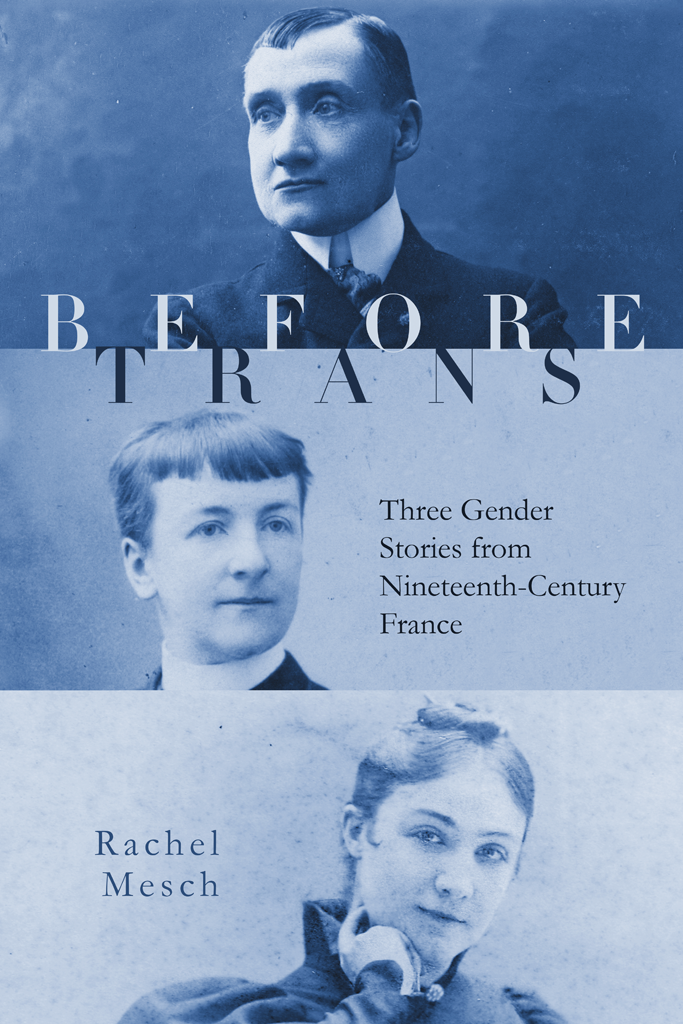

Rachel Mesch - Before Trans: Three Gender Stories from Nineteenth-Century France

Here you can read online Rachel Mesch - Before Trans: Three Gender Stories from Nineteenth-Century France full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2020, publisher: Stanford University Press, genre: Science fiction. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Before Trans: Three Gender Stories from Nineteenth-Century France

- Author:

- Publisher:Stanford University Press

- Genre:

- Year:2020

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Before Trans: Three Gender Stories from Nineteenth-Century France: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Before Trans: Three Gender Stories from Nineteenth-Century France" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Rachel Mesch: author's other books

Who wrote Before Trans: Three Gender Stories from Nineteenth-Century France? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Before Trans: Three Gender Stories from Nineteenth-Century France — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Before Trans: Three Gender Stories from Nineteenth-Century France" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Before Trans

Three Gender Stories from Nineteenth-Century France

RACHEL MESCH

STANFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS

Stanford, California

STANFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS

Stanford, California

2020 by the Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University.

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system without the prior written permission of Stanford University Press.

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free, archival-quality paper

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Names: Mesch, Rachel, author.

Title: Before trans : three gender stories from nineteenth-century France / Rachel Mesch.

Description: Stanford, California : Stanford University Press, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references and index. |

Identifiers: LCCN 2019040801 (print) | LCCN 2019040802 (ebook) | ISBN 9781503606739 (cloth) | ISBN 9781503612358 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Dieulafoy, Jane, 1851-1916. | Rachilde, 1860-1953. | Montifaud, Marc de, 18451912. | Transgender menFranceBiography. | Authors, French19th centuryBiography. | Gender identityFranceHistory19th century. | LCGFT: Biographies.

Classification: LCC HQ77.7 .M47 2020 (print) | LCC HQ77.7 (ebook) | DDC 306.76/8092 [B]dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019040801

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019040802

Cover design: Kevin Barrett Kane

Cover photos: Eugne Pirou / Bibliothque Marguerite Durand / Roger-Viollet

Typeset by Kevin Barrett Kane in 10/14.4 Minion Pro

Contents

INTRODUCTION

JANE DIEULAFOY MIGHT BE the most famous French person you have never heard of. In 1882, Dieulafoy and her husband, Marcel, a civil engineer and architecture enthusiast, left their comfortable home in the southern city of Toulouse to travel the unpaved roads and mountain paths of Baghdad and Turkey all the way to Persia, in what is modern-day Iran. They hoped to excavate the ancient city of Susa, which British explorer William K. Loftus had located decades earlier but failed to unearth. What they found exceeded their wildest expectations: extensive palaces buried underneath the sandy, rock-strewn hills, forgotten by time and nature. After two government-sponsored missions, the couple finally returned to France in 1886 with forty tons of artifacts from the royal homes of Darius and Artaxerxes. Resettled in Paris, they were celebrated with the opening of the Salle Dieulafoy at the Louvre, leading to record-breaking crowds for the museums new Department of Oriental Antiquities. Jane and Marcel Dieulafoy were a veritable fin-de-sicle power couple: they lectured about town, hosted an exclusive salon where they staged theatrical performances, hobnobbed with Prime Minister Raymond Poincar, and were regularly invited to President Flix Faures receptions.

All the while, the staunchly Catholic Dieulafoy went about in the most stylish mens suits.

She was one of only a handful of women to take this measure.

Jane Dieulafoy found a way to express her gender in a way that, to all appearances, made her comfortable and confident. But there were signs that, as she lived this unconventional life, she puzzled over who she was. She kept a notebook filled with clippings containing any mention of gender-crossing or pants permits, from current events, social commentary, or fiction. When her own name appeared in these accounts, it was underlined with a blue pencil.

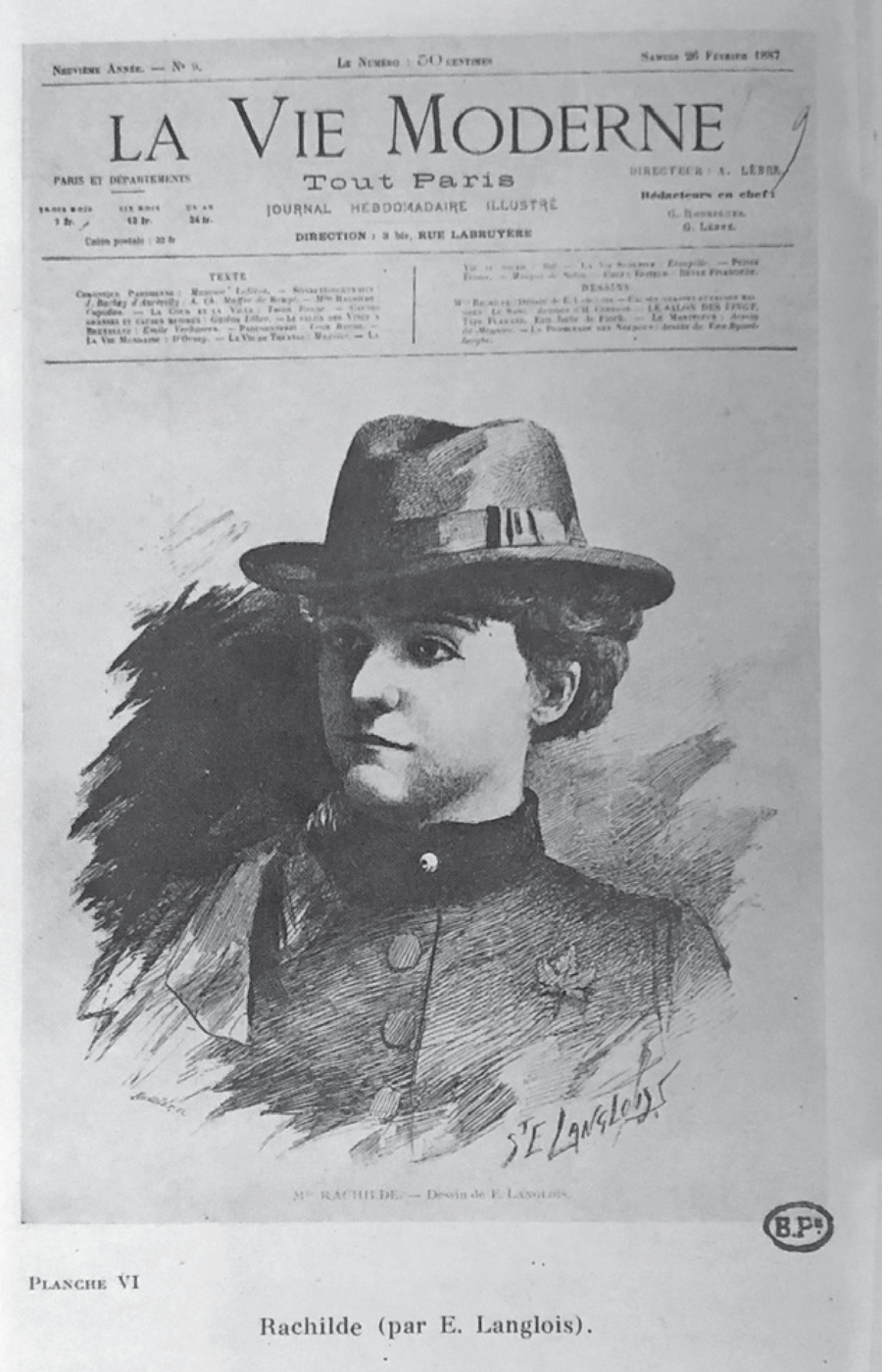

The name Rachilde may have also appeared in those pages, for she too had secured the pants permit at around the same time as Dieulafoy; born Marguerite Eymery, she had abandoned her rural home for Paris upon turning twenty-one in 1881. Taking the name of a Swedish nobleman whom she claimed to have channeled during a family sance, she found her way to the bohemian literary scene, eventually appearing at balls and cafs dressed in mens clothing. She had cut off her hair, stopped powdering her face, and began wearing bigger shoes as well.

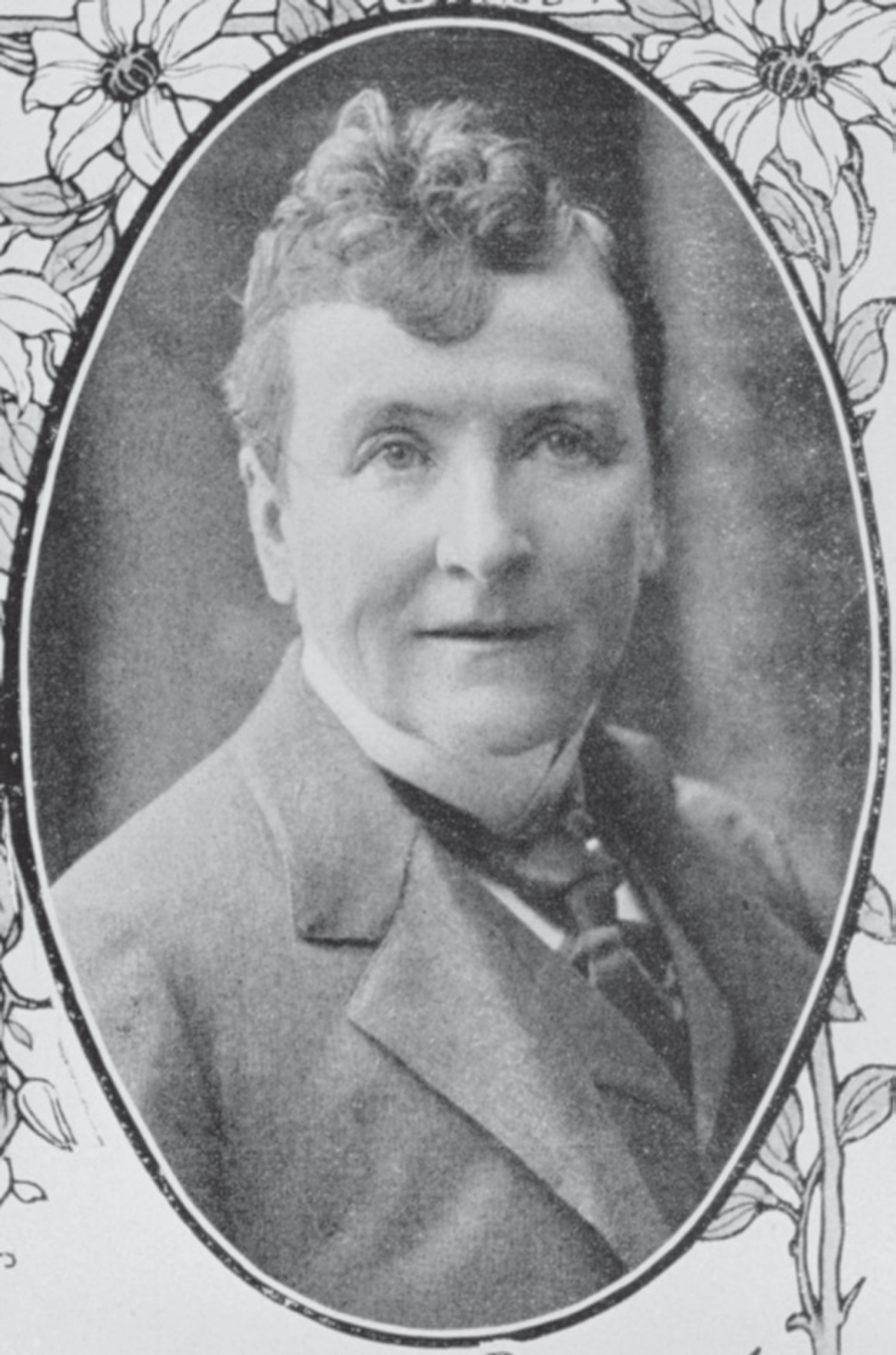

FIGURE 1. Jane Dieulafoy around 1900.

Source: Roger-Viollet. Reprinted with permission.

While Dieulafoy was digging up ruins in Persia, Rachilde released the decadent novel Monsieur Vnus with an enthusiastic Belgian publisher in 1884. The book earned her a hefty fine and a prison sentence in Brussels for pornographywhich she avoided by staying in Pariswhile also making her the sweetheart of the Parisian literary circuit. Unlike Dieulafoy, Rachilde seemed to embrace her identity as a rebel, even to cultivate it as a reputation, while steering clear of any identification with women writers or feminism. Her calling card read, Rachilde, Man of Letters.

But at the same time as she was building a reputation for wild antics, Rachilde felt deeply vulnerable and struggled for stability. In 1889 she surprised those who had come to think of her as an eccentric rebel by marrying the writer Alfred Vallette, choosing intellectual affinity and friendship over romantic inclination. At that point, she put her pants away and began working with Vallette to revive the famed literary journal the Mercure de France, becoming one of the most influential critics of the time as its chief book reviewer. Still, Rachilde continued to rail against the confines of her sex in fiction and plays that pressed hard against gender norms and conventional sexual categories. In her writing, Rachilde imagined her avatars alternately as a monster, a hysteric, an animal, a werewolf, a man.

In Dieulafoys notebook, another name appears next to her own with striking frequency: Marc de Montifaud, the name by which the writer christened Marie-Amlie Chartroule de Montifaud was best known. She, too, had received official permission to wear pants. Like Dieulafoy, she wore tailored mens suits and a mans haircut for much of her life. Rachilde had noticed her as well. In her short volume Why I Am Not a Feminist (1928), she mentions Montifaudmisspelling her name as Montifautalongside Dieulafoy as another of the women on French soil who dressed in mens clothing like herself during the 1880s.

Montifaud began her career as an art critic, and her work in that domain has recently been recognized for its personal, materialist vision, one that distinguishes itself from the conventions of the academy. But it was not Montifauds essays that made headlines in her day. She published dozens of anticlerical tales for which she was incessantlyand disproportionatelypursued by the French censors, some of whom were enraged that the writer they had assumed was a man was not. In 1877 Montifaud was charged with offense to public decency and sentenced to prison. (She would serve her time in an asylum instead.) The legal thrashing did not stop her from continuing to write. Despite repeated death threats, an attempted poisoning, and set-ups meant to prove her sexual impropriety, she continued to churn out controversial historical works, in addition to works of fiction that mocked the political forces out to get her. In some of these writings, Montifaud celebrated historical figures who had been persecuted for their difference or simply misunderstood, including the Abb de Choisy, one of the gender-crossers of whom Dieulafoy had also written a historical account.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Before Trans: Three Gender Stories from Nineteenth-Century France»

Look at similar books to Before Trans: Three Gender Stories from Nineteenth-Century France. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Before Trans: Three Gender Stories from Nineteenth-Century France and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.