Contents

AN INTRODUCTION TO

SPLENDOR SOLIS

Stephen Skinner

HISTORY AND AUTHORSHIP

OF SPLENDOR SOLIS

Rafa T. Prinke

INVENTING AN ALCHEMICAL

ADEPT: SPLENDOR SOLIS AND

THE PARACELSIAN MOVEMENT

Georgiana Hedesan

COMMENTARY ON THE TEXT AND

PLATES OF SPLENDOR SOLIS

Stephen Skinner

TRANSLATION OF

THE HARLEY MANUSCRIPT

Joscelyn Godwin

GLOSSARY OF ALCHEMICAL

PHILOSOPHERS AND WORKS

REFERRED TO IN SPLENDOR SOLIS

Georgiana Hedesan

An Introduction to

Splendor Solis

Stephen Skinner

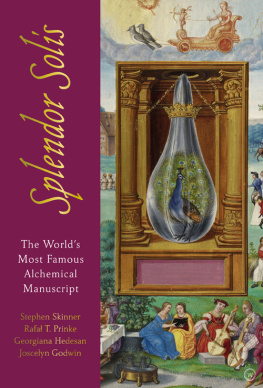

Of all the illustrated alchemical texts perhaps the best known is the 16th-century Splendor solis. With its richly allegorical artworks and detailed instructions on the Great Work of transmuting a base material (prima materia) into the Philosophers Stone, this manuscript immerses the modern reader into the mind of the Renaissance alchemist. Despite this, until now there has been no reasonably priced edition offering both a full English translation and reproductions of all the plates in colour. Most current editions of Splendor solis are reproductions of a 1920 black-and-white version. By issuing this full-colour volume, complete with a new translation by Joscelyn Godwin of the definitive version of the manuscript (Harley MS 3469) held in the British Library, we hope to correct this deficiency.

This edition also includes my overview of the colour plates and original text, to aid navigation and uncover some of the manuscripts meaning, as well as illuminating essays by Rafa T. Prinke, on the latest research into the history and authorship of Splendor solis, and Georgiana Hedesan, on the links between Splendor solis and the renowned Swiss physician, alchemist and astrologer Paracelsus. Georgiana Hedesan has also provided a useful glossary of the alchemical philosophers and works referred to in Splendor solis.

Splendor solis in the 20th century

Splendor solis underwent something of a revival in the early 20th century, largely thanks to the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, a magical order founded by three adepts in 1888. One of these, S. L. MacGregor Mathers, wrote many of the rituals and researched and published a number of works, including several grimoires (magicians handbooks). Among the early members of the Golden Dawn was the alchemist and minister Rev. W. A. Ayton. It seems that Mathers and Ayton were both interested in Splendor solis. Mathers is even reputed to have published an edition of the text in 1907, incorporating his notes on the Kabbalistic and Tarot implications of the text and its alchemical symbolism, but sadly I have not been able to find a copy. was a pupil of Ayton.

Kohns edition did not receive much attention, and it was not until the advent of universal colour printing in the late 20th century that colour reproductions of the plates in Splendor solis began to appear. Kohns translation has interpolated references to the Tarot. He did considerable research into alchemical manuscripts in the Bodleian Library, one of which contains translations by the 17th-century antiquary Elias Ashmole of some essays credited to Trismosin. Kohn was also interested in plant-based alchemy and magnetic and odic medicine, which were popular in the early 20th century.

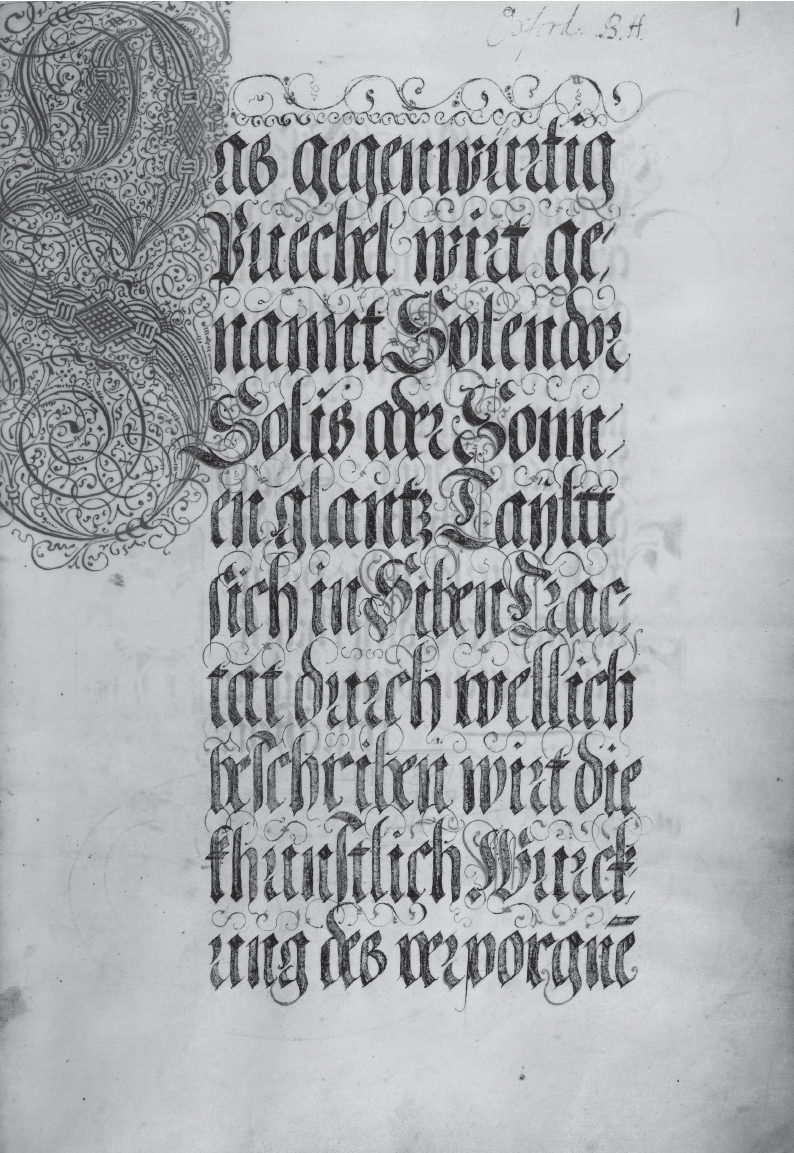

The title page [f.1r] of the manuscript of Splendor solis held in the British Library (Harley 3469).

The other 20th-century milestone in the life of Splendor solis was the limited edition published in 1981 by Adam McLean in his excellent Magnum Opus Hermetic Sourceworks series, and reissued in 1991 by Phanes Press, with a commentary by Adam. This edition had one shortcoming: the illustrations were black-and-white line drawings from an earlier edition printed in Hamburg, with much less detail than the manuscript published in the present volume. Whats more, the Latin text that appears on some plates was omitted by the German engraver, along with the beautiful and elaborate borders overflowing with symbolism. And the translation included in that edition was of a version of the text inferior to the Harley MS 3469.

A LIFELONG FASCINATION

My own interest in alchemy dates back to my teen years when I enjoyed browsing the mysterious images often associated with this art. Looking at, for example, the 17th-century alchemical text the Mutus Liber, literally the Silent Book, with its strange succession of images or emblems stirred me to embark upon a quest to see as many alchemical images as possible, hoping that in the end they would all make sense.

I was also intrigued by the series of emblems I found in Atalanta fugiens (1617) by Michael Maier, a German doctor of medicine, and self-styled Count of the Imperial Consistory and Free Nobleman. A series of tantalizing epigrammatic verses accompanied each emblem but these, if anything, increased the mystery rather than solving it. The subtitle Emblemata nova de secretis naturae chymica promised new emblems of the secrets of natural chemistry. There were drawings of salamanders and secret gardens, kings beheaded, burned, drowned and buried. Looking back at this text published just 35 years after the manuscript of Splendor solis here reproduced, I can clearly see a number of parallels, such as a double fountain, a king swimming and a hermaphrodite. Such emblems percolate through the history of alchemy, but dont always mean the same thing this is both the charm and challenge of interpreting these texts. The alchemists never wanted to make this process easy.

At the same time, I developed an interest in Dr John Dee, mathematician to Queen Elizabeth I, and his colleague Edward Kelley, who claimed to have found in Glastonbury a flask of red powder and the alchemical book of St Dunstan. With the red powder he and Dee demonstrated various examples of transmutation of base metals into gold. Such claims are not unique and seldom believable, but in this case Kelley and Dee freely admitted that they could not produce the red powder of projection itself, but only knew how to use it. After splitting from Dee, Kelley later became rich and famous enough to be knighted by Rudolf II of Bohemia, which gives some evidence of his skills as an alchemist. There was even a fairly wellattested story of his having transmuted half of a copper warming pan, leaving the gold side attached to the remaining copper side. Such stories piqued my curiosity and made me more certain that alchemy was at heart a physical art and not just an academic game of images and emblems.

It wasnt until the mid-1970s that I finally came across a practitioner who was actually doing these experiments with real chemical equipment. He introduced himself simply as Lapidus and made me swear not to reveal his identity. He owned a furriers shop in London, close to Baker Street underground station. In the cellars of his shop he had fitted out a modern alchemists laboratory and was following the classics like Pontanus, Artephius and Ali Puli step by step. As we will see later, one of the main indicators of success for the ancient alchemists was a particular sequence of colour changes. I was fascinated to see that Lapidus had indeed succeeded in replicating that sequence and reaching a point close to the conclusion of the operation. By using laboratory heating devices, which could maintain a specific temperature, without fluctuation, for long periods of time, rather than relying on unreliable assistants to stoke and damp a coal furnace, he avoided the hazards that plagued the ancient alchemists. He also avoided frequent breakages of glass equipment by using modern Pyrex cucurbits and flasks. Nevertheless, he had many false starts before he decided that the operation must begin with a specific metallic ore.