All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Random House, an imprint and division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

R ANDOM H OUSE and the H OUSE colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

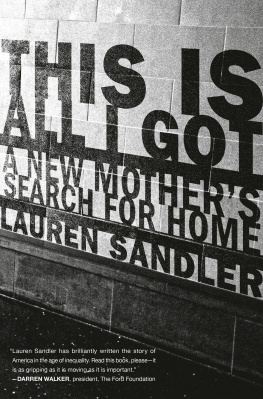

Names: Sandler, Lauren, author.

Title: This is all I got: a new mothers search for home / by Lauren Sandler.

Description: First edition. | New York: Random House, [2020]

Identifiers: LCCN 2019045309 (print) | LCCN 2019045310 (ebook) | ISBN 9780399589959 (hardback) | ISBN 9780399589966 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Homeless womenNew York (State)New York. | HomelessnessNew York (State)New York.

INTRODUCTION

I met Camila in 2015 at a shelter in Brooklyn, as spring was melting into summer. I would know her for much longer than a year, but this story is of the first twelve months, in which she fought to build a life of basic stability for herself and the baby who was about to be born.

With finishing-school posture, she walked into the weekly evening meeting for shelter residents in a fresh white blouse and a pair of twill short-shorts, slim but for her pregnant belly. She didnt look like she needed to be there, or thats what one of the new mothers in the room muttered to no one in particular. Camila took a seat, surveying the room, and began to advise another pregnant resident on maternity patients rights and natural birthing techniques. She was generous with a conspiratorial glance, maintaining just enough snap in her neck to remind the world she was Dominican, a constant portrait of double consciousness. But no matter how tall she carried herself, her feet remained anchored in a place she didnt want to be. She was born into struggle and deeply tethered there.

What set her apart? Was it her charisma? Her slightly preppy style? The world couldnt see her as someone who belonged in a shelter. Lets be straight: No one belongs in a shelter. Name any clich about fated futility, they all apply to the individual experience of managing poverty in America. But Camilas caseworkers would tell you that theyd never seen anyone as knowledgeable about the system in which she was stranded. They marveled at how she kept policy and dates and addresses and caseworkers names in her head like a savant, as she navigated waiting rooms and obtuse paperwork in her search for affordable housing, in her securing of public assistance, in her endeavors to establish legal paternity and procure child support, in her efforts to stay in school.

Camila held my eye contact as I explained to the group of women in the room that, if they were willing, I wanted to know their stories, to witness their lives. Some of them shrugged. Some of them shook their heads. Some nodded, open to the invitation, if skeptical. But Camila sat up even taller and folded her long fingers over the baby-blue purse resting on her lap. I could feel a light switch on and, with it, her mind revving, her thoughts lurching forward as she composed herself. Her cheeks, pale for Dominican skin, flushed slightly, like heat was building inside her. She waited politely for me to finish and for others in the room to speak. She set her jaw through the awkward silence that followed. And then, perched on the edge of her seat, her sandals firmly on the floor, Camila spoke. She said she had a story to tell.

As I came to learn, she had grown up mainly in apartments in Queens paid for by her mothers Section 8 housing voucher, back when a single mother could count on such support. No more. Her father had never lived in any of those apartments; he had his own life, and plenty of other kids, most of them with their own single mothers. Her mom had three other children of her own, too, and each had a different father, one more absent than the next. Camilas unfinished college years offered a succession of dorms at first, and once she got pregnant, a succession of shelters.

Here she was now, weeks before giving birth, making plans to stay off welfare and finish her degree in criminal justice. From that first meeting, I sensed that she was a woman who was hell-bent on propelling herself out of this shelter, away from the circumstances of her past, toward something solid, ambitious. And as I came to experience her, within and beyond her story, one thing was clear to me: If Camila couldnt use her wits and persistence to make the system work for her, no one could.

I was at the shelter where Camila was temporarily living because I wanted to witness and understand how deepening inequality is lived in America, and particularly in New York, a city that gets richer as the poor get poorer. This city is a fun-house mirror of national inequality, displaying class differences in their most exaggerated forms. At the shelter, I met women whose backgrounds varied but who all had nowhere to go when they showed up with their bags, and nowhere to go when they packed them once it was time to leave.

I first moved to the city in 1992, when homelessness was considered a national crisis. The night I unpacked my bags, 23,482 people slept in the citys public shelters. By the evening I met Camila in 2015, that number had ballooned to over sixty thousand people in the citys mainstream shelters, where in total, that year, over 127,000 people spent at least a night. That year, thousands more were housed in specialized shelters for domestic violence survivors, homeless youth, or people with HIV/AIDS. And thousands more, housed in hotel rooms or dilapidated apartments awaiting an eligibility determination for Temporary Housing Assistance, were denied ongoing aid. On the streets, in parks, on subway trains, over sidewalk vents, thousands more tried to find comfort on a strip of cardboard, a bag stuffed with whatever could be carried or scrounged.

A crisis of far greater magnitude is growing.

We see men, mostly, their stench pushing passengers to the other side of the train car or sitting on the edge of the sidewalk behind a cardboard sign. That man continues to be the emblem of homelessness and has been for decades. But theres a much larger homeless population in the city, an invisible one. One carefully made up, often headed to work or school, clustered down at the other end of the subway car with everyone else, avoiding that man in a greasy parka on a summers day.

Homeless: What word more obliterates the nuances and trials of complicated relationships, of ambitions, of plans? It means failure rather than perseverance; homelessness as an end, even at a young age. But the homelessness crisis is a single lens in the kaleidoscope of American povertymore specifically the catastrophe of urban American poverty, and even more specifically the poverty of women in urban America. The story of every person who has found themselves homeless, or in a place of serious housing instability, is individual, and yet each story is its own keyhole view of this countrys deepest flaws: the vanishing safety net, the scourge of housing inequality, the yoke of which family youre born into, the stubbornness of entrenched racism, and the burdens that women are forced to carry utterly alone.