First published by Context, an imprint of Westland Publications Private Limited, in 2019

1st Floor, A Block, East Wing, Plot no. 40, SP Infocity, Dr. MGR Salai, Perungudi, Kandanchavadi, Chennai 600096

Westland and the Westland logo, Context and the Context logo are the trademarks of Westland Publications Private Limited, or its affiliates.

Copyright Dhirendra K. Jha, 2019

ISBN: 9789388689410

The views and opinions expressed in this work are the authors own and the facts are as reported by him, and the publisher is in no way liable for the same.

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced, or stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without express written permission of the publisher.

In Mas Memory

CONTENTS

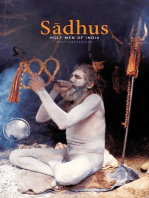

L et him die, said the sadhu, kicking the belly of an old man lying injured on the ground. Half-a-dozen other sadhus surrounding the pair roared their approval by banging their lathis on the ground and their fists on whatever surface they could find. Two police constables standing hardly ten metres from the main gate of Ayodhyas Hanumangarhithe command post of Nirvani akhara, a major militant ascetic order of the Vaishnava secttalked among themselves as if they had noticed nothing. A small crowd of over a dozen men and a few children stood watching from a safe distance. Only after the white-clad inmates of Hanumangarhi walked away did the cops dare to look at the old man, who was struggling to get up and was bleeding profusely from his mouth.

Save me, the old man mumbled through his broken teeth as the sadhus departed. I never meant The words died in his throat. Give me some water, he finally managed. Moments later, his chest heaved and he lost consciousness.

It was a December evening in 2010. A fellow journalist and I had been on our way back after a days work when we came upon this scene. We were too stunned to move, and the other onlookers looked scared. The cops still pretended not to have seen anything. The only sound was the soft sobbing of a boy, around eight or nine years of age, trying to comfort the old man, perhaps his grandfather.

We learnt later that the old man was a vendor of rose petals and marigold garlands in a shop owned by Hanumangarhi. He had not been able to pay the rent for the last two months, and the sadhus of Hanumangarhi had set out to not only punish him but also send out a message to the others. The old man was taken to a local government hospital, and he survived.

My colleague and I were in Ayodhya to try and unearth the lost details of the night of 22 December 1949, when an idol of Lord Ram was planted surreptitiously in Babri masjid by a little-known sadhu of Hanumangarhi, Abhiram Das, and his followers. The incident left a permanent scar on the Indian polity, and yet the story of how the sixteenth-century mosque was occupied and claimed as a temple was missing from the tellings of modern Indias history.

But after witnessing the brutality meted out to that old man, I spent hours in and around Hanumangarhi over the next couple of days, trying to understand this blatant display of violence by men who were supposed to be devout ascetics. Neither the brutal use of power on an unarmed old man that evening nor the surreptitious planting of the idol by Abhiram Das back in 1949 corresponds to the asceticism that the sadhus of Hanumangarhi claim to practise. It took a great deal of research, investigations and interviews to understand this rupture. What I found in Hanumangarhi was not a world informed by the spiritual strength of its ascetics but one formed by the brute force of syndicates of armed sadhus who fight among themselvessometimes even engaging in open battlesfor wealth and power. They take care not to disturb Hanumangarhis veil of asceticism even as they merge seamlessly with the business end of things, the state and the openly communalist Hindu Right.

There was a time when the sadhus of Ayodhya were bohemian, by and large, and at least the clever ones took care to keep the veil of spirituality on. But the Hanumangarhi residents I encountered that evening had brazenly displayed their power. The longer I worked to understand this new culture, the clearer it became that it was part of a larger malaise, which started to become dominant around the 1980s when the Vishva Hindu Parishad (VHP), or World Hindu Council, launched a massive drive to use sadhus for the religio-political mobilisation of Hindus. When I expanded the area of my research to places like Haridwar, Varanasi and Allahabad, I realised that this change in the sadhus attitude was prevalent outside of Ayodhya as well.

What is this new culture, then? How is it born? And why is it nurtured by forces eager to promote Hindu supremacist politics? These questions became the focus of my inquiry as I delved deep into the world of Hindu monastic orders.

This book is not about the spirituality of sadhus and the influence they wield over lay devotees. Nor is it about their rituals, belief systems and monastic orders. Rather, it is an inside view of the sadhus, not as keepers of sacred knowledge but as men who play games for power, money and influence. It is about the organisation and politics of their hidden world and how this has been changed and exploited by the Hindu Right. It is about why these men, and the few women, do what they do and how the double lives they lead affect them. Perhaps the answers to these questions could reveal why we are so often confronted with the worst of sadhuslike the one who became a business tycoon by selling yoga and medical advice along with a strong dose of Hindu pride or the other who was convicted for the rape of a minor girl or yet another who experienced nirvana through political power.

H induism does not have a central authority or an overarching church-like organisation. Monastic orders that belong to a great number of sampradayas, or traditions, are at the core of this religion. The sadhus in these sampradayas, most often celibate monks, act as spiritual leaders for the lay followers. They are expected to offer religious discourses and promote practices that defend the centrality of the guru-bhakti tradition. Devotees believe that adhering to their teachings brings peace, prosperity and meaning in life and, eventually, salvation. Monastic orders of the Vaishnava or Shaiva traditionsVishnu or his incarnates, like Ram or Krishna, are the principal deity of the former, and Shiva of the lattercontrol most of the ascetic space of Hinduism. Their strength is showcased in the largest Hindu religious gathering, the Kumbh Mela, held every twelve years in each of the four citiesAllahabad, Haridwar, Nasik and Ujjainwhich commands worldwide media attention, particularly the bathing procession of naked Shaiva sadhus.

The two monastic orders have their own sets of mutts and ashrams, some of which have ambiguous institutional and power hierarchies, while others work autonomously. But all of them are ultimately linked to their respective akharas, originally conceived as the militant wing of Hindu monasticism. Akharasthe name refers to the wrestling pit attached to them, which largely fell into disuse after the rise in the use of firearms in the 1980sare large military-style camps of sadhus. In the past, these akharas were centres of warrior ascetics and enjoyed proximity to princely rulers and their courts. But now, as the nodal organisations of various monastic orders of Hinduism, they are the main organisers of the Kumbh Mela, where, in the presence of millions of pilgrims and devotees, sadhus showcase and celebrate their former glorious past. The nagas are a big part of this celebration.

Next page