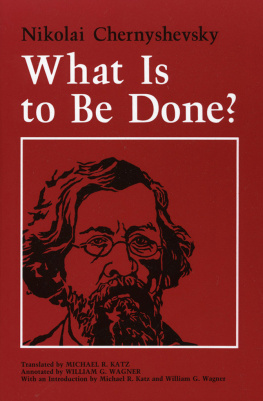

Nikolai Chernyshevsky - What Is to Be Done?

Here you can read online Nikolai Chernyshevsky - What Is to Be Done? full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 1989, publisher: Cornell University Press, genre: Science fiction. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:What Is to Be Done?

- Author:

- Publisher:Cornell University Press

- Genre:

- Year:1989

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

What Is to Be Done?: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "What Is to Be Done?" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

What Is to Be Done? — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "What Is to Be Done?" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

CHAPTER ONE

Vera Pavlovna had a very ordinary upbringing. Her early life, before she made the acquaintance of the medical student Lopukhov, contained a few noteworthy events, but nothing unusual. Even then, however, her behavior showed itself to be somewhat exceptional.

Vera Pavlovna grew up in a multistoried house on Gorokhovaya [Pea] Street, between Sadovaya [Garden] Street and the Semenovsky Bridge. At the present time this house is designated by an appropriate number, but in 1852, when there were no such numbers, the house carried the inscription: Residence of the Councillor of State Ivan Zakharovich Storeshnikov. Thats what the inscription said; but Ivan Zakharovich Storeshnikov had died in 1837 and since then the house had belonged to his son, Mikhail Ivanovichor so the legal documents indicated. But the tenants knew that Mikhail Ivanovich was only the former owners son, and that the real proprietor was his widow, Anna Petrovna.

Then, as now, the house was large; it had two gates, four doorways onto the street, and three courtyards within. In 1852, just as now, the owner and her son lived in the rooms on the ground floor with their windows looking out on the street. Anna Petrovna remains just as handsome a woman now as she was then. Mikhail Ivanovich is just as handsome an officer now as he was then.

I dont know who now resides in the fourth-floor apartment to the right atop the filthiest of the many back staircases off the first courtyard. But in 1852 these rooms were inhabited by the manager of the building Pavel Konstantinych Rozalsky, a portly, handsome man; his wife, Marya Aleksevna, a tall thin, sturdy woman; their daughter, a young unmarried woman, none other than Vera Pavlovna; and their nine-year-old son, Fedya.

Besides being the manager of the building, Pavel Konstantinovich worked as an assistant to the head of a government department. He received no income from this position, and only a modest one from being manager. Anyone else would have earned much more, but as Pavel Konstantinych himself used to say, he had his scruples. The landlady, however, was entirely satisfied with him. During his fourteen years of managing he had managed to accumulate a sum of about 10,000 rubles. No more than 3,000 or so had come from the landladys pocket; the rest he had acquired at no cost whatever to his employer. Pavel Konstantinych was a pawnbroker.

Marya Aleksevna also was in possession of a tidy bit of capital5,000 rubles or so, as she used to tell her fellow gossips, but in fact it was more than that. The origin of her capital dates back some fifteen years to the sale of a raccoon coat, miscellaneous scraps of clothing, and assorted bits of furniture that she had acquired at the death of her brother, an office clerk. Having realized a profit of some 150 rubles, she likewise put the money back into circulation by accepting pledges as collateral, taking far greater risks than her husband ever did. Several times she got caught at her own game. Once a swindler borrowed five rubles from her and left his passport as a pledge; it turned out to be stolen and Marya Aleksevna had to lay out an extra fifteen rubles to extricate herself from that affair. Another scoundrel once pawned a gold watch for twenty rubles; it turned out to have been lifted from a dead body and Marya Aleksevna had to hand over quite a hefty sum to get herself out of that mess. But if she suffered losses that her husband managed to avoid (since he was more discriminating in his choice of clients), she also realized greater profits. She even sought out special opportunities for making money. Once, when Vera Pavlovna was still very young Marya Aleksevna never would have done it when her daughter was older, but there was absolutely no reason not to do it back then; the child would never have understood, thank you very much, if it hadnt been for the cook, who explained the whole thing to her very clearly. And the cook would never have done so, since it wasnt right to talk about such things to children, but it happened that the cook couldnt restrain herself after one of the worst beatings shed ever received at the hands of Marya Aleksevna following a little fling with her boyfriend. (By the way, Matryona always sported a black eye, not from Marya Aleksevna but from her boyfriendwhich was all right, since a cook with a black eye comes cheaper!) Be that as it may, An acquaintance of mine, Savastyanovaa merchants wife from Pskovand thats all! Finally, after a good bit of swearing, the civilian left and never returned. Verochka witnessed the whole affair when she was eight years old; when she was nine, Matryona explained it all to her. However, there was only one such episode; others were different and not very frequent.

Once, when Verochka was ten and was accompanying her mother to the flea market, she received an unexpected wallop across the back of her head at the intersection of Gorokhovaya and Sadovaya streets along with the explanation : Instead of gawking at the church, you idiot, why dont you cross yourself? Cant you see that all good people cross themselves?

When Verochka was twelve she began to attend private school. She also started taking piano lessons from a drunken but very kind German piano teacher. He was a good teacher, and very inexpensive as a result of his drinking.

When she was fourteen she did the sewing for her entire family; bear in mind, of course, that the family wasnt all that large.

When she was about to turn sixteen, her mother started shouting at her in the following manner: Scrub that face of yoursyoure as dark as a gypsy girl! Youll never get it clean! I must have given birth to a scarecrowI dont know who you take after. Verochka put up with a great deal on account of her dark complexion and had become quite accustomed to think of herself as homely. Previously her mother had dressed her in rags, but now she began to spruce her up a bit. This better-dressed Verochka who accompanied her mother to church used to think, These clothes would better suit someone else. Whatever I wear, Im still a gypsy girl, a scarecrowwhether Im in a cotton frock or a silk dress. It would be nice to be pretty. Oh, how Id like to be pretty!

When Verochka turned sixteen, she ceased taking piano lessons and stopped attending private school; instead, she began giving lessons in that very same school. Soon her mother found other pupils for her as well.

After six months or so Verochkas mother stopped calling her a gypsy girl and a scarecrow and began to spruce her up even more. Meanwhile Matryonathis was already the third one after the aforementioned Matryona (the originals left eye was always blackened, whereas the replacements left cheekbone was usually, but not always, bruised)this third Matryona told Verochka that the head of her fathers department, an important department head who wore an order around his neck, was planning to propose to her. Indeed, the petty clerks reported that the department head had of late become better disposed toward Pavel Konstantinovich. The department head, in turn, began to express the opinion in the presence of his relatives that what he needed most was a good-looking wife, even if she didnt have a dowry, as well as the opinion that Pavel Konstantinych was not that bad a clerk.

Its not clear how all this would have ended, but the department head deliberated for a very long time and very judiciously... so that in the meantime another opportunity presented itself.

The landladys son dropped in on the manager to say that his mother wanted Pavel Konstantinych to collect samples of various wallpapers, as she was planning to redecorate her apartment. Such requests had previously been communicated through the butler. Obviously the purpose of this visit would have been immediately apparent even to less worldly-wise folk than Marya Aleksevna and her husband. The landladys son came and stayed for more than half an hour; he even deigned to have a cup of tea brewed from the choicest leaves. The very next day Marya Aleksevna presented her daughter with a necklace left as an unredeemed pledge; she also ordered two fine new dresses for her. The material alone cost 40 rubles for the first, 52 for the second; together with cutting, flounces, and ribbon the two dresses came to 174 rubles. At least thats what Marya Aleksevna told her husband, while Verochka knew that she had spent a total of less than 100 rubles (after all, she was present at the purchase); but two extremely fine dresses can be made for 100 rubles. Verochka was delighted with them and with the necklace, but most of all she was delighted that her mother at long last had agreed to start buying her shoes at Korolyovs. Shoes from the flea market were so ugly, while those from Korolyovs fitted ones feet so beautifully.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «What Is to Be Done?»

Look at similar books to What Is to Be Done?. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book What Is to Be Done? and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.