The book you are holding came about in a rather different way to most others. It was funded directly by readers through a new website: Unbound. Unbound is the creation of three writers. We started the company because we believed there had to be a better deal for both writers and readers. On the Unbound website, authors share the ideas for the books they want to write directly with readers. If enough of you support the book by pledging for it in advance, we produce a beautifully bound special subscribers edition and distribute a regular edition and e-book wherever books are sold, in shops and online.

This new way of publishing is actually a very old idea (Samuel Johnson funded his dictionary this way). Were just using the internet to build each writer a network of patrons. Here, at the back of this book, youll find the names of all the people who made it happen.

Publishing in this way means readers are no longer just passive consumers of the books they buy, and authors are free to write the books they really want. They get a much fairer return too half the profits their books generate, rather than a tiny percentage of the cover price.

If youre not yet a subscriber, we hope that youll want to join our publishing revolution and have your name listed in one of our books in the future. To get you started, here is a 5 discount on your first pledge. Just visit unbound.com, make your pledge and type RUBYPORT in the promo code box when you check out.

Introduction

I n the late 1990s I worked for Oddbins, a once mighty and now rather reduced firm of British wine merchants. We were paid little, but instead given a thorough education in wine (so thorough that some employees had to go to rehab). After a long days work and even longer evenings tasting, a favourite topic of discussion was which wine-producing country could we not do without. The most popular was, if I can remember correctly, France, though seeing this was the late 1990s and the company we worked for had made its reputation pioneering New World wines, some said Australia. Sometimes we even narrowed it down to a specific region that would produce our desert island wines. I always used to say sherry because I thought it made me sound sophisticated.

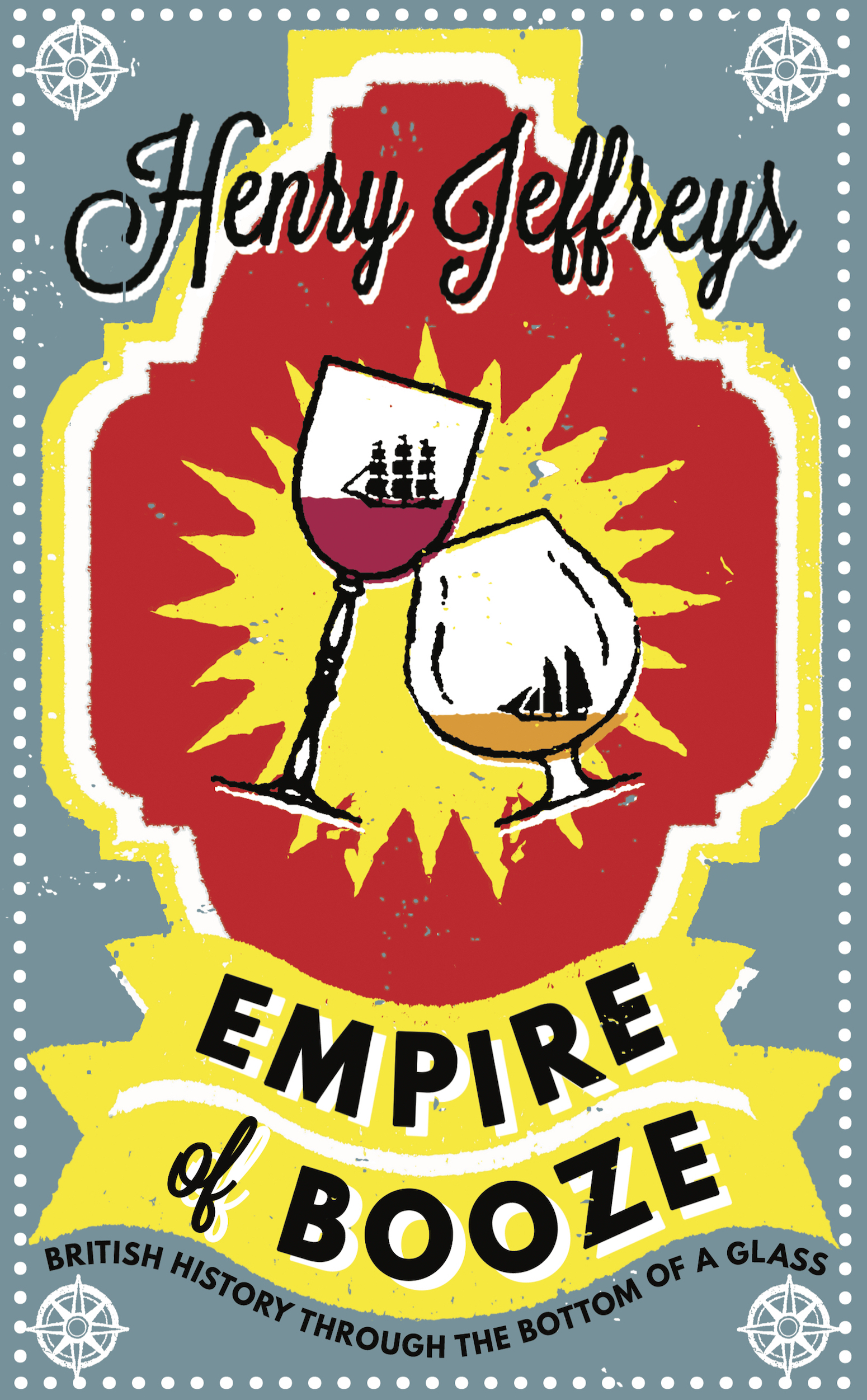

Later on in life, though, I realised Id missed a trick because the country with the greatest influence on wine and drink in general wasnt France, Germany or even Australia, it was Britain. Without the British influence, few of our favourite wines would even be in existence. This might sound like patriotic nonsense, that Ive had too much port to drink, but think about it. Champagne? The technology for making sparkling wine came from England and the taste for a bone-dry wine also came from these shores. Without Britain, champagne would have been flat and sweet. Port? Well, the names on the bottles are a clue, Taylors, Churchills, Smith Woodhouse. Claret? Bordeaux as a wine region was founded under English rule and, as a modern wine, was sold by British merchants. Rum? Beer? Whisky? They all owe something, if not everything, to Britain.

Of course, regions such as Champagne and Bordeaux would have created wine no matter who lay across the channel from them. But would they have become the paradigms of excellence to be admired and imitated the world over? Where the British role was key was in taking a local product, exploiting it and selling it globally. Almost all the worlds classic drinks such as gin, whisky, rum, madeira, sherry, claret, champagne and port became known in this way. Their success inspired imitators: there is a direct connection between the bottle of Chilean Cabernet you buy in the supermarket and the traditional English love for claret. The drinks the world enjoys today are, though often in mutated form, the drinks the British loved.

How did this small island exert such an influence on drinking habits across the world? The British do have a special relationship with alcohol. The climate might have something to do with that. Its often cold, damp and grey, but not so cold that all you want from a drink is oblivion like the Russians do with vodka, the Swedes with schnapps and the Mongolians with fermented mares milk. The British, in contrast, have a whole smorgasbord of drinks to make lifes realities a bit more bearable. Even in hot climes, or rather especially in hot climes, the British turn to drink. As Captain Thomas Walduck wrote in 1710: The first thing the English did was set up a tavern or drinking house be it the most remote parts of ye world or amongst the most Barbarous Indians.

Grapes have been grown in England since Roman times particularly by monastic orders. A combination of Henry VIIIs dissolution of the monasteries and a change in climate known as the Little Ice Age, which drastically lowered temperatures between the 16th and 19th centuries, meant that large-scale viticulture died out in England. Cereal crops were used to make beer and later whisky and gin, and apples to make cider. In order to drink wine, a drink that was ingrained in the culture of the ruling classes as well as essential for Christian communion, the people of the British Isles had to look abroad. Until Englands defeat by France at the Battle of Castillon in 1452, these wines would have come from the English territory of Bordeaux. For over 300 years, much of France was part of England including Bordeaux after the marriage of Eleanor of Aquitaine to Henry II in 1152. Due to its proximity to England and the easily navigable rivers of the Garonne and Dordogne, the south-west of France was planted with vines and the wines they created became a staple export over the Channel. It was the English thirst that drove demand for these wines. When Aquitaine was lost to France there wasnt an immediate problem. The wine trade with Bordeaux continued once it was in French hands, but further wars with France, and the resulting punitive duties on French goods, meant that new sources of wine had to be found. To this end, Englands handy geographical positioning combined with a native ingenuity. Sometimes this ingenuity took the form of plain thievery as when Drake stole over 1 million litres of sherry in a raid on Cadiz, but it was merchants in nearby Jerez who pointed the way for how things might be arranged in the future. This small colony of British traders would become the model for communities all over the world making money from alcohol. Trade, rather than piracy, would secure England and later Britain the drink she craved.

Britain was well placed to be wine merchant to the world. With the discovery of America, European trade shifted west. Furthermore by the 17th century Western nations were able to trade directly with the East without having to go through intermediaries. Prominent trading nations such as Venice, which had controlled the spice trade and the Mediterranean wine trade, became irrelevant. With Atlantic coasts and a great seafaring tradition Spain and Portugal were well placed too, but they had home-grown drink industries to protect. Their colonies were forbidden from commercialising their products. Englands and later Britains colonies were founded by private companies and were self-governing, whereas Spanish and Portuguese colonial ventures were subject to central control. The Dutch operated in a similar way to the English and they initially controlled a large slice of trade particularly with the East and the French wine trade. Englands rise to a great mercantile power was based on copying the Dutch: the development of the London Stock Exchange, and most importantly the Royal Navy. Through naval might England was able to first challenge and then sideline the Dutch. Unlike England, relatively safe behind the Channel and protected by the Royal Navy, The United Provinces were vulnerable to France which in the 17th century developed into the Continental superpower.