A LSO BY S IDNEY D. K IRKPATRICK

The Revenge of Thomas Eakins

Edgar Cayce: An American Prophet

Lords of Sipan: A Tale of Pre-Inca Tombs, Archaeology, and Crime

Turning the Tide: One Man Against the Medellin Cartel

(with Peter Abrahams)

A Cast of Killers

First published in Great Britain in 2011 by Simon & Schuster UK Ltd

A CBS COMPANY

Copyright 2010 by Sidney Kirkpatrick This book is copyright under the Berne Convention.

No reproduction without permission.

All rights reserved. The right of Sidney Kirkpatrick to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988. Simon & Schuster UK Ltd

1st Floor

222 Grays Inn Road

London

WC1X 8HB www.simonandschuster.co.uk Simon & Schuster Australia

Sydney Photo credits appear on page 318 A CIP catalogue copy for this book is available

from the British Library. ISBN: 978-1-84983-202-1

eBook ISBN: 978-1-84983-208-3 Designed by Nancy Singer

Printed in the UK by CPI Cox & Wyman, Reading, Berks RG1 8EX

To Alexander Kirkpatrick

Man thirsts more for glory than for virtue. Armor of an enemy, his broken helmet, the flag ripped from a conquered ship, were treasures valued beyond all human riches. It is to obtain these tokens of glory that generals, be they Roman, Greek or barbarian, brave thousands of perils and endure a thousand exertions.D ECIMUS I UNIUS I UVENALIS,

R OMAN P OET OF THE S ECOND C ENTURY C.E.

CONTENTS

AUTHORS NOTE

The true story that follows is based on military records, correspondence, diaries, interviews, archival materials, and the unpublished World War II oral memoirs of University of California, Berkeley, art history professor Walter Horn.

CHAPTER 1

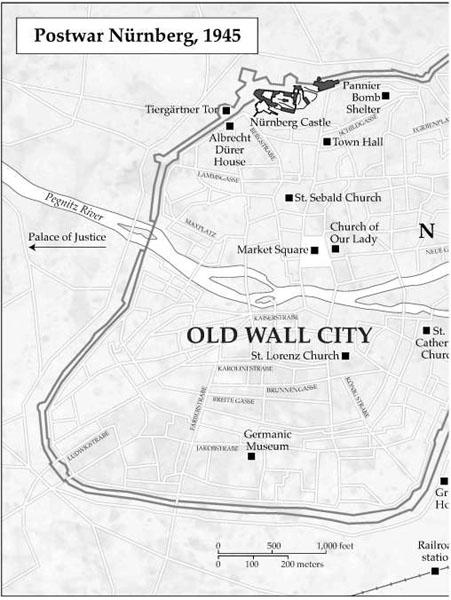

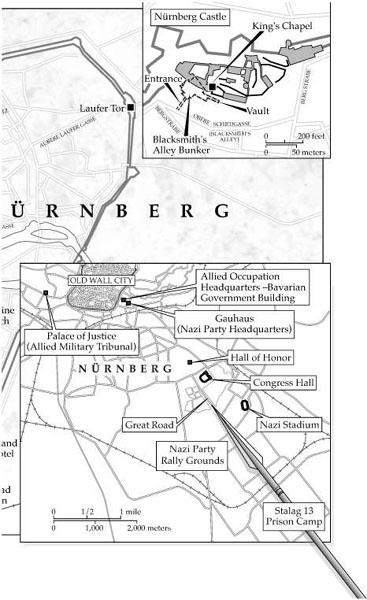

BLACKSMITHS ALLEY

February 23, 1945

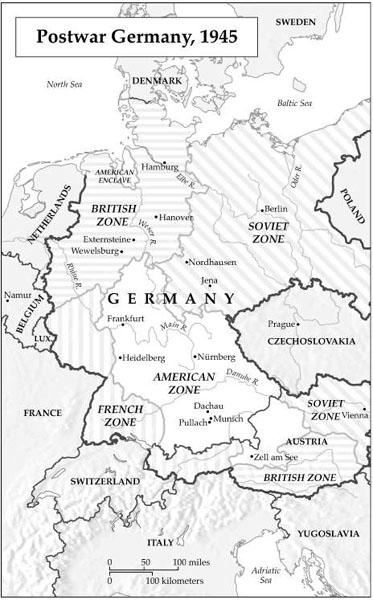

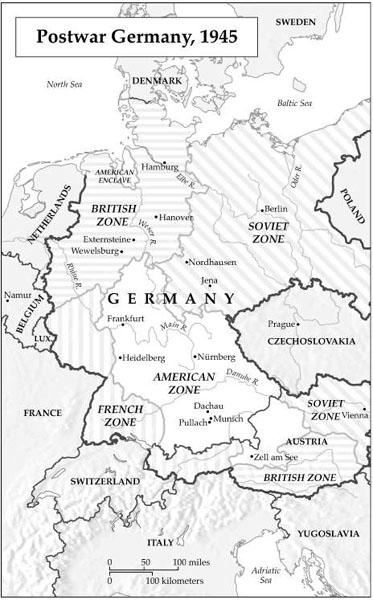

Every morning, like clockwork, Allied bombers would darken the skies over Namur, Belgium. In this last winter of World War II, hundreds and sometimes a thousand planes, flying in vast air armadas known as bomber streams, would thunder overhead for an hour or more at a time, leaving miles-long vapor trails that hung in the air long after the aircraft had vanished and the bombardiers had released their lethal cargo over targets in Germany and Eastern Europe.

The arrival of the bomber streams terrified the captured German soldiers at the U.S. Army detention center in the snow-covered fields on the outskirts of Namur. The prisoners, huddled together and shivering in wire-mesh holding pens, would peer anxiously skyward, dreading the horror about to be unleashed on their friends and families at home. Their American captors would also look up at the planes, but instead of fear, they felt overwhelming admiration for the bomber crews and their firepower. They were the silver hammer that was destroying the Nazi war machine and would soon enable the Allied Army to annihilate Adolf Hitler in his homeland. That the day and night bombing missions targeted not only military objectives but also industrial sites, resulting in the destruction of entire cities, was the price that Germany had to pay for its continued resistance.

First Lieutenant Walter Horn, one often German-speaking U.S. Third Army interrogators stationed at Camp Namur, awaited the daily arrival of the bomber squadrons with mixed emotions. Thirty-six years old, with a broad chest and shoulders, dark movie-star looks, and an impatient wife waiting at home in Point Richmond, on the San Francisco Bay, Horn felt tremendous pride in Americas ability to build, fuel, maintain, and launch thousands of planes loaded with tens of thousands of bombs, hurtling them hundreds of miles deep into enemy territory. Although he had yet to fire a weapon in combat during two years of service, and his mobile intelligence unit, commanded by General George S. Patton, always remained a comfortable fifty miles behind the front lines, Horn appreciated the daring and courage of the air crews and felt a special kinship with the thousands of othersartillerymen, infantry, medics, cooks, clerks, and quartermasterswho made up the largest, fastest-moving, and best-equipped army that had ever existed.

But the sight of the bomber streams also filled Horn with anxiety. Like the prisoners he interrogated, he had been born, raised, and educated in Germany. He never knew whether one of the bombers would be dropping its payload within range of his familys home in Heidelberg or if, as he looked into the holding pens at the forlorn faces of captured and wounded prisoners, he would one day see the face of his older brother Rudolf.

Lieutenant Horns orders that winter were to help ascertain whether Hitler would unleash chemical or biological weapons when the Allied Army crossed the Rhine River into the German heartland. It had been rumored that the Germans, in a last desperate attempt to break the vise of the approaching Allied forces, would resort to using such weapons, as they had in the trenches in France twenty-seven years earlier.

Pattons mobile intelligence unit had prepared a detailed questionnaire to ferret out the truth. Interrogators did not ask prisoners directly about weapons stockpiles. Rather, they elicited the information from four out of one hundred fifty seemingly random questions put to the prisoners. The answers would be used to determine if the soldiers had been taught how to use chemical or biological weapons in battle and if, hidden behind enemy lines, shelters were in place to protect the civilian population. Fifteen hundred rank-and-file soldiers, selected from Wehrmacht infantry captured in Belgium after the Battle of the Bulge, had been marched to Namur for this purpose. The interrogation facilities being inadequate, many of the interviews took place out of doors. Horns office, just beyond the prisoner enclosures, consisted of two empty orange crates, a small desk borrowed from a nearby elementary school, and a stack of questionnaires and pencils.

Horn had already interviewed thirty-five prisoners on February 23, 1945, when a camp guard brought him forty-eight-year-old Private Fritz Hber from the German 2nd Panzer Division. Lean and haggard, with a narrow face distinguished by an enormous hooked nose, Hber wore the same ill-fitting uniform in which he had been captured three weeks earlier. Though old by Allied Army standards, Hber was not an unusual Wehrmacht recruit, as the Germans, after more than five years of continuous warfare, were drafting soldiers as young as sixteen and as old as sixty, mixing them into units of battle-hardened veterans and having them dig trenches, run interference, and haul equipment on their backs or in carts. German manpower, a resource like the diesel fuel to drive their tanks, was now in short supply.

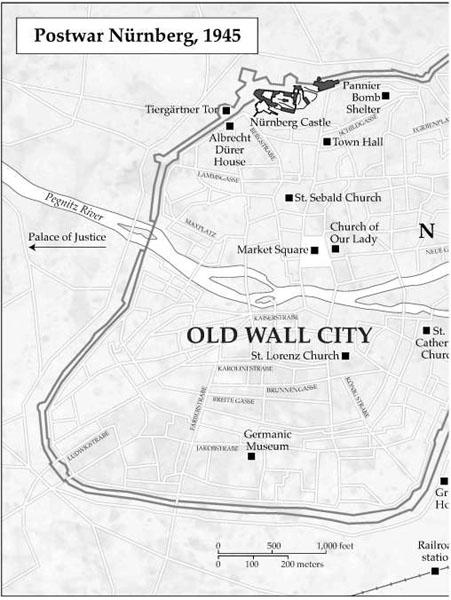

Hber, recruited in Nrnberg, had received less than a months training before being marched through the snow into combat in Belgium; he didnt know anything about chemical or biological weapons. Horn checked off the privates answers in rapid succession, obtaining nothing more than yes, no, and I dont know.

Next page