About the Author

Patricia Eichenbaum Karetzky is O. Munsterberg Chair of Asian Art at Bard College, New York, and adjunct professor at City College of New York. She has published numerous books and articles on Chinese culture in general, and particularly on Chinese religious art, notably Buddhist and Daoist aesthetic traditions. She was editor of the Journal of Chinese Religions for five years.

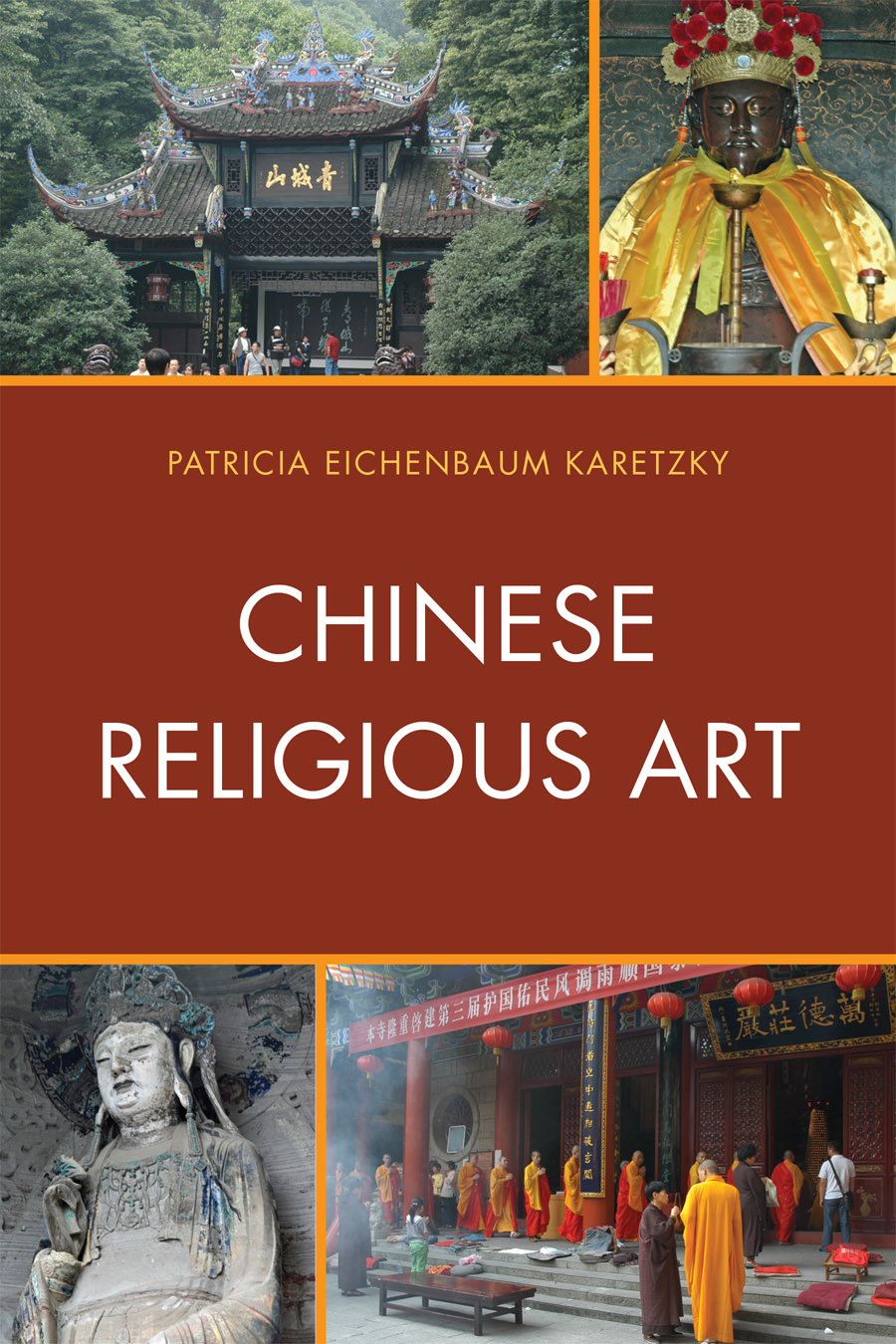

Chinese Religious Art

Introduction

This study concerns the origins and development of religious art in China. The sheer scope of the subject is daunting, and perhaps this is the reason others have not endeavored to cover a subject that is so complex, broad, and long in duration. In the last two decades, scholarship in the fields of Chinese religious studies and art has mushroomed, and though one celebrates the wealth of information and new methods by which to analyze the great religious traditions of China, keeping up with the new materials is time-consuming and challenging. Notwithstanding the difficulty of the task, a sustained study is, nonetheless, worthwhile, for it allows us to view the development of Chinese religious art. In this overview, the interrelationship and interdependence of these traditions becomes readily apparent. Cultural context plays a significant role in the evolution of religious thought. Political circumstances and the wave-like patterns of Chinese history, with periods of foreign conquest and national restoration, have instigated vast changes in belief and expression.

This book hopes to offer the first survey of the subject. Although the extant literature is rich, no works cover the whole of Chinese religious art. Those that explore Buddhist art, though insightful, are limited in scope. Often such works begin with the introduction of Buddhism into China and trace its interaction with Chinese culture and subsequent progress; scholarly efforts interpret the meaning of Buddhist iconography, the development of various schools, regional expressions, and stylistic evolution. Daoist art has only recently received the attention it richly deserves.

Traditionally, studies of Chinese religious art focus on the art of a specific religious tradition, or period, or type of art, and often the artwork is excerpted from its context. But consideration of the architectural environment is essential to a full appreciation of the manner in which viewers experienced murals, altars, and icons. So it seems important to consider architecture as the context for the art and rituals. This text also hopes to demonstrate the value of religious art to the field of religious studies. Pictorial traditions have only recently been addressed as a viable source of information, though still not as highly regarded as exegetical studies or field work. When images are employed they are often examined as the pictorial expression of some doctrine or ritual practice, while other insights and reflections of the religion and the culture in which it exists are not considered. Moreover, artistic or technical qualities are not taken into account. Two reasons for the emphasis on scriptures are the sacred nature of the texts and the fact that literary expression usually precedes visual expression by centuries, with the possible exception of esoteric art, in which images are considered an integral part of ritual. But as Poul Andersen has explained, images also have a language that can be deciphered. In sum, this study of religious art presents a means of analyzing pictorial manifestations of the divine.

There are four parts to this study. Part 1 concerns the earliest evidence of religious ideas that begins in the Neolithic period. Ancient religious expression is fundamental to the formation of a religious ideology and the world view that followed. One detects a continuity of these concepts in the material evidence. This section ends with the reign of the First Emperor Qin Shihuangdi (r. 221210 BCE), for it is only after this era that Confucianism and Daoism undergo their first stage of development into institutional religions and one can analyze the nascent artistic expression of their traditions. Part 2 considers Confucianism, beginning with the Han dynasty (206 BCE220 CE), as it became the basis of the state ideology. The emperor and his court took control of religious activity on behalf of the state, setting a precedent that was largely observed for the next two thousand years. Confucianism can be viewed as a religious tradition based on sacred texts, rituals, liturgies, temples, icons, and pictorial expression of its ideology. Confucianism also provides the broad framework of Chinese aesthetics, which is the foundation of all subsequent artistic expression, secular or religious. In this study, Confucianism comprises the teachings of Confucius, the imperial institutions and rituals associated with the state that were founded on its ideology, the canon of its texts (which was the basis for state bureaucratic examinations), and later a religious institution with temples and icons for reverence of the person of the sage.

Part 3, Daoist Art, begins at the end of the Han dynasty with the birth of religious Daoism and its art. Later in the medieval period, several regional schools emerged, offering different transmissions of sacred texts and means for achieving spiritual unity with the universe. Monastic establishments also appeared at that time. With the reunification of China under the native Tang dynasty (618907), a growing conformity was observable among the variant schools. In the Song dynasty (9601279) and Yuan dynasty (12791368) new sects developed, requiring different forms of art for their rituals. With the growth of Daoism and the burgeoning of artistic production in the Ming dynasty (13681644), the number and kinds of Daoist art proliferated in diverse formats and media; ceramic, lacquer, glass and wooden objects bear imagery associated with its practice. Buddhism, the subject of Part 4, was introduced into China during the late Han dynasty, but it was not until the medieval period that it enjoyed imperial support and commissions for large-scale projects. By the time Buddhism entered China, it was already a highly evolved and institutionalized religion. Buddhism was not a monolithic entity but rather a conglomeration of teachings and practices; most schools of Buddhism shared a rich cultural package that included thousands of sacred texts, an iconic anthropomorphic tradition, and narrative art and several architectural forms including temples, stpas, monasteries, and gardens. These had a palpable impact on the other religions.

This overview of Chinese religious art considers changes in worship, icons, and architecture in tandem with a general appreciation of historical and political events. Also observed are artistic developments, for, as will be seen, there was a steady stream of formats and styles. This investigation begins with a chronological survey of developments in religious thought followed by a discussion of the art and architecture of the period. The last chapter of each section is given over to the most important or distinctive temples. Despite their great antiquity, many are recent constructions or ancient ones that have undergone extensive renovation. Naturally, for the earlier chapters material evidence is scanty, and in later periods, more examples are available for analysis. Therefore, chapters vary in length.

A chronological study of the artistic manifestations in tandem with each other would have been, no doubt, a valid means of organizing the material. But viewing each artistic tradition separately has the benefit of providing a single, focused study that stresses continuity and change over the centuries.