ALSO BY MARY GORDON

Fiction

The Stories of Mary Gordon

Pearl

Final Payments

The Company of Women

Men and Angels

Temporary Shelter

The Other Side

The Rest of Life

Spending

Nonfiction

Reading Jesus

Circling My Mother

Good Boys and Dead Girls

The Shadow Man

Seeing Through Places

Joan of Arc

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the authors imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Copyright 2011 by Mary Gordon

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

Pantheon Books and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to HarperCollins Publishers for permission to reprint an excerpt from the Second Duino Elegy by Rainer Maria Rilke, from A Year with Rilke: Daily Readings from the Best of Rainer Maria Rilke by Joanna Macy and Anita Barrows, copyright 2009 by Joanna Macy and Anita Barrows. Reprinted by permission of HarperCollins Publishers.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Gordon, Mary, [date]

The love of my youth / Mary Gordon.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-0-307-37977-1

1. First lovesFiction. 2. Middle-aged personsFiction.

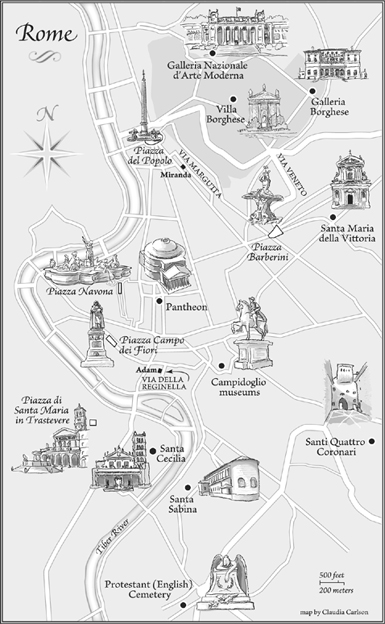

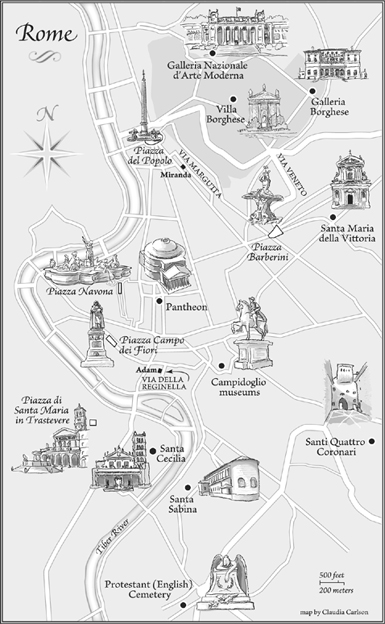

3. Rome (Italy)Fiction. I. Title.

PS 3557.0669 L 68 2011 813.54dc22 2010032988

www.pantheonbooks.com

Jacket image: The Ponte Giuseppe Mazzini in Rome by Rob Koenen/Flickr/Getty Images

Jacket design by Carole Devine Carson

v3.1

For Penny Ferrer

We have come this far

This is given to us, to touch

each other in this way.

Rainer Maria Rilke,

from the Second Duino Elegy

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Gail Archer and Richard Goode for advising me on matters musical. Also I would like to thank everyone who has opened to me the joys of Rome.

My time in Rome was made possible by research funds provided by the Millicent C. McIntosh Chair in English at Barnard College.

Contents

October 7, 2007

I hope it wont be strange or awkward. I mean, what seemed strange to me, or would seem strange, is not to do it. Because in a way it is strange, isnt it, really, the two of you in Rome at the same time, the both of you phoning me the same day?

Irritation bubbles up in Miranda. Had Valerie always been so garrulous? So vague? Had she, Miranda, always found her so annoyingthe qualifications, the emendations, laid down, thrown out like straw on a road to muffle the noise of passing carriages when thered been a death in the house? Where did that come from? Some novel of the nineteenth century. The early twentieth. And now it is the twenty-first, the first decade nearly done for. Theres no point in thinking this way, focusing on Valeries habits of speech and diction. As if that were the point. The point is simply: she must decide whether or not to go.

It has been nearly forty years since she has seen him. Or to be exactand it is one of the things she values in herself, her ability to be exactthirty-six years and four months. She saw him last on June 23, 1971. The day had changed her.

Adam tries to remember if he had ever been genuinely fond of Valerie. What he can recall is that, of Mirandas many friends, Valerie was the one who seemed most interested in him. The one who asked him questions and then listened to his answers, who assumed he had a life whose details might be worthy of her attention. 1966, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71. A time when he spent his days trying to determine the perfect fingering, the ideal tempo, for a Beethoven sonata, a Bach partita. A way of spending time that Mirandas friends considered almost criminally beside the point. The point was stopping the war. Stopping racism. Stopping poverty. Diminishing the injustice of the world.

In those days, he couldnt speak to anyone about his pain over the fact that Miranda seemed entirely taken up by the problems of the world. The things that absorbed him no longer captured her attention. Not that he ever wanted to capture her attention; her attention was not a bird he was trying to snare, a fish he was netting. For that was what he loved most about Miranda: her minds speed, but not only her mind, her quickness in everything. Darting, swooping, leaping, thrilling to him, who moved so slowly, whose every gesture was considered. Those who criticized his playing of the piano accused him of being incapable of lightness. She was a bright thing, a shimmering thing, a kingfisher, a dragonfly. Thirty-six years later she would be no longer young. Had she kept her quickness? Her lightness? Which would he have preferred, that she had kept or lost them?

Is that why hes agreed to it, to seeing her after all these years, at this dinner Valerie has arranged? Out of simple curiosity? Along with lacking lightness, he has been charged with lacking curiosity. But perhaps both had always been untrue. That curiosity has in this instance triumphed over shame: this must be a sign of strength. For if his soul is, as hed learned in Sunday school, a clear vessel that could be blackened by his sins, what he did to Miranda was among the blackest. When he told himself he couldnt have helped it, that he had done the best, the only thing he could have done under the circumstances, the words rang false. He would be tempted to say that to her now, but he would never say it. He is hoping there will be no need. That they will see each other once again, no longer young but healthy, prosperous, intact. That he will see the proof: that he did not destroy her.

She stands before the spotted mirror. A dime-sized pool of expensive moisturizerrose scented, ordered especially from a Romanian cosmetician in New Yorkspreads in the heat of her palm. Miranda wonders what Adam looks like. She tries on a long black skirt, throws it impatiently on the bed, then Nile green silk pants with wide legs. She tries on the black skirt again. Then a violet knit top, which she rejects because it emphasizes her breasts. Once a vexation to her on account of their smallness, her breasts had done all right with age. Shes glad he wont be seeing her naked. Or in a bathing suit. Well, she is nearly sixty now, and her body shows the marks of bearing two strong healthy sons. Her legs, which, he had said, caused him a desire that was painful in its intensity when he saw them in her first miniskirtSeptember 1965but which shed always thought too thick, too straight, these had gone flabby. Shes triedswimming, running, yogabut nothing really helps. Most of the time she doesnt think of it, she doesnt really care. Its one of the benefits of age: such things have lost their power to scald.

Shes blonde now; he would not be accustomed to thinking of her as a blonde, and her hair is short, boyish. In the time they knew each other her hair had hung down her back at one point almost to her waist. Her hair was brown then, a light brown; hed called it honey colored. Shed parted it in the middle or braided it into a single plait. Then she remembers: he did see her, briefly, with boyish hair. She doesnt like to think about that time.