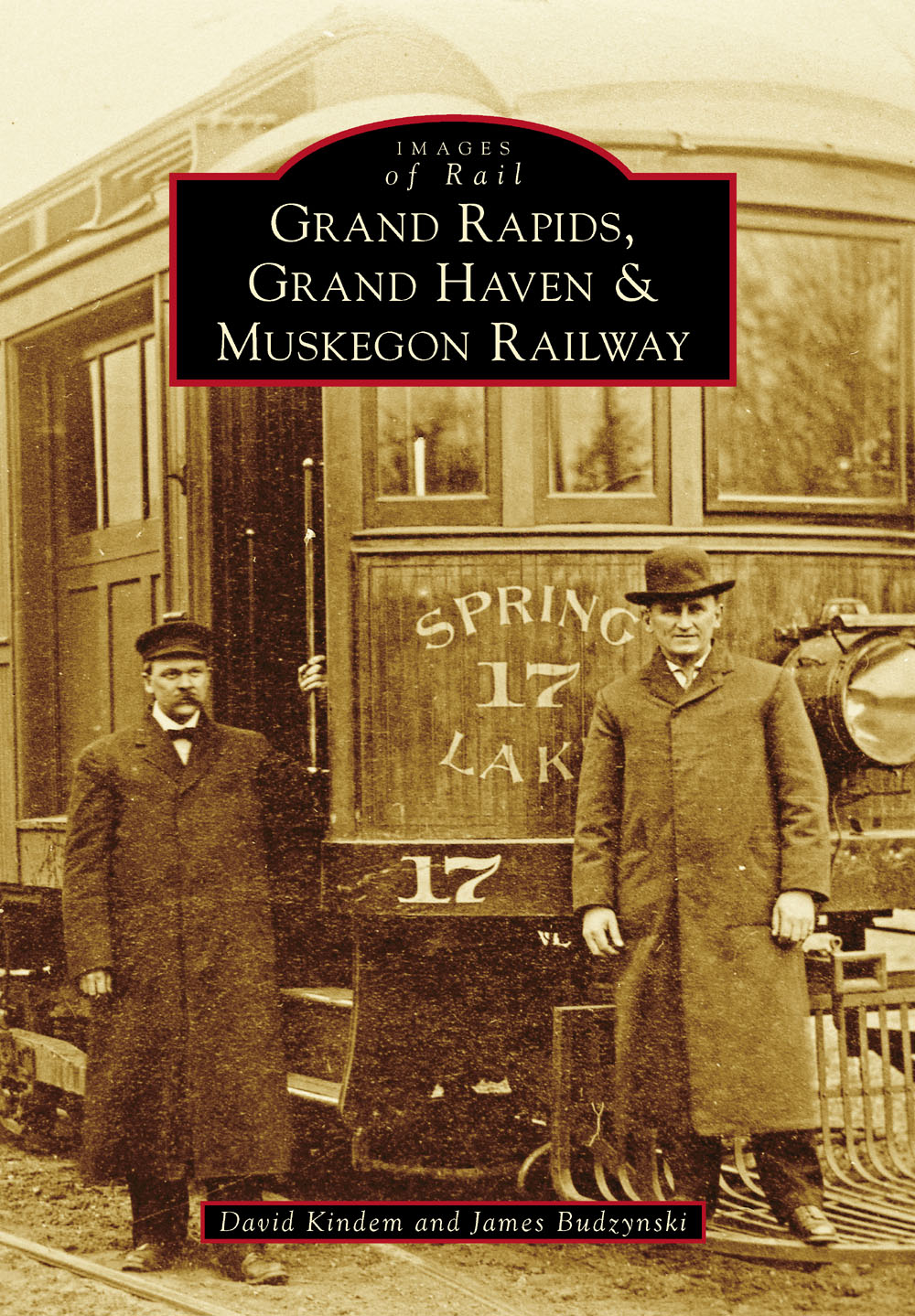

IMAGES

of Rail

GRAND RAPIDS,

GRAND HAVEN &

MUSKEGON RAILWAY

ON THE COVER: Grand Rapids, Grand Haven & Muskegon Railway (GRGH&M) Car No. 17 stands near the companys carbarn in Fruitport, Michigan. The combination passenger-baggage car was built by the Jackson and Sharp Company. The combination cars had a large baggage compartment, which suited them for connections with the cross-lake steamships that brought passengers between west Michigan and Chicago or Milwaukee. The cross-lake boat traffic was an important source of income to the GRGH&M. (Courtesy of the Coopersville Area Historical Society Museum.)

IMAGES

of Rail

GRAND RAPIDS,

GRAND HAVEN &

MUSKEGON RAILWAY

David Kindem and James Budzynski

Copyright 2015 by David Kindem and James Budzynski

ISBN 978-1-4671-1359-5

Ebook ISBN 9781439650592

Published by Arcadia Publishing

Charleston, South Carolina

Library of Congress Control Number: 2014948588

For all general information, please contact Arcadia Publishing:

Telephone 843-853-2070

Fax 843-853-0044

E-mail

For customer service and orders:

Toll-Free 1-888-313-2665

Visit us on the Internet at www.arcadiapublishing.com

This book is dedicated to the men and women who built and worked for the Grand Rapids, Grand Haven & Muskegon Railway, 19021928.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The Grand Rapids, Grand Haven & Muskegon Railway did not leave behind business records, so the information for this book has been assembled through the efforts of a number of individuals over the years. Without their support, this volume would not be possible.

Carl Bajema, our coauthor for an earlier book on this interurban line, spent years gathering information from newspaper archives and a variety of other sources that provide a framework for the story. Jack Rollenhagen spent a lifetime collecting the photographs that visualize the lines history.

Others include west Michigan local historians, former interurban employees, and their families who have contributed photographs, artifacts, and knowledge of the line and its practices. These include Fred Brown, Harry F. Brown, the Streeter family, Albert French, Claude Taylor, Clyde Tissue, Rachael Reister, Elizabeth Van Allsburg, Eleanore Drooger, the William Thielman family, the Jubb family, Ron Cochran, David Trealoar, Larry Cooke, Ruth Horton, the Orrie Sietsema family, Art and Joy Kulicamp, Denny Hoffman, Art Gibson, Jerre Jean McDaniels, and Mary Cuson.

Unless otherwise noted, all images appear courtesy of the Coopersville Area Historical Society Museum.

INTRODUCTION

In the late 1890s, Interurban Fever came to west Michigan. Promoters were busily forming companies to adapt the new and somewhat mysterious electric motors that powered city streetcars and use them to propel cars into the countryside and beyond. What the promoters offered was a vision of quiet, clean, electric cars providing frequent and comfortable service between the cities of Michigan. In 1898, such cars were already running between Detroit and Ann Arbor and from Saginaw to Bay City. Promoters roamed west Michigan, trying to establish potential routes before some other group snapped them up. Several such groups began to acquire land and franchises to connect Grand Rapids with Lake Michigan, focusing on the port cities of Muskegon, Grand Haven, and Holland.

One group was formed by Charles W. Taylor of Detroit, who teamed up with a pair of Grand Rapids attorneys, Thomas Carroll and Joseph Kirwin. Carroll, a director of the street railway system in Grand Rapids, saw an opportunity to use the technology to connect the city with the lakeshore.

The three promoters formed a company, the Grand Rapids, Grand Haven & Muskegon Railway, and began assembling property for their right of way. In search of additional funding, they turned to Detroit and approached Wallace Franklin, a former Grand Rapids resident. Franklin was the Midwest representative of Westinghouse, Church, Kerr & Company, an engineering subsidiary of the Westinghouse Manufacturing Company. The Westinghouse firm was already at work designing and building electric interurban railways to connect Detroit with Jackson and Toledo with Cleveland in Ohio. As an engineering firm, Westinghouse designed and built the railways for a fee (and, of course, specified Westinghouse components) but did not own them.

At Franklins suggestion, Westinghouse decided to back the group, but this time as owners, not just engineers. So, after a brief shuffling of personnel, the final company emerged, with Westinghouse firmly in control. Wallace Franklin recruited a friend and associate, James Dudley Hawks, as president. Hawks and Franklin had worked together to electrify the Detroit street railway in the early 1890s, and Hawks was the promoter of the DetroitAnn Arbor interurban, which Westinghouse, Church, Kerr & Company was building at the time. With Hawks as president, Carroll as vice president, Franklin as secretary, and Kirwin as treasurer, the group began to complete its plans and prepared to begin building the Lake Line.

The interurban cars would leave Grand Rapids using the tracks of the city streetcar system, then travel on private right of way through the communities of Walker and Berlin (now Marne). At this point, the tracks would parallel the Detroit and Milwaukee Railroad to Coopersville and Nunica. From Nunica, the company would build on the abandoned roadbed of the old Chicago and Michigan Lakeshore Railroad to Fruitport and then strike a straight line to the northwest toward Muskegon, where cars would enter using the Muskegon street railroad. A branch would also be built to Grand Haven from a junction just south of Fruitport.

In Coopersville, on September 20, 1900, Thomas Carroll turned the first shovelful of dirt, and the project was begun. Construction continued through 1901, as crews worked both east and west from Coopersville. The line was completed to Muskegon in January 1902 and to Grand Haven in June 1903.

By 1904, construction was complete, and the GRGH&M had settled into day-to-day operations. Wilmot K. Morley was recruited as general manager, and James Hawks returned to his other activities, which included an effort to connect the GRGH&M with Detroit, Ypsilanti, Ann Arbor, and Jackson via Lansing. But the Grand Rapids to Lansing section was never built.

The interurban represented something new: hourly cars moving quietly along their tracks that stopped to pick up passengers at road crossings, not just stations. A farmer in Berlin could make a trip to Grand Rapids after work. A Nunica resident could commute to Muskegon to work in a factory. A company in Grand Rapids could charter a car for an employee outing at a Lake Michigan beach.

Ridership increased throughout the early years, and the company made a small profit. Arrangements were made with the Goodrich and Crosby steamship lines for through passage on the interurban cars and the lake boats. Passengers could buy a ticket and check their luggage in Grand Rapids, and then pick their bags up in either Chicago or Milwaukee after an evening trip on the interurban and an overnight ride on a boat.

In addition to passengers, interurban cars carried packages and freight. A fleet of freight motors made scheduled trips to move less-than-carload freight between the towns on its route and transport goods to Chicago and Milwaukee via the boats. Express shipments, packages, newspapers, and US mail all moved via the interurban cars, whose frequent schedules made same-day service possible. Fruit and produce grown in the region was important cargo also. The GRGH&M moved vast quantities of crops to wholesalers and processors in Chicago and Milwaukee each year during the growing season.

Next page